THE FRANKLIN COPPERMINE EXPEDITION, NORTH-EAST CANADA, 1819-22

Lieutenant Robert Hood, Royal Navy

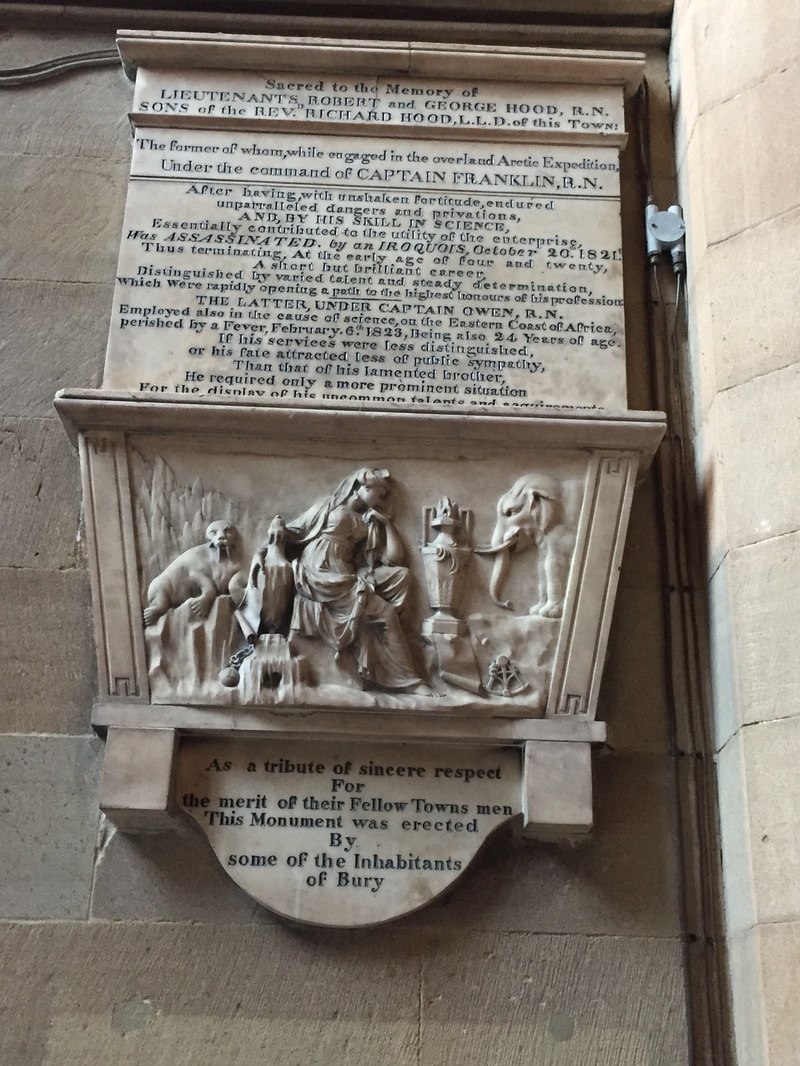

St. Mary the Virgin, Bury, Lancashire

The Man

Many people will now be familiar with the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, the parish church of Bury, in Lancashire, as it was where the funeral service of Drummer Lee Rigby was held in July 2013. If any of those attending had looked around the church before or after the service they may well have seen the memorial for another young man who died in the service of his country, albeit nearly two hundred years earlier.

In the early decades of the 19th Century the scholarly vicar of Bury was the Reverend Richard Hood, and one of his sons was Robert, who in 1809, at the age of twelve, joined the Royal Navy. In 1811 he was made Midshipman, and saw action in a number of places, including the attack on Algiers, before passing his Lieutenancy exams in 1816, with special commendations for his drawing skills. Unfortunately, passing the exam did not mean promotion, as the Navy had retrenched in the post-Napoleonic peace and many naval officers were placed on half-pay, forced to wait for any opportunity that may present itself.

