THREE GRAVES:

THE NILE EXPEDITION - BATTLE OF KIRBEKAN, SUDAN, 1885

Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Homan Eyre, 1st South Staffordshire Regiment

Lichfield Cathedral

General William Earle

St. George's Hall, Liverpool

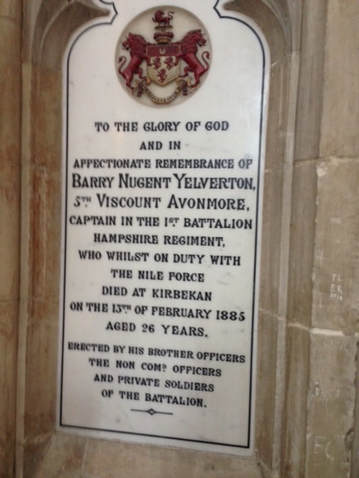

Captain Barry Nugget Yelverton, 1st Battalion Hampshire Regiment

Winchester Cathedral

I understand the hero-worship that surrounded, and still surrounds, General Gordon of Khartoum, but I cannot say I approve of it. Yes, he had done admirable things in the past, and yes, he was a man of principle and integrity, and I accept that he followed what he regarded as the chivalrous course by staying in Khartoum. I would still argue that his decision to remain was reckless.

One of the fundamentals of any army is that orders are issued and obeyed. The orders may be crass or idiotic, they may be misguided or ambiguous, but they should in the end be obeyed. If you do not want to obey orders, do not join an army (always assuming you have been given a choice, and in 1885 neither pressgangs nor conscription existed). There is some argument about the actual orders Gordon received, whether he was to act as an observer and report back, or whether he was to evacuate the Egyptian force and civilians, but he was definitely not ordered to take command of the city and prepare it for a siege. That was his choice, and through that choice scores of British troops were condemned to death in the desert.

Not that they would have seen it that way. Gladstone’s government in London may have been very reluctant to send an expedition to Khartoum to relieve Gordon, but the popular feeling, evinced in the media and in the public mood, was that one should be sent. That would not have been an unpopular decision in Egypt either. Khartoum had been effectively abandoned, and even though it was an Egyptian possession, not a British one, there was a clear feeling of humiliation, and a desire for revenge that motivated the wish to get to the Sudanese capital. Shame that desire could not instantly overcome the logistics.

The only feasible way to get large numbers of troops and supplies to Khartoum was by going up the Nile, negotiating the infamous cataracts on the way. The logistics took so long to organise that the relief forces did not set off until September, 1884, by which time Gordon had been besieged by the Mahdi’s forces for six months. The need for urgency was so obvious that two separate forces were dispatched; the River Column under Liverpool-born-and-raised General William Earle, and a Desert Column, mounted on camels, under Sir Hubert Stewart. The latter was intended to travel light and more quickly, but the supplies failed to keep pace and the column was forced to give up and meet up with the River Column. All this took time, and while they were creeping forward Khartoum fell, with Gordon’s head being presented, impaled on a sword, to the Mahdi. Apparently he was not amused.

With Gordon dead and Khartoum fallen the Column had no real purpose left, but the decision was taken to keep moving upriver with the aim of taking the river port of Berber to maintain a presence in the region. On February 9th, 1885, the force reached Kirbekan, on the Nile bend, which was commanded by three hills occupied by the Mahdists. They would have to be cleared before a further advance. This makes clear sense. There was no way Earle could leave a large hostile force in his rear, threatening the Column’s vital supply route. So it was that the River Column fought its only major action of the campaign.

Earle had initially planned a frontal assault on the closest hill, his men wearing red uniforms as Earle followed Gordon’s belief that the red coats would affect the enemy’s morale. Reconnaissance, however, found a deep wadi winding round behind the hills, and Earle was persuaded to use it to outflank the Mahdists and attack from the rear. Irish-born Colonel Philip Homan Eyre was to lead his men of the South Staffordshire Regiment, supported by companies of The Black Watch commanded by Australian Captain Bob Coveny.

