Storming of Namtow, China, 1858

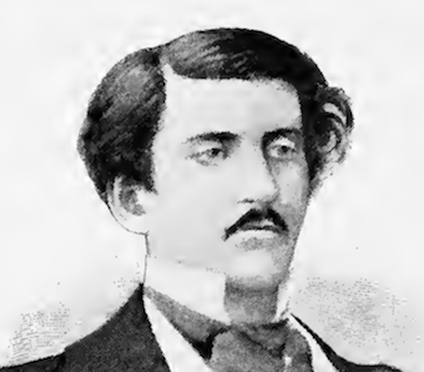

Captain William Francis Lambert, Royal Engineers

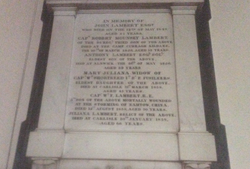

St. Michael's, Alnwick, Northumberland

Lieutenant Robert William Danvers, 10th Bengal Native Infantry

Queen's Chapel of the Savoy, London

Namtow (now Namtau) is a sub-district of Shenzhen in Guangdong province, China, on the mainland opposite Hong Kong, and had a population of just over a million in 2010, a number that has undoubtedly grown since then. In contrast Alnwick, the county town of Northumberland in north-east England, had just over 8,000 inhabitants in 2011, and yet these two disparate places were joined in 1858, when Captain William Francis Lambert, of the Royal Engineers, was attached to the 59th Foot, the 2nd Nottinghamshire Regiment, and joined in the attack on Namtow.

The Lamberts were, and presumably still are, a well-established Northumbrian family, and William’s branch was a successful professional one. They were landowners and lawyers and soldiers, with the latter having a strong Indian connection. William’s father, John, was one of the solicitors, living on Narrowgate in Alwick, and practicing in the town. His wife, Juliana, was a native of Carlisle, and she and John had six children. The girls, May and Cicely, married local landowners. Three of the boys – John, William and George – went into the military, while the eldest, Anthony, took the safer option and joined his father’s legal practice.

William, baptized in January 1828, went to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, where he excelled in Mathematics and Draughtsmanship, passing out top of his year in those disciplines. He must have travelled the world with the Royal Engineers, and must also have been a decent horseman, as he is recorded as having won The Montreal Grand Steeplechase on Broker in 1852. By 1858 he was in China, serving in the conflict known as The Second Opium War, and he was, presumably, pleased when the Treaty of Tientsin in June of that year seemed to have brought peace, with success for the western powers (not just European, also American, Russian and Japanese) and humiliation for China. Fundamentally it was all about trade, with the treaty opening up more ports to foreign traders, allowing them to use the rivers to trade inland, and granting the British a monopoly in the opium trade.

Namtow was a port, protected by a fort, on the eastern bank of the estuary of the Pearl (or Zhujiang) River, with a hinterland that provided much of Hong Kong’s workforce. Servants, merchants, shopkeepers and artisans all commuted regularly between the mainland and Hong Kong island. This factor became significant from the British point of view in the second week of July when those living on the mainland failed to return to Hong Kong, and those Chinese living on the island left. The belief was that this withdrawal of labour was the result of an order from the local Chinese authorities, and Hong Kong was faced with disaster, as all the island’s food supplies depended upon the mainland. Moreover it raised some bitter memories for the British.

Some eighteen months earlier, in late 1856, the Chinese governor in Canton had instructed all Chinese working for Europeans to return to their homes, on pain of death. The command cannot have been obeyed totally, as in January 1857 the colony was still being provided with bread baked by Chinese. Unfortunately for the European population one day’s baking was enhanced by the addition of arsenic to the dough. Fortunately for them it was so diluted in the process that no-one died immediately, although a number were permanently affected, including Maria, the wife of Sir John Bowring, Governor of Hong Kong. Bowring was a man of impeccable liberal credentials, a man who had supported reform in both Britain and Hong Kong, but the poisoned bread understandably soured him, and when the threat reappeared he was willing to take firm action.

By the third week of July 1858 most Chinese residents of Hong Kong had left the colony. No supplies were coming from the mainland, markets had no provisions, shops were closed, all Chinese merchants and shopkeepers had withdrawn, and European merchants were raising concerns about running their businesses without workers. An extraordinary meeting was held on the 29th July, and came to a resolution; the colony would act with force should the Chinese authorities not allow people back and resume supplies.