The Background

Robert Hood’s chance came in 1819, when he was appointed Midshipman on a Royal Navy expedition to search for the North-West Passage, a fabled route around the north of Canada that would, in theory, provide shorter and swifter journeys to the Orient. The plans on this occasion involved a sea-borne expedition from the east and a land-based expedition from the west. Hood was appointed to the latter, with responsibility as artist and map-maker, under the command of Lieutenant John Franklin. There were three other naval men on the team: Dr. John Richardson, doctor and naturalist; Midshipman George Back, surveyor; and Able-Seaman John Hepburn, who had previous experience in Arctic conditions, having been on Franklin’s earlier Spitsbergen expedition. The party’s aim was to explore the coastline east from the mouth of the Coppermine River, on what is now called Coronation Gulf, hopefully meeting up with Captain Parry’s sea-based force.

The Journey Begins

In late August 1819 the party arrived at York Factory, on the south-western shore of Hudson’s Bay. They were supposed to get support, in terms of manpower and supplies, from two mercantile companies, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West Company, but the promised men failed to appear, so when the party headed west, for Cumberland House, a trading post on the Saskatchewan River, they were forced to leave some supplies behind.

Hood and Richardson overwintered at Cumberland House, commenting on the bitter cold in their journals, while the other three moved over 500 miles further north to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca. When Hood and Richardson joined them in the spring they moved on to Fort Providence, on the Great Slave Lake, where Franklin at last managed to engage some interpreters and boatmen (known as voyageurs), and some Indian guides. They were still short of supplies, but Franklin decided they would be able to subsist on what they had, augmented with game they could shoot and food they could get from local tribes, although the local Yellowknife tribe chief, Akaitcho, warned them that there was not much food available further north.

In August 1820 the party moved out to establish a base camp, which they called Fort Enterprise, close to the Coppermine River. From this camp, in which the party would see out the winter, they could reconnoitre the route up the Coppermine to the coast, and establish supplies for the journey. It was not to be a happy station.

The main problem was, as had been the case throughout, a lack of supplies. Although they were collecting for the expected exploration, there certainly would not be sufficient to leave behind for their return, and so they were relying on a pledge from Akaicho that he would deposit a store of food for them while they were away. Unsurprisingly the voyageurs were sceptical about these arrangements, and often seemed close to mutiny. To make matters worse, a dispute broke out within the naval party itself. Back and Hood were both attracted to the same Indian girl, whom they called Greenstockings, and their rivalry became so intense that they arranged a duel, which was only prevented by Hepburn having the foresight to remove the ammunition for their pistols. Franklin then sent Back to Fort Chipewyan to elicit more supplies, which left Hood free to continue his courtship of Greenstockings and leave her pregnant.

In late August 1819 the party arrived at York Factory, on the south-western shore of Hudson’s Bay. They were supposed to get support, in terms of manpower and supplies, from two mercantile companies, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West Company, but the promised men failed to appear, so when the party headed west, for Cumberland House, a trading post on the Saskatchewan River, they were forced to leave some supplies behind.

Hood and Richardson overwintered at Cumberland House, commenting on the bitter cold in their journals, while the other three moved over 500 miles further north to Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca. When Hood and Richardson joined them in the spring they moved on to Fort Providence, on the Great Slave Lake, where Franklin at last managed to engage some interpreters and boatmen (known as voyageurs), and some Indian guides. They were still short of supplies, but Franklin decided they would be able to subsist on what they had, augmented with game they could shoot and food they could get from local tribes, although the local Yellowknife tribe chief, Akaitcho, warned them that there was not much food available further north.

In August 1820 the party moved out to establish a base camp, which they called Fort Enterprise, close to the Coppermine River. From this camp, in which the party would see out the winter, they could reconnoitre the route up the Coppermine to the coast, and establish supplies for the journey. It was not to be a happy station.

The main problem was, as had been the case throughout, a lack of supplies. Although they were collecting for the expected exploration, there certainly would not be sufficient to leave behind for their return, and so they were relying on a pledge from Akaicho that he would deposit a store of food for them while they were away. Unsurprisingly the voyageurs were sceptical about these arrangements, and often seemed close to mutiny. To make matters worse, a dispute broke out within the naval party itself. Back and Hood were both attracted to the same Indian girl, whom they called Greenstockings, and their rivalry became so intense that they arranged a duel, which was only prevented by Hepburn having the foresight to remove the ammunition for their pistols. Franklin then sent Back to Fort Chipewyan to elicit more supplies, which left Hood free to continue his courtship of Greenstockings and leave her pregnant.

