Battle of Atbara, Sudan, 1898

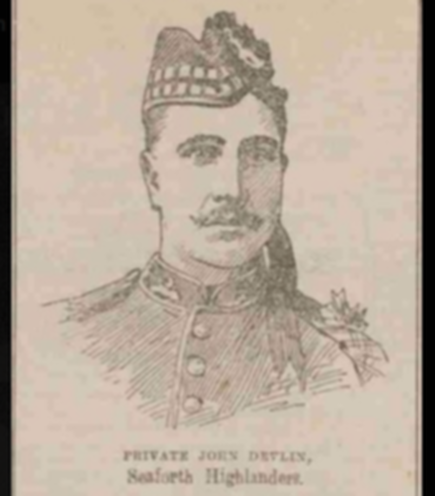

Private John Devlin, Seaforth Highlanders

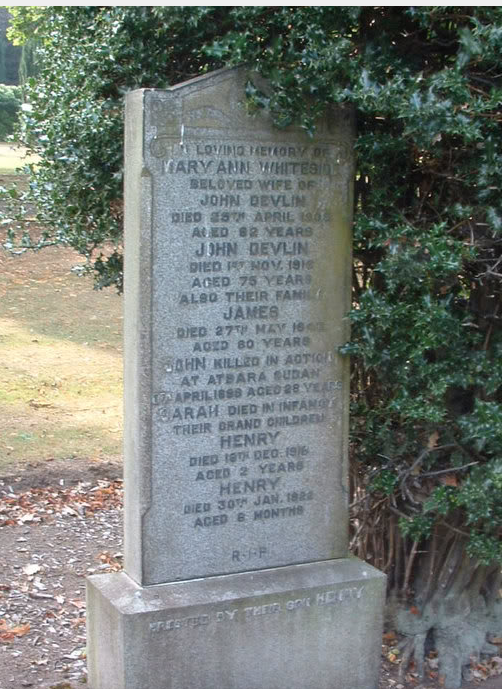

Camelon Cemetery, Falkirk

2nd Lieutenant Paul Alexander Gore, Seaforth Highlanders,

St. Peter's, Copdock, Suffolk

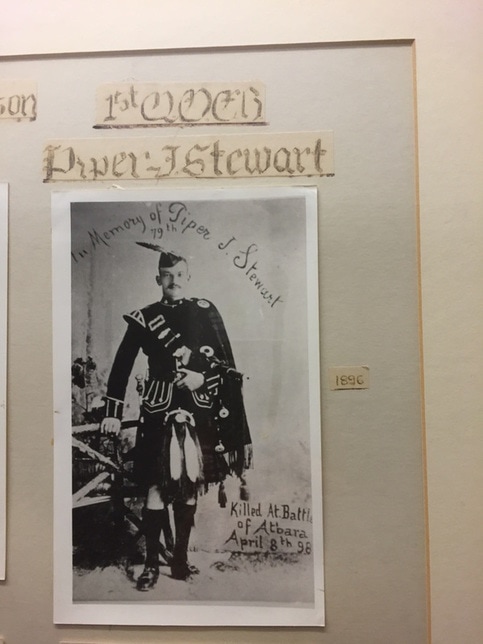

Piper J. Stewart, Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders

Achiltibuei Piping College, Highlands

Photo of Piper James Stewart on the corridor wall of the Achiltibuie Piping School

Photo of Piper James Stewart on the corridor wall of the Achiltibuie Piping School

Can we connect an urban cemetery in Falkirk, a Suffolk parish church, a café on the Coigach coast of North-west Scotland and an Ethiopian market town? Obviously the answer is going to be in the affirmative, although there would not be a link had an Italian army not been defeated at the Battle of Adwa in northern Ethiopia in March 1896.

The Italian defeat prompted the Mahdist regime in Sudan to threaten the Italian-occupied port of Kassala on the Gash River in eastern Sudan. As Kassala had previously been Egyptian the British/Egyptian powers wanted it back, and certainly did not want it falling into the hands of the Mahdists. The British-Egyptian forces, therefore, invaded Sudan from the north, spurred on also by their fear of French infiltration into the regions of the Upper Nile. If that is not complicated enough, throw in a soupçon of revenge, as the leader of the British forces, General Kitchener, was eager to avenge the death of his former commander, General Gordon, who had been killed by the Mahdists in Khartoum in 1885.

Kitchener entered Sudan in March 1896, and had early successes, but the strategy was to be slow but sure. Communications were the primary focus, with time and care spent constructing two railways south from Wadi Haifa, with extra and strengthened fortified camps to guard them. Over the following eighteen months the slow advance continued, punctuated by the occasional capture of Mahdist garrisons along the routes of the railway, and along the Nile.

Eventually, early in 1898, Kitchener was ready, advancing down the Nile on gunboats, supplied by rail. The leader of the Mahdist government, the Khalifa, had to act.