The districts from where the menaces emanate …… are threatened

with the retributive vengeance of the British Government

Over the following weeks the proclamation was delivered to the various Chinese towns around Hong Kong, although it must be assumed that by the 9th August, when the gunboat HMS Starling approached Namtow, every Chinese official within a hundred miles would have been aware of the resolution. The Starling was flying a “flag of truce”, but given that neither side trusted each other an inch it is not surprising that the Chinese in Namtow ignored the white flag and opened fire, forcing the ship to withdraw. In British eyes this was an insult and a humiliation. Retribution would have to be sought.

At nine in the morning on August 11th British forces landed in a suburb to the south-east of the city and advanced in two parallel lines. On the seaward road an advance party of a naval brigade under Captain Slight of HMS Sanspareil fought its way towards the fort, taking casualties from attacks down the intersecting streets. Further inland another force, mainly of the 59th Foot under Major Romer, advanced, pausing whenever shade was available, “the heat being fearful”. Royal Marines and the 12th Madras Native Infantry were kept in reserve.

By one o’clock troops were in position, the assault ladders were ready, and the attack began. Three ladders were laid and the first men up were the officers: Captain Slight, Commander Saumarez of HMS Cormorant and Captain William Francis Lambert. As all the British troops, including those in reserve, poured over after them the battle did not last long. By two o’clock the fort was in the attackers’ hands, and its destruction began. Both it and the surrounding city were razed, showing the Chinese that the British could not be treated with disdain.

What happened to William Lambert?

As he was climbing the ladder an altercation started behind him. A lascar seaman from the Cormorant and a soldier of the 59th jostled to be next up. As they struggled the seaman’s gun went off, and its bullet hit Lambert in the groin. He died the following day, never having even entered the fort, a rather sad and sordid footnote to a rather sad and sordid episode. Both sides could have avoided the fight, but honour had to be assuaged. Even Lambert’s death was the result of two men fighting for the privilege of being second up that ladder.

Ironically he was not the only officer to be a victim of friendly fire. Twenty-five year old Lieutenant Robert William Danvers of the 70th Bengal Native Infantry, who had been attached to the attacking force, was supervising the re-embarkation of the troops the day after the battle. All troops were ordered to discharge their muskets before going on board, as a result of which Danvers was shot through the body. Back home in London his parents placed a memorial in The Queen’s Chapel in The Savoy Hotel. His father was Clerk and Registrar to the Duchy of Lancaster, and both his brothers, Juland and James, went on to be senior civil servants, living to 1902 and 1919 respectively. If Robert had stuck with Theology he may have had a similarly long life, receiving honours and a good pension instead of a Hong Kong grave.

William Lambert’s two soldier brothers had differing lives. Captain John Lambert was killed the Battle of Sobraon in 1846, a victim of the First Sikh War. George Craster Lambert served in the Sikh wars and Burma, and on the North-west Frontier, eventually becoming Lieutenant-Colonel of the 101st regiment, the Royal Bengal Fusiliers. He retired as a Major-General to Bolton Hall, near Edlingham in Northumberland. The family's losses were not over however. George’s son, another John, was killed in the attack on Neuve Chapelle in October, 1914. The killing never seems to end.

The Lamberts were, and presumably still are, a well-established Northumbrian family, and William’s branch was a successful professional one. They were landowners and lawyers and soldiers, with the latter having a strong Indian connection. William’s father, John, was one of the solicitors, living on Narrowgate in Alwick, and practicing in the town. His wife, Juliana, was a native of Carlisle, and she and John had six children. The girls, May and Cicely, married local landowners. Three of the boys – John, William and George – went into the military, while the eldest, Anthony, took the safer option and joined his father’s legal practice.

William, baptized in January 1828, went to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, where he excelled in Mathematics and Draughtsmanship, passing out top of his year in those disciplines. He must have travelled the world with the Royal Engineers, and must also have been a decent horseman, as he is recorded as having won The Montreal Grand Steeplechase on Broker in 1852. By 1858 he was in China, serving in the conflict known as The Second Opium War, and he was, presumably, pleased when the Treaty of Tientsin in June of that year seemed to have brought peace, with success for the western powers (not just European, also American, Russian and Japanese) and humiliation for China. Fundamentally it was all about trade, with the treaty opening up more ports to foreign traders, allowing them to use the rivers to trade inland, and granting the British a monopoly in the opium trade.