The Coppermine

On the 4th June, 1821, the expedition set off north up the Coppermine, still short of supplies, but confident of being able to trade with the local Inuit tribes. Twenty-five men set out: the 5 naval personnel; 14 voyageurs; a North-West Company representative; and four Yellowknife Indian guides.

On July 14th they came across an Inuit camp, but their hopes of establishing a trading relationship proved fruitless. The Inuit fled when they saw the party, and from what was left in the camp it was evident that they were short of food themselves. It was at this point that the Yellowknife guides and the Company man turned back, leaving the rest to continue with the purpose of the expedition.

On the 18th July they reached the mouth of the Coppermine and started to travel east by canoe along the coast. Progress was slow in rough seas, and on 18th August they decided to turn back, at a spot on the Kent Peninsula they named Point Turnaround. A look on the map at the peninsula explains the reasoning. The southern side is a bay 100 miles long; to have to head west again after their travails must have been very demoralising.

Franklin now made the decision to head cross-country rather than retrace their route along the coast. The canoes had been damaged and he thought they would be unlikely to survive the journey, and with winter setting in they could not afford to lose time. So they set off, carrying the canoes, across an uncharted snow-covered region known as The Barren Grounds; it sounds like a chapter in Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones.

On the 4th June, 1821, the expedition set off north up the Coppermine, still short of supplies, but confident of being able to trade with the local Inuit tribes. Twenty-five men set out: the 5 naval personnel; 14 voyageurs; a North-West Company representative; and four Yellowknife Indian guides.

On July 14th they came across an Inuit camp, but their hopes of establishing a trading relationship proved fruitless. The Inuit fled when they saw the party, and from what was left in the camp it was evident that they were short of food themselves. It was at this point that the Yellowknife guides and the Company man turned back, leaving the rest to continue with the purpose of the expedition.

On the 18th July they reached the mouth of the Coppermine and started to travel east by canoe along the coast. Progress was slow in rough seas, and on 18th August they decided to turn back, at a spot on the Kent Peninsula they named Point Turnaround. A look on the map at the peninsula explains the reasoning. The southern side is a bay 100 miles long; to have to head west again after their travails must have been very demoralising.

Franklin now made the decision to head cross-country rather than retrace their route along the coast. The canoes had been damaged and he thought they would be unlikely to survive the journey, and with winter setting in they could not afford to lose time. So they set off, carrying the canoes, across an uncharted snow-covered region known as The Barren Grounds; it sounds like a chapter in Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones.

The Barren Grounds

By September 7th their supplies were exhausted, and they were existing on foraging, with the main food being an edible lichen called rock-tripe, which gave a number of the group, including Hood, diarrhoea. The voyageurs were mutinous, and discarded the canoes and fishing gear, but stayed with the party as in this unknown landscape they did not know where they were. On the 26th they finally reached the Coppermine River – but without the abandoned canoes they could not cross, and without the discarded nets they could not catch fish. Richardson tried to swim the river, but failed and had to be dragged back. It was after this that the first voyageur was lost, as Juninus ran away, and was never seen again.

Fortunately another voyageur, Pierre St. Germain, had the vision and skills to manufacture a makeshift canoe, and on October 4th they all managed to cross the river, leaving them an estimated week’s march away from Fort Enterprise.

However, the party was now struggling. On the 6th two voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, could go no further and were abandoned. The next day, with Hood and Richardson exhausted, Franklin decided to split the party into three. Back and three voyageurs, the strongest of the party, would forge ahead, and then return with supplies. Hepburn would stay with Richardson and Hood, and await rescue. Franklin and the remaining voyageurs would follow Back’s group, although within a few hours four of the voyageurs would decide to turn back and wait with Richardson’s group, although only one of them, Michel Terohaute, actually arrived.

On the 10th Back’s group reached Fort Enterprise, only to find to their dismay that the expected supplies were not there. Having left a message for Franklin, they decided to forge on for Fort Providence. Franklin’s group arrived on the 12th, and settled down to wait.

Meanwhile, back at Richardson’s camp, Terohaute went hunting and returned with some meat, a feat he repeated over the next few days. Eventually it began to dawn on the explorers that the meat was possibly human, which would explain the missing three voyageurs with whom Terohaute had parted from Franklin. On October 20th, with Hood in a poor condition, Richardson and Hepburn decided to go foraging. While they were out of the camp they heard a shot, and returned to find Terohaute standing with his rifle over Hood’s body – the boy from Bury had been shot through the head. According to Richardson’s account Terohaute claimed it was an accident, and, armed and aggressive as he was, the other two felt they couldn’t do anything about what was clearly murder.