Three hundred miles north of Khartoum lies Atbara, at the confluence of the eponymous river and the Nile. Kitchener had established a fort at the junction of the rivers, and the Khalifa ordered one of his generals, Emir Mahmud Ahmed, north to engage the British. However, Mahmud did not engage immediately, pausing instead on March 20th 1898 twenty miles south of Kitchener's fort, and erecting his own fortified camp, with trenches and zarebas, a barriers of thornbushes.

After preparing for the expected attack Kitchener realised that Mahmud was reluctant to fight, and so he decided to take the initiative. On April 7th he ordered a night march across the gravelly desert which allowed his forces to be in a position to attack at dawn the next day. The British-Egyptian force had about ten and a half thousand troops, against the Mahdists' fifteen thousand, which included five thousand cavalry. However, Kitchener's troops were all armed with modern rifles, while their enemy were mostly (though not all) armed with spears and swords.

As the British soldiers waited in the grey light of a desert dawn, one wonders whether their thoughts drifted homeward. Did Private John Devlin, of the Seaforth Highlanders, picture the terraced streets of the Scottish steel town he had left behind? Born in Falkirk in 1868, he was the second son of John and Mary Ann (née Whiteside), who had moved to Central Scotland from Coalisland in Ulster following their marriage in 1862. John senior had come over as an agricultural labourer, then worked as a carter and general labourer. John junior, a successful local footballer (one non-competitive appearance for Falkirk), had worked as an iron moulder before enlisting.

One of Devlin's officers, Lieutenant Paul Alexander Gore, offered a contrast. Born in Mussorie, Bengal, in 1877, he was the son of a future Surveyor-General of India, and the grandson of a Church of England clergyman. His father was St. George Corbet Gore, born in New South wales, and his mother the India-born Elizabeth Mackinnon. He was educated in England, living in Devon with his paternal grandparents (one born in Ireland, the other in Guernsey), and when the time came he joined a Scottish regiment.

Alongside the Seaforths were the Cameron Highlanders, including F Company and their piper, James Stewart. He was a native of Kincraig in Invernessshire, in the Highlands, but was living in the Perthshire village of Dull when he enlisted in 1892. The regiment were stationed in Egypt and it was to there that he was posted after his training.

At dawn Kitchener's four artillery batteries opened fire on the Mahdist camp. The cannonade lasted for just over an hour, during which the Mahdist cavalry attempted an attack, only to driven back by the British Maxim guns. Once the artillery had ceased the infantry were ordered forward, with Sudanese and Egyptian troops to the right and in the centre, with the British contingent of Seaforth and Cameron Highlanders, supported by the 1st Royal Warwickshire and the 1st Lincolns, to the left.

Protected by the thick zareba the Mahdists poured a torrent of gunfire into the troops advancing up the gravel slope, with the Sudanese in the centre in particular experiencing heavy losses. On the left the Camerons were in front, with the Seaforths behind. Piper James Stewart led the advance, playing 'The March of the Cameron Men' despite the hail of bullets. We are told that he received seven shots to the body, playing on until he succumbed to the final bullet. As he fell the Camerons were close enough to the zareba for some of the troops to begin pulling it down, while others fired through the gaps created. Then through and over those gaps drove the Seaforths. One account tells of Sergeant-Major Mackay jumping the thorns only to encounter a spearman slashing at him while he was in mid-air. The spear ripped his kilt in two, but left him uninjured and he shot his assailant. It was minutes after that incident that Lieutenant Paul Gore was shot and killed. Of Private John Devlin we know only that he died in the assault, probably in the fierce hand-to-hand fighting that ensued, with no quarter given; in the trenches that lay behind the zareba more than two thousand Mahdist bodies lay at the close of the fighting. With them lay eighty British casualties, including Private Devlin, Lieutenant Gore and Piper Stewart.

Devlin is commemorated on the family gravestone in Falkirk's Camelon Cemetery. Gore has a plaque in the church of St. Peter's in Copdock, Suffolk, three miles south-west of Ipswich. Piper Stewart is misnamed Peter on the memorial cross in Kincraig, south of Aviemore on the old A9. His picture can be seen in the piping school and café at Achiltibuie on Scotland's Atlantic coast.

Sources

Pictures

Portrait of Piper James Stewart - author

Portrait of Private John Devlin - from the Falkirk Herald, featured on John Meffen's fascinating site, www.falkirk-football-history.co.uk

St. Peter's Church, Copdock - photo by Oxymoron, © CC BY-SA 2.0

The Italian defeat prompted the Mahdist regime in Sudan to threaten the Italian-occupied port of Kassala on the Gash River in eastern Sudan. As Kassala had previously been Egyptian the British/Egyptian powers wanted it back, and certainly did not want it falling into the hands of the Mahdists. The British-Egyptian forces, therefore, invaded Sudan from the north, spurred on also by their fear of French infiltration into the regions of the Upper Nile. If that is not complicated enough, throw in a soupçon of revenge, as the leader of the British forces, General Kitchener, was eager to avenge the death of his former commander, General Gordon, who had been killed by the Mahdists in Khartoum in 1885.