As covering fire from the front diverted the defenders’ attention Eyre, after an hour’s march, was in position to move along their rear when they were spotted. Ordering the rest of his command to continue the advance Eyre led two of his companies up the slope, but the enemy fire was too accurate, Eyre was killed, and his surviving men pinned down amidst the dusty rocks.

Meanwhile the remaining Staffordshires and the Black Watch were committed to the planned assault. With the defenders diverted by Eyre’s men the Black Watch took their hill, and then the remaining Staffordshires charged in support of their trapped comrades and completed the victory. General Earle lived to witness it, but not to enjoy it, as a shot from a concealed marksman killed him as his troops were securing the tops.

Three commanders were buried that evening beside a lone tree on the bank of the Nile, the desert stretching sway from them. Beside Earle and Eyre (both in their fifties) the Sydney-born, Stoneyhurst-educated Bob Coveny, in his thirties, had also been killed. The son of a wealthy Sydney merchant he could have entered his father’s business, but instead chose the military career which led to his isolated grave.

Earle was also the son of a merchant. His father, the wonderfully-named Hardman Earle, was a Liverpool businessman who had been created a baronet for his wealth and his public works, but his son William had, like Bob Coveny, followed the military path. He had seen action in the Crimea before marrying and fathering two daughters. One of those daughters, Grace, married into the aristocratic Villiers family, lived into the 1960s, and gave Earle grandchildren that he would never see. His statue stands in splendour outside Liverpool’s St. George’s Hall.

Philip Homan Eyre was from a family of Galway landowners (providing Sheriffs and MPs, so presumably not too innocent in the Famine), although he was born in Borrisokane in County Tipperary. His parents, Richard and Eleanor, were probably not too well off (or disagreed with his choice of an army career), for he did not go into officer training, nor have a commission bought for him, as the 1851 Census locates him in Chester Castle as a Private in the 38th Foot, the South Staffordshire Regiment that he would die at the head of at Kirbekan.

He married Lucy Clarke at Taunton in 1873, and by 1877, by which time he was a Major, having been promoted through the ranks after seeing service in both the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny, he was the father of two children, both born in Bideford. One of those children, his son Hastings, became a major in his father’s battalion. Philip’s great-grandson, Richard Eyre, is the noted theatre, opera, film and t.v. director who won a BAFTA Best Director award in 1988 for his film about another far-flung conflict, Tumbledown. Philip is commemorated on a brass plaque, which is very difficult to photograph, in Lichfield Cathedral.

On other casualty should be mentioned, if only to symbolise all those men who died on active service, but not in conflict. I don’t know whether he fought in the battle, or whether he was already too ill, but on February 13th the 5th Viscount Avonmore, Captain Barry Nugent Yelverton of the 1st Hampshire Regiment, Instructor of Musketry, died of enteric fever at Kirbekan. He was 26, and has a striking plaque in Winchester Cathedral.

And what did all lead to? Having been successful at Kirbekan the River Column prepared to move on to take Berber. However, new orders arrived. With the Desert Column in too poor a state to continue as a fighting group the overall force was too weak in numbers to face an extended campaign had never been intended, and the supply route was deemed far too extended and vulnerable. Colonel Henry Brackenbury, Earle’s second-in-command, was ordered to return to Egypt, leaving three graves under a tree by the riverbank.

One of the fundamentals of any army is that orders are issued and obeyed. The orders may be crass or idiotic, they may be misguided or ambiguous, but they should in the end be obeyed. If you do not want to obey orders, do not join an army (always assuming you have been given a choice, and in 1885 neither pressgangs nor conscription existed). There is some argument about the actual orders Gordon received, whether he was to act as an observer and report back, or whether he was to evacuate the Egyptian force and civilians, but he was definitely not ordered to take command of the city and prepare it for a siege. That was his choice, and through that choice scores of British troops were condemned to death in the desert.