Three days later they finally acted. Terohaute went out ‘hunting’ again, and when he returned Richardson shot him. It’s not really clear why it took Richardson so long given that he believed Terohaute to be a cannibal and Hood’s murderer, and Terohaute has to have slept sometimes. After the killing Richardson and Hepburn set out for Fort Enterprise, reaching it on October 29th. When they arrived there they were dismayed to find a scene of despair: the floorboards had been ripped up for fuel, the hides that had hung on the walls to keep in the warmth had been eaten, and only one man, the voyageur Peltier, had strength enough to rise to greet them. That strength was deceptive, as on November 1st both he and another voyageur, Salmandre, died.

Relief finally arrived on November 7th, when three of Akaicho’s tribe arrived with food, having met Back’s party on their way to Fort Providence. On 11th December the survivors reached Fort Providence themselves, to learn that Hood’s promotion to Lieutenant had finally been confirmed, just a couple of months too late.

By September 7th their supplies were exhausted, and they were existing on foraging, with the main food being an edible lichen called rock-tripe, which gave a number of the group, including Hood, diarrhoea. The voyageurs were mutinous, and discarded the canoes and fishing gear, but stayed with the party as in this unknown landscape they did not know where they were. On the 26th they finally reached the Coppermine River – but without the abandoned canoes they could not cross, and without the discarded nets they could not catch fish. Richardson tried to swim the river, but failed and had to be dragged back. It was after this that the first voyageur was lost, as Juninus ran away, and was never seen again.

Fortunately another voyageur, Pierre St. Germain, had the vision and skills to manufacture a makeshift canoe, and on October 4th they all managed to cross the river, leaving them an estimated week’s march away from Fort Enterprise.

However, the party was now struggling. On the 6th two voyageurs, Credit and Vaillant, could go no further and were abandoned. The next day, with Hood and Richardson exhausted, Franklin decided to split the party into three. Back and three voyageurs, the strongest of the party, would forge ahead, and then return with supplies. Hepburn would stay with Richardson and Hood, and await rescue. Franklin and the remaining voyageurs would follow Back’s group, although within a few hours four of the voyageurs would decide to turn back and wait with Richardson’s group, although only one of them, Michel Terohaute, actually arrived.

On the 10th Back’s group reached Fort Enterprise, only to find to their dismay that the expected supplies were not there. Having left a message for Franklin, they decided to forge on for Fort Providence. Franklin’s group arrived on the 12th, and settled down to wait.

Meanwhile, back at Richardson’s camp, Terohaute went hunting and returned with some meat, a feat he repeated over the next few days. Eventually it began to dawn on the explorers that the meat was possibly human, which would explain the missing three voyageurs with whom Terohaute had parted from Franklin. On October 20th, with Hood in a poor condition, Richardson and Hepburn decided to go foraging. While they were out of the camp they heard a shot, and returned to find Terohaute standing with his rifle over Hood’s body – the boy from Bury had been shot through the head. According to Richardson’s account Terohaute claimed it was an accident, and, armed and aggressive as he was, the other two felt they couldn’t do anything about what was clearly murder.

Three days later they finally acted. Terohaute went out ‘hunting’ again, and when he returned Richardson shot him. It’s not really clear why it took Richardson so long given that he believed Terohaute to be a cannibal and Hood’s murderer, and Terohaute has to have slept sometimes. After the killing Richardson and Hepburn set out for Fort Enterprise, reaching it on October 29th. When they arrived there they were dismayed to find a scene of despair: the floorboards had been ripped up for fuel, the hides that had hung on the walls to keep in the warmth had been eaten, and only one man, the voyageur Peltier, had strength enough to rise to greet them. That strength was deceptive, as on November 1st both he and another voyageur, Salmandre, died.

Relief finally arrived on November 7th, when three of Akaicho’s tribe arrived with food, having met Back’s party on their way to Fort Providence. On 11th December the survivors reached Fort Providence themselves, to learn that Hood’s promotion to Lieutenant had finally been confirmed, just a couple of months too late.

