Farewell, Queen Charlotte - The British-American War, Lake Erie, USA/Canada, 1813

Captain Robert Finnis, HMS Queen Charlotte

St. Leonard's, Hythe, Kent

The conventional view of Britain's 19th Century wars is that they are either the huge conflicts (Napoleon, Crimea, Boer) or that they are conducted against valiant foe who, armed with only spears and bows, eventually succumb to superior fire-power. However, the War against America, which lasted from June 1812 through to 1815, was different. It is often regarded as merely a sub-conflict of the Napoleonic Wars, but the enemy were certainly armed with more than shields and spears, and Captain Robert Finnis of the sloop Queen Charlotte, would be one of its victims.

Whatever the virtues of the men featured in these stories, it has to be said that the wars in which they fought were rarely fought for admirable purposes (I did say rarely; there are exceptions). Most seem to involve money and trade, land, pride and loss of face.The American War manages to include all of them.

War was actually declared by the Americans. The USA was neutral in the British war against France, and thus felt entitled to trade with whoever it wished. The British disagreed, wanting, understandably, to deprive the French of money and resources by blockading its ports. The Americans protested, the British ignored the protests. Motive number one. Motive two involved the USA's western expansion, threatening British territory and spheres of influence in Canada and its southern environs. The British were reluctant to get involved in direct conflict, but not so reluctant that they wouldn't arms the native tribes who, in defending their land, were also a barrier to the western expansion. Motive number three lay in the simmering American resentment of the activities of the Royal Navy, who on occasion had stopped American ships, searched them for British deserters (no-one asked whether the British deserters had been press-ganged in the first place), and taken those identified as such back onto the British ship. One affair in 1807, the memory of which still lingered five years later, involved HMS Leopard intercepting USS Chesapeake and removing four of its crew, one of whom was subsequently hung. Bearing in mind that the two countries had already fought one war within living memory, it is easy to see that such an affront as the Chesapeake affair would not be readily forgiven. Such resentments can be long-lived; I have met people who never buy Japanese goods because of what Japan did in World War Two, and George Macdonald Fraser, the creator of the Flashman novels, opposed Britain's membership of the EU because he said he would never trust the Germans, who had started three wars in the preceding hundred years (he did, conveniently, not notice that Germany and France's membership of the EU had led to the most peaceful half-century in Western European history).

The British seemed to be in control of Lake Erie. They had six ships based at Detroit, whereas the Americans only had one, and that was captured. However, they were very short of sailors, with a hundred of the three hundred men available being infantrymen. They were also short of cannons and guns, and with the Americans in control of the Niagara River and Lake Ontario they were struggling to replenish what they had. In contrast the Americans had no ships, but they did have men, and they did have communications allowing them to bring in supplies and resources. They established a base at Presque Isle on the south-eastern shore of the lake, a bay protected by a large sandbank. It was here that they began constructing ships, safe in the knowledge that the British could not get over the sandbank to interrupt them. When they had ten ships constructed and fitted, it was time for action.

Some readers may ask how, if the British could not get in, the Americans could get out? The smaller ships could sail out, while the larger ones, having been stripped of their heavy cannons, were piggy-backed on barges out into the open water. The British had been blockading the bay, but they were driven away by a combination of bad weather and failing supplies, allowing the Americans, under Commander Oliver Perry, the opportunity to get out and anchor in open water.

On September 10th, 1813, the British fleet, under Commander Robert Barclay, appeared, initially with the wind in its favour. However, the wind shifted, and allowed the Americans to attack. The first shot was fired at quarter to twelve, and one of the first casualties of the battle, killed in the first broadside, was Captain Robert Finnis of HMS Queen Charlotte. He was a native of Hythe in Kent, and had a reputation of being a resourceful and brave officer, earned in 1801 when he was seventeen, when, as an ensign serving on HMS Beaulieu, he led a cutting-out operation that stole the French ship La Chevrette from Camaret Bay in Brittany. His qualities were not allowed to shine on Lake Erie, unfortunately., and his death presaged the British defeat. Outnumbered and outgunned the British were always going to struggle, and so it proved, even though they did manage to turn the American flagship, the Lawrence, into a smouldering wreck. By three o'clock all their ships had either been crippled or had surrendered, with Barclay severely injured (he would lose a leg to add to his already missing arm) and most of his officers dead or wounded. The Americans had control of Lake Erie.

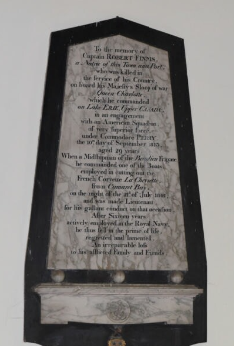

Robert Finnis has a memorial in the church of St. Leonard's in Hythe, but his body was buried, with those of six other officers, British and American, on South Bass Island. On the centenary of the battle the bodies were disinterred and placed in the crypt below a new monument, the Perry's Victory and International Peace Monument, where they still lie today.