Kitchener entered Sudan in March 1896, and had early successes, but the strategy was to be slow but sure. Communications were the primary focus, with time and care spent constructing two railways south from Wadi Haifa, with extra and strengthened fortified camps to guard them. Over the following eighteen months the slow advance continued, punctuated by the occasional capture of Mahdist garrisons along the routes of the railway, and along the Nile.

Eventually, early in 1898, Kitchener was ready, advancing down the Nile on gunboats, supplied by rail. The leader of the Mahdist government, the Khalifa, had to act.

Three hundred miles north of Khartoum lies Atbara, at the confluence of the eponymous river and the Nile. Kitchener had established a fort at the junction of the rivers, and the Khalifa ordered one of his generals, Emir Mahmud Ahmed, north to engage the British. However, Mahmud did not engage immediately, pausing instead on March 20th 1898 twenty miles south of Kitchener's fort, and erecting his own fortified camp, with trenches and zarebas, a barriers of thornbushes.

After preparing for the expected attack Kitchener realised that Mahmud was reluctant to fight, and so he decided to take the initiative. On April 7th he ordered a night march across the gravelly desert which allowed his forces to be in a position to attack at dawn the next day. The British-Egyptian force had about ten and a half thousand troops, against the Mahdists' fifteen thousand, which included five thousand cavalry. However, Kitchener's troops were all armed with modern rifles, while their enemy were mostly (though not all) armed with spears and swords.

As the British soldiers waited in the grey light of a desert dawn, one wonders whether their thoughts drifted homeward. Did Private John Devlin, of the Seaforth Highlanders, picture the terraced streets of the Scottish steel town he had left behind? Born in Falkirk in 1868, he was the second son of John and Mary Ann (née Whiteside), who had moved to Central Scotland from Coalisland in Ulster following their marriage in 1862. John senior had come over as an agricultural labourer, then worked as a carter and general labourer. John junior, a successful local footballer (one non-competitive appearance for Falkirk), had worked as an iron moulder before enlisting.

One of Devlin's officers, Lieutenant Paul Alexander Gore, offered a contrast. Born in Mussorie, Bengal, in 1877, he was the son of a future Surveyor-General of India, and the grandson of a Church of England clergyman. His father was St. George Corbet Gore, born in New South wales, and his mother the India-born Elizabeth Mackinnon. He was educated in England, living in Devon with his paternal grandparents (one born in Ireland, the other in Guernsey), and when the time came he joined a Scottish regiment.

Alongside the Seaforths were the Cameron Highlanders, including F Company and their piper, James Stewart. He was a native of Kincraig in Invernessshire, in the Highlands, but was living in the Perthshire village of Dull when he enlisted in 1892. The regiment were stationed in Egypt and it was to there that he was posted after his training.

At dawn Kitchener's four artillery batteries opened fire on the Mahdist camp. The cannonade lasted for just over an hour, during which the Mahdist cavalry attempted an attack, only to driven back by the British Maxim guns. Once the artillery had ceased the infantry were ordered forward, with Sudanese and Egyptian troops to the right and in the centre, with the British contingent of Seaforth and Cameron Highlanders, supported by the 1st Royal Warwickshire and the 1st Lincolns, to the left.

Protected by the thick zareba the Mahdists poured a torrent of gunfire into the troops advancing up the gravel slope, with the Sudanese in the centre in particular experiencing heavy losses. On the left the Camerons were in front, with the Seaforths behind. Piper James Stewart led the advance, playing 'The March of the Cameron Men' despite the hail of bullets. We are told that he received seven shots to the body, playing on until he succumbed to the final bullet. As he fell the Camerons were close enough to the zareba for some of the troops to begin pulling it down, while others fired through the gaps created. Then through and over those gaps drove the Seaforths. One account tells of Sergeant-Major Mackay jumping the thorns only to encounter a spearman slashing at him while he was in mid-air. The spear ripped his kilt in two, but left him uninjured and he shot his assailant. It was minutes after that incident that Lieutenant Paul Gore was shot and killed. Of Private John Devlin we know only that he died in the assault, probably in the fierce hand-to-hand fighting that ensued, with no quarter given; in the trenches that lay behind the zareba more than two thousand Mahdist bodies lay at the close of the fighting. With them lay eighty British casualties, including Private Devlin, Lieutenant Gore and Piper Stewart.

Devlin is commemorated on the family gravestone in Falkirk's Camelon Cemetery. Gore has a plaque in the church of St. Peter's in Copdock, Suffolk, three miles south-west of Ipswich. Piper Stewart is misnamed Peter on the memorial cross in Kincraig, south of Aviemore on the old A9. His picture can be seen in the piping school and café at Achiltibuie on Scotland's Atlantic coast.

Sources

Pictures

Portrait of Piper James Stewart - author

Portrait of Private John Devlin - from the Falkirk Herald, featured on John Meffen's fascinating site, www.falkirk-football-history.co.uk

St. Peter's Church, Copdock - photo by Oxymoron, © CC BY-SA 2.0