Namtow was a port, protected by a fort, on the eastern bank of the estuary of the Pearl (or Zhujiang) River, with a hinterland that provided much of Hong Kong’s workforce. Servants, merchants, shopkeepers and artisans all commuted regularly between the mainland and Hong Kong island. This factor became significant from the British point of view in the second week of July when those living on the mainland failed to return to Hong Kong, and those Chinese living on the island left. The belief was that this withdrawal of labour was the result of an order from the local Chinese authorities, and Hong Kong was faced with disaster, as all the island’s food supplies depended upon the mainland. Moreover it raised some bitter memories for the British.

Some eighteen months earlier, in late 1856, the Chinese governor in Canton had instructed all Chinese working for Europeans to return to their homes, on pain of death. The command cannot have been obeyed totally, as in January 1857 the colony was still being provided with bread baked by Chinese. Unfortunately for the European population one day’s baking was enhanced by the addition of arsenic to the dough. Fortunately for them it was so diluted in the process that no-one died immediately, although a number were permanently affected, including Maria, the wife of Sir John Bowring, Governor of Hong Kong. Bowring was a man of impeccable liberal credentials, a man who had supported reform in both Britain and Hong Kong, but the poisoned bread understandably soured him, and when the threat reappeared he was willing to take firm action.

By the third week of July 1858 most Chinese residents of Hong Kong had left the colony. No supplies were coming from the mainland, markets had no provisions, shops were closed, all Chinese merchants and shopkeepers had withdrawn, and European merchants were raising concerns about running their businesses without workers. An extraordinary meeting was held on the 29th July, and came to a resolution; the colony would act with force should the Chinese authorities not allow people back and resume supplies.

The districts from where the menaces emanate …… are threatened

with the retributive vengeance of the British Government

Over the following weeks the proclamation was delivered to the various Chinese towns around Hong Kong, although it must be assumed that by the 9th August, when the gunboat HMS Starling approached Namtow, every Chinese official within a hundred miles would have been aware of the resolution. The Starling was flying a “flag of truce”, but given that neither side trusted each other an inch it is not surprising that the Chinese in Namtow ignored the white flag and opened fire, forcing the ship to withdraw. In British eyes this was an insult and a humiliation. Retribution would have to be sought.

At nine in the morning on August 11th British forces landed in a suburb to the south-east of the city and advanced in two parallel lines. On the seaward road an advance party of a naval brigade under Captain Slight of HMS Sanspareil fought its way towards the fort, taking casualties from attacks down the intersecting streets. Further inland another force, mainly of the 59th Foot under Major Romer, advanced, pausing whenever shade was available, “the heat being fearful”. Royal Marines and the 12th Madras Native Infantry were kept in reserve.

By one o’clock troops were in position, the assault ladders were ready, and the attack began. Three ladders were laid and the first men up were the officers: Captain Slight, Commander Saumarez of HMS Cormorant and Captain William Francis Lambert. As all the British troops, including those in reserve, poured over after them the battle did not last long. By two o’clock the fort was in the attackers’ hands, and its destruction began. Both it and the surrounding city were razed, showing the Chinese that the British could not be treated with disdain.

What happened to William Lambert?

As he was climbing the ladder an altercation started behind him. A lascar seaman from the Cormorant and a soldier of the 59th jostled to be next up. As they struggled the seaman’s gun went off, and its bullet hit Lambert in the groin. He died the following day, never having even entered the fort, a rather sad and sordid footnote to a rather sad and sordid episode. Both sides could have avoided the fight, but honour had to be assuaged. Even Lambert’s death was the result of two men fighting for the privilege of being second up that ladder.