Whatever the virtues of the men featured in these stories, it has to be said that the wars in which they fought were rarely fought for admirable purposes (I did say rarely; there are exceptions). Most seem to involve money and trade, land, pride and loss of face.The American War manages to include all of them.

War was actually declared by the Americans. The USA was neutral in the British war against France, and thus felt entitled to trade with whoever it wished. The British disagreed, wanting, understandably, to deprive the French of money and resources by blockading its ports. The Americans protested, the British ignored the protests. Motive number one. Motive two involved the USA's western expansion, threatening British territory and spheres of influence in Canada and its southern environs. The British were reluctant to get involved in direct conflict, but not so reluctant that they wouldn't arms the native tribes who, in defending their land, were also a barrier to the western expansion. Motive number three lay in the simmering American resentment of the activities of the Royal Navy, who on occasion had stopped American ships, searched them for British deserters (no-one asked whether the British deserters had been press-ganged in the first place), and taken those identified as such back onto the British ship. One affair in 1807, the memory of which still lingered five years later, involved HMS Leopard intercepting USS Chesapeake and removing four of its crew, one of whom was subsequently hung. Bearing in mind that the two countries had already fought one war within living memory, it is easy to see that such an affront as the Chesapeake affair would not be readily forgiven. Such resentments can be long-lived; I have met people who never buy Japanese goods because of what Japan did in World War Two, and George Macdonald Fraser, the creator of the Flashman novels, opposed Britain's membership of the EU because he said he would never trust the Germans, who had started three wars in the preceding hundred years (he did, conveniently, not notice that Germany and France's membership of the EU had led to the most peaceful half-century in Western European history).

The British seemed to be in control of Lake Erie. They had six ships based at Detroit, whereas the Americans only had one, and that was captured. However, they were very short of sailors, with a hundred of the three hundred men available being infantrymen. They were also short of cannons and guns, and with the Americans in control of the Niagara River and Lake Ontario they were struggling to replenish what they had. In contrast the Americans had no ships, but they did have men, and they did have communications allowing them to bring in supplies and resources. They established a base at Presque Isle on the south-eastern shore of the lake, a bay protected by a large sandbank. It was here that they began constructing ships, safe in the knowledge that the British could not get over the sandbank to interrupt them. When they had ten ships constructed and fitted, it was time for action.

Some readers may ask how, if the British could not get in, the Americans could get out? The smaller ships could sail out, while the larger ones, having been stripped of their heavy cannons, were piggy-backed on barges out into the open water. The British had been blockading the bay, but they were driven away by a combination of bad weather and failing supplies, allowing the Americans, under Commander Oliver Perry, the opportunity to get out and anchor in open water.

On September 10th, 1813, the British fleet, under Commander Robert Barclay, appeared, initially with the wind in its favour. However, the wind shifted, and allowed the Americans to attack. The first shot was fired at quarter to twelve, and one of the first casualties of the battle, killed in the first broadside, was Captain Robert Finnis of HMS Queen Charlotte. He was a native of Hythe in Kent, and had a reputation of being a resourceful and brave officer, earned in 1801 when he was seventeen, when, as an ensign serving on HMS Beaulieu, he led a cutting-out operation that stole the French ship La Chevrette from Camaret Bay in Brittany. His qualities were not allowed to shine on Lake Erie, unfortunately., and his death presaged the British defeat. Outnumbered and outgunned the British were always going to struggle, and so it proved, even though they did manage to turn the American flagship, the Lawrence, into a smouldering wreck. By three o'clock all their ships had either been crippled or had surrendered, with Barclay severely injured (he would lose a leg to add to his already missing arm) and most of his officers dead or wounded. The Americans had control of Lake Erie.

Robert Finnis has a memorial in the church of St. Leonard's in Hythe, but his body was buried, with those of six other officers, British and American, on South Bass Island. On the centenary of the battle the bodies were disinterred and placed in the crypt below a new monument, the Perry's Victory and International Peace Monument, where they still lie today.

Sources

Photos

Memorial to Captain Robert Finnis - photo by Les Featherstone, posted on the War Memorials Register on iwm.org.uk

Perry's Victory and International Peace Monument , taken from the harbour area of Put-In Bay - photo by Alvintrusty

Genealogy and military

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.hythehistoryblog.wordpress.com

www.ancestrypaths.com/tag/battle-of-lake-erie

www.history.goerie.com

Photos

Memorial to Captain Robert Finnis - photo by Les Featherstone, posted on the War Memorials Register on iwm.org.uk

Perry's Victory and International Peace Monument , taken from the harbour area of Put-In Bay - photo by Alvintrusty

Genealogy and military

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.hythehistoryblog.wordpress.com

www.ancestrypaths.com/tag/battle-of-lake-erie

www.history.goerie.com