Not that they would have seen it that way. Gladstone’s government in London may have been very reluctant to send an expedition to Khartoum to relieve Gordon, but the popular feeling, evinced in the media and in the public mood, was that one should be sent. That would not have been an unpopular decision in Egypt either. Khartoum had been effectively abandoned, and even though it was an Egyptian possession, not a British one, there was a clear feeling of humiliation, and a desire for revenge that motivated the wish to get to the Sudanese capital. Shame that desire could not instantly overcome the logistics.

The only feasible way to get large numbers of troops and supplies to Khartoum was by going up the Nile, negotiating the infamous cataracts on the way. The logistics took so long to organise that the relief forces did not set off until September, 1884, by which time Gordon had been besieged by the Mahdi’s forces for six months. The need for urgency was so obvious that two separate forces were dispatched; the River Column under Liverpool-born-and-raised General William Earle, and a Desert Column, mounted on camels, under Sir Hubert Stewart. The latter was intended to travel light and more quickly, but the supplies failed to keep pace and the column was forced to give up and meet up with the River Column. All this took time, and while they were creeping forward Khartoum fell, with Gordon’s head being presented, impaled on a sword, to the Mahdi. Apparently he was not amused.

With Gordon dead and Khartoum fallen the Column had no real purpose left, but the decision was taken to keep moving upriver with the aim of taking the river port of Berber to maintain a presence in the region. On February 9th, 1885, the force reached Kirbekan, on the Nile bend, which was commanded by three hills occupied by the Mahdists. They would have to be cleared before a further advance. This makes clear sense. There was no way Earle could leave a large hostile force in his rear, threatening the Column’s vital supply route. So it was that the River Column fought its only major action of the campaign.

Earle had initially planned a frontal assault on the closest hill, his men wearing red uniforms as Earle followed Gordon’s belief that the red coats would affect the enemy’s morale. Reconnaissance, however, found a deep wadi winding round behind the hills, and Earle was persuaded to use it to outflank the Mahdists and attack from the rear. Irish-born Colonel Philip Homan Eyre was to lead his men of the South Staffordshire Regiment, supported by companies of The Black Watch commanded by Australian Captain Bob Coveny.

As covering fire from the front diverted the defenders’ attention Eyre, after an hour’s march, was in position to move along their rear when they were spotted. Ordering the rest of his command to continue the advance Eyre led two of his companies up the slope, but the enemy fire was too accurate, Eyre was killed, and his surviving men pinned down amidst the dusty rocks.

Meanwhile the remaining Staffordshires and the Black Watch were committed to the planned assault. With the defenders diverted by Eyre’s men the Black Watch took their hill, and then the remaining Staffordshires charged in support of their trapped comrades and completed the victory. General Earle lived to witness it, but not to enjoy it, as a shot from a concealed marksman killed him as his troops were securing the tops.

Three commanders were buried that evening beside a lone tree on the bank of the Nile, the desert stretching sway from them. Beside Earle and Eyre (both in their fifties) the Sydney-born, Stoneyhurst-educated Bob Coveny, in his thirties, had also been killed. The son of a wealthy Sydney merchant he could have entered his father’s business, but instead chose the military career which led to his isolated grave.

Earle was also the son of a merchant. His father, the wonderfully-named Hardman Earle, was a Liverpool businessman who had been created a baronet for his wealth and his public works, but his son William had, like Bob Coveny, followed the military path. He had seen action in the Crimea before marrying and fathering two daughters. One of those daughters, Grace, married into the aristocratic Villiers family, lived into the 1960s, and gave Earle grandchildren that he would never see. His statue stands in splendour outside Liverpool’s St. George’s Hall.

Philip Homan Eyre was from a family of Galway landowners (providing Sheriffs and MPs, so presumably not too innocent in the Famine), although he was born in Borrisokane in County Tipperary. His parents, Richard and Eleanor, were probably not too well off (or disagreed with his choice of an army career), for he did not go into officer training, nor have a commission bought for him, as the 1851 Census locates him in Chester Castle as a Private in the 38th Foot, the South Staffordshire Regiment that he would die at the head of at Kirbekan.