Afterwards

Sir John Franklin embarked on another three Arctic expeditions, and also spent time as Governor of Van Dieman’s Land, now Tasmania. He died during his Fourth Expedition in 1848, when he was over sixty, still searching for the North-West Passage. Two ships were lost and all one hundred and thirty crew died.

Sir John Richardson went on Franklin’s Second Expedition, and then spent his time as a doctor at the Royal Navy Hospital in Haslar and as a writer of Natural History books. He retired to Grasmere, and died there in 1865, being buried in the town’s St. Oswald’s Church.

Admiral Sir George Back went on Franklin’s Second Expedition, and then led a further two himself. He died in 1878, and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

John Hepburn was employed in a variety of posts, from being a warden at Haslar to being Superintendent of a convict institution in Tasmania, usually through Franklin’s good offices. He died in South Africa in 1864.

The man who was probably responsible for saving the survivors’ lives was Pierre St. Germain. If he had not built that makeshift canoe that enabled them to cross the Coppermine the chances are they would all have been stranded and starved. He continued to work as a translator for the Hudson’s Bay Company, before settling with his family to farm on the Red River in the 1830s. He died sometime in the 1840s.

Robert Hood’s remains were left in the wilderness, while the other four returned to Britain to be feted as heroes. At least he had a ground squirrel, a flower and a river named after him.

Sir John Franklin embarked on another three Arctic expeditions, and also spent time as Governor of Van Dieman’s Land, now Tasmania. He died during his Fourth Expedition in 1848, when he was over sixty, still searching for the North-West Passage. Two ships were lost and all one hundred and thirty crew died.

Sir John Richardson went on Franklin’s Second Expedition, and then spent his time as a doctor at the Royal Navy Hospital in Haslar and as a writer of Natural History books. He retired to Grasmere, and died there in 1865, being buried in the town’s St. Oswald’s Church.

Admiral Sir George Back went on Franklin’s Second Expedition, and then led a further two himself. He died in 1878, and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

John Hepburn was employed in a variety of posts, from being a warden at Haslar to being Superintendent of a convict institution in Tasmania, usually through Franklin’s good offices. He died in South Africa in 1864.

The man who was probably responsible for saving the survivors’ lives was Pierre St. Germain. If he had not built that makeshift canoe that enabled them to cross the Coppermine the chances are they would all have been stranded and starved. He continued to work as a translator for the Hudson’s Bay Company, before settling with his family to farm on the Red River in the 1830s. He died sometime in the 1840s.

Robert Hood’s remains were left in the wilderness, while the other four returned to Britain to be feted as heroes. At least he had a ground squirrel, a flower and a river named after him.

Sources

Photos

Church of St. Mary the Virgin - by David Ingham, from Wikimedia Commons

Preparing an Encampment on the Barren Grounds - engraving by Edward Finden from a painting by George Back, originally published in Franklin, John (1823). Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1819-22. London: John Murray - from Wikimedia Commons

Lieutenant John Franklin - by William Darby (1786-1847), engraved by James Thomson (1787-1850), from Library & Archives, Canada, Peter Winkworth Collection of Canadiana (ref. R9266-3037)

John Richardson, 1828 - painting by Thomas Phillips (1770-1845), engraved by Edward Finders (1791-1857), from The US national Library of Medicine (ref. B022270 Portraits)

George Back, 1833 - by William Brockedon (1787-1854), National Portrait Gallery, London

A Yellowknife hunter named Keskarrah (right) and his daughter (nicknamed "Greenstockings") - by Robert Hood, originally published in Franklin, John (1823). Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1819-22. London: John Murray - from Wikimedia Commons

Akaitcho, with his son - by Robert Hood, ibid.

Hilltop view of Kugluktuk - by Andrew Johnson, of Yellowknife, Canada ⓒ Creative Commons

Wilberforce Falls, Hood River, Nunavut, Canada - by Frances Auger

Military and Geneology

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hood_robert_6E.html

http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=2919&&PHPSESSID=ychzfqkvzape

http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic36-2-210.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coppermine_Expedition_of_1819–22

http://www.rmg.co.uk/explore

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Back

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Richardson_(naturalist)

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=4494

http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic39-4-370.pdf

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2015