Ironically he was not the only officer to be a victim of friendly fire. Twenty-five year old Lieutenant Robert William Danvers of the 70th Bengal Native Infantry, who had been attached to the attacking force, was supervising the re-embarkation of the troops the day after the battle. All troops were ordered to discharge their muskets before going on board, as a result of which Danvers was shot through the body. Back home in London his parents placed a memorial in The Queen’s Chapel in The Savoy Hotel. His father was Clerk and Registrar to the Duchy of Lancaster, and both his brothers, Juland and James, went on to be senior civil servants, living to 1902 and 1919 respectively. If Robert had stuck with Theology he may have had a similarly long life, receiving honours and a good pension instead of a Hong Kong grave.

William Lambert’s two soldier brothers had differing lives. Captain John Lambert was killed the Battle of Sobraon in 1846, a victim of the First Sikh War. George Craster Lambert served in the Sikh wars and Burma, and on the North-west Frontier, eventually becoming Lieutenant-Colonel of the 101st regiment, the Royal Bengal Fusiliers. He retired as a Major-General to Bolton Hall, near Edlingham in Northumberland. The family's losses were not over however. George’s son, another John, was killed in the attack on Neuve Chapelle in October, 1914. The killing never seems to end.

Sources

Pictures

St. Michael's, Alnwick - from www.alnwickanglican.com

Memorial tablet to Lambert Family, St. Michael's, Alnwick - author

Portrait of Robert William Danvers - from frontispiece of his 'Letters from India and China during the Years 1854-1858'

Military

'Forgotten Souls: a Social History of the Hong Kong Cemetery' - Patricia Lim, Hong Kong University Press, 2011

'The Emigrant Soldiers' Gazetet & Cape Horn Chronicle' - ed. Second-Corporal Charles Sinnett, R.E. , published in manuscript during voyage from Gravesend to Vancouver island between 10th November 1858 and 12th April 1859 . Available on www.archwe.org.uk

'History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Vol. 1' - Whitworth Porter, Major-general Royal Engineers, Longman, Green & Co., London, 1889

'The Treaty Ports of China and Japan: a complete guide to the open ports of those countries, together with Peking, Yedo, Hong Kong and Macao' - Nicholas Belfield Dennys, republished by Cambridge University Press, 2012

The Spectator, 23rd October 1858, p.21

London Gazette, 15th October 1858 - quoting dispatch from Major-General C. T. van Straubenzee

'Britain's Forgotten Wars: colonial campaigns of the 19th Century' - Ian Hernon, Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2003

'Letters from India and China during the Years 1854-1858' - Robert William Danvers, Hazell, Watson & Viney, London, 1898

wikipedia

Genealogy

Alnwick Mercury 1st November 1858 - from www.newmp.org.uk

'The Boston and Lambert families of Northumberland - John Kenyon, www.twonorthumbrianfamilies.co.ukancestry.co.uk

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2017

Pictures

St. Michael's, Alnwick - from www.alnwickanglican.com

Memorial tablet to Lambert Family, St. Michael's, Alnwick - author

Portrait of Robert William Danvers - from frontispiece of his 'Letters from India and China during the Years 1854-1858'

Military

'Forgotten Souls: a Social History of the Hong Kong Cemetery' - Patricia Lim, Hong Kong University Press, 2011

'The Emigrant Soldiers' Gazetet & Cape Horn Chronicle' - ed. Second-Corporal Charles Sinnett, R.E. , published in manuscript during voyage from Gravesend to Vancouver island between 10th November 1858 and 12th April 1859 . Available on www.archwe.org.uk

'History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Vol. 1' - Whitworth Porter, Major-general Royal Engineers, Longman, Green & Co., London, 1889

'The Treaty Ports of China and Japan: a complete guide to the open ports of those countries, together with Peking, Yedo, Hong Kong and Macao' - Nicholas Belfield Dennys, republished by Cambridge University Press, 2012

The Spectator, 23rd October 1858, p.21

London Gazette, 15th October 1858 - quoting dispatch from Major-General C. T. van Straubenzee

'Britain's Forgotten Wars: colonial campaigns of the 19th Century' - Ian Hernon, Sutton Publishing, Stroud, 2003

'Letters from India and China during the Years 1854-1858' - Robert William Danvers, Hazell, Watson & Viney, London, 1898

wikipedia

Genealogy

Alnwick Mercury 1st November 1858 - from www.newmp.org.uk

'The Boston and Lambert families of Northumberland - John Kenyon, www.twonorthumbrianfamilies.co.ukancestry.co.uk

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2017