He married Lucy Clarke at Taunton in 1873, and by 1877, by which time he was a Major, having been promoted through the ranks after seeing service in both the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny, he was the father of two children, both born in Bideford. One of those children, his son Hastings, became a major in his father’s battalion. Philip’s great-grandson, Richard Eyre, is the noted theatre, opera, film and t.v. director who won a BAFTA Best Director award in 1988 for his film about another far-flung conflict, Tumbledown. Philip is commemorated on a brass plaque, which is very difficult to photograph, in Lichfield Cathedral.

On other casualty should be mentioned, if only to symbolise all those men who died on active service, but not in conflict. I don’t know whether he fought in the battle, or whether he was already too ill, but on February 13th the 5th Viscount Avonmore, Captain Barry Nugent Yelverton of the 1st Hampshire Regiment, Instructor of Musketry, died of enteric fever at Kirbekan. He was 26, and has a striking plaque in Winchester Cathedral.

And what did all lead to? Having been successful at Kirbekan the River Column prepared to move on to take Berber. However, new orders arrived. With the Desert Column in too poor a state to continue as a fighting group the overall force was too weak in numbers to face an extended campaign had never been intended, and the supply route was deemed far too extended and vulnerable. Colonel Henry Brackenbury, Earle’s second-in-command, was ordered to return to Egypt, leaving three graves under a tree by the riverbank.

|

To the glory of God and in loving memory of Philip Woman Eyre, Lieut. Colonel 1st S. Staffordshire Regiment, who fell whilst leading his men at the battle of Kirbekan Feb. 10th 1885 having served 33 years in the Regiment. This brass is erected by his sorrowing widow. 'Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord. They may rest from their labours and their works do follow them'.

|

|

Sources

Pictures

Kirbekan, Northern Sudan - Scott D. Haddow, on Flickr.com

Portrait of LTC Philip Woman Eyre - submitted by wildgoose to www.findagrave.com

Statue of William Earle outside St. George's Hall, Liverpool - by Man vyi

Captain Robert Coveny - from www.victorianwars.com

Plaque to Captain Yelverton - original photo by Kate Dewhirst

Military

The London Gazette, January 9th 1853

Army Lists 1839-1915 - from www.digital.nls.uk

Wikipedia

www.victorianwars.com - a fascinating forum site

Pharaoh - David Gibbins, Hachette UK, 2013

Battle Honours of the British Army, C. B. Norman, 1911, republished by Andrews UK, 2012

Modern Egypt - Evelyn Baring, 1908, republished Cambridge University Press, 2010

The Colonial Wars Sourcebook - Philip J. Haythornthwaite, BCA, London, 1995

Blood-Red Desert Sand, the British Invasion of Egypt and The Sudan, 1882-1898 - Michael Barthorp, Cassell, London, 1984 (originally published as 'War on the Nile')

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.thepeerage.com

www.liverpoolhiddenhistory.co.uk

Pictures

Kirbekan, Northern Sudan - Scott D. Haddow, on Flickr.com

Portrait of LTC Philip Woman Eyre - submitted by wildgoose to www.findagrave.com

Statue of William Earle outside St. George's Hall, Liverpool - by Man vyi

Captain Robert Coveny - from www.victorianwars.com

Plaque to Captain Yelverton - original photo by Kate Dewhirst

Military

The London Gazette, January 9th 1853

Army Lists 1839-1915 - from www.digital.nls.uk

Wikipedia

www.victorianwars.com - a fascinating forum site

Pharaoh - David Gibbins, Hachette UK, 2013

Battle Honours of the British Army, C. B. Norman, 1911, republished by Andrews UK, 2012

Modern Egypt - Evelyn Baring, 1908, republished Cambridge University Press, 2010

The Colonial Wars Sourcebook - Philip J. Haythornthwaite, BCA, London, 1995

Blood-Red Desert Sand, the British Invasion of Egypt and The Sudan, 1882-1898 - Michael Barthorp, Cassell, London, 1984 (originally published as 'War on the Nile')

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.thepeerage.com

www.liverpoolhiddenhistory.co.uk

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2018