THE ATTACK ON ALGIERS, 1816

Midshipman Richard Calthrop, H.M.S. Leander

All Saints, West Ashby, Lincolnshire

West Ashby is a small village between Horncastle and Louth in northern Lincolnshire, with a Grade 1 Listed parish church that has a fulsome tribute to Midshipman Richard Calthrop on one of its memorial tablets. Little of the church that he would have known remains, as, as with so many other churches covered here, All Saints was much renovated and altered during the mid-Victorian period. Similarly, little remains of Richard himself; I can find nothing of him online, nor any Calthrops in West Ashby, which is surprising given that when he died he had ten surviving siblings. The only Calthrop born in West Ashby on Ancestry is Mariette, daughter of John Calthrop of Stanhoe Hall in Norfolk, so the chances are that John was Richard's brother. He, described as being "from Lincolnshire", purchased Stanhoe Hall in 1837, and it remained in the family line until the death of John’s grandson, Henry Hollway Calthrop, in 1949. Devotees of Eton College’s history will recognize Henry as College Bursar in the early decades of the last century.

So we know little of Richard, but we can blame Spain for his death, in particular that King, Carlos IV, and his ministers who in 1795 agreed an alliance with their former enemy, France, that led to Spain being at war with their former ally, Britain.

Obviously Richard was only an infant at the time, so how did that decision lead to his death twenty years later?

The Spanish decision meant that Britain no longer had access to any mainland Mediterranean ports in Europe that would allow their ships to replenish themselves. They had Gibraltar, and the Balearic Islands, and Malta, but none of those had enough hinterland to supply an active fleet, so the Navy was forced to look elsewhere, and what it saw was North Africa – the Barbary Coast.

Nominally the Barbary States were under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire, but that empire’s weakness meant that in effect the States operated as independent entities. The main centres were Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, though other ports were utilized, such as Oran (which features in one of C.S. Forester’s early Hornblower adventures). The States were not ideal allies, renowned as they were for having piracy and slavery as their main sources of income, but with no other supply bases available Britain had little option.

Other countries, however, objected to the piratical activities, especially those neutral maritime countries which had merchant ships operating in the Mediterranean. Such vessels were vulnerable to Barbary attacks, and Sweden and the USA in particular became concerned at the number of attacks on their ships, with crews having to be ransomed, financial tributes having to be negotiated, and, especially contentious, their subjects being imprisoned and enslaved.

As a consequence between 1801 and 1805 America waged a stop-start naval war against the states, raiding and blockading various ports, until a peace was declared after the Battle of Derna, near Tripoli, in 1805. This battle saw the American flag raised in victory on foreign soil for the first time, and features in the opening lines of the Marines’ Hymn:

From the halls of Montezuma

To the shores of Tripoli.

Sweden allied itself to the USA in this conflict, but Britain did not, as those supply bases were too important. Unfortunately the piracy did not cease for long, and by 1807 the raids had recommenced, and over the next few years increased towards previous levels. The USA, however, had been drawn into its own war with Britain, and so could not afford the time and ships to spare in North Africa. Then in December 1814 the war with the British ended. In March 1815 the US Congress ratified the use of naval forces against Algiers, and in May a fleet left New York. Faced with forces far superior in terms of the technology he could apply the Bey of Algiers, the most awkward of the Barbary chiefs, quickly capitulated, and by early July all American terms had been agreed and all American prisoners released.

The American terms did not, however, include European Christian prisoners, and so, at last, Napoleon having been defeated, Britain became involved. In early 1816 a diplomatic mission under Lord Exmouth was sent to negotiate the freeing of all Christian prisoners and slaves. The Beys of Tunis and Tripoli agreed, but the Bey of Algiers, Mohammad Chakar, was more recalcitrant. The success of the negotiations can be assessed from the subsequent killing of around 200 Sicilian, Corsican and Sardinian fishermen. Clearly only the threat and use of force worked.

In late July 1816 a fleet left Plymouth for Gibraltar. A few days after its arrival at the base HMS Prometheus appeared, carrying the wife and children of the British Consul in Algiers, and bearing the news that the Bey had taken prisoner the Consul and 21 members of the Prometheus' crew.

By the 28th August the fleet had taken up position in the bay at Algiers, demanding the release of all prisoners and Christian slaves. No response was forthcoming, and HMS Leander and HMS Queen Charlotte were sent into the harbour, with the Leander being “barely half a pistol shot” distant from the stone jetty. At 14.47 the defenders opened fire, and tried to board the two ships, and at 15.15 the fleet commenced bombardment of the port. At such close range the two Royal Navy ships caused great damage, but also suffered themselves. The Queen Charlotte was stood further out, but the Leander, being closest, had sails, rigging and mast destroyed by the close range guns, and was unable to steer to safety. Help was sent for, but the jolly boats carrying the messages were sunk.

So we know little of Richard, but we can blame Spain for his death, in particular that King, Carlos IV, and his ministers who in 1795 agreed an alliance with their former enemy, France, that led to Spain being at war with their former ally, Britain.

Obviously Richard was only an infant at the time, so how did that decision lead to his death twenty years later?

The Spanish decision meant that Britain no longer had access to any mainland Mediterranean ports in Europe that would allow their ships to replenish themselves. They had Gibraltar, and the Balearic Islands, and Malta, but none of those had enough hinterland to supply an active fleet, so the Navy was forced to look elsewhere, and what it saw was North Africa – the Barbary Coast.

Nominally the Barbary States were under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire, but that empire’s weakness meant that in effect the States operated as independent entities. The main centres were Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, though other ports were utilized, such as Oran (which features in one of C.S. Forester’s early Hornblower adventures). The States were not ideal allies, renowned as they were for having piracy and slavery as their main sources of income, but with no other supply bases available Britain had little option.

Other countries, however, objected to the piratical activities, especially those neutral maritime countries which had merchant ships operating in the Mediterranean. Such vessels were vulnerable to Barbary attacks, and Sweden and the USA in particular became concerned at the number of attacks on their ships, with crews having to be ransomed, financial tributes having to be negotiated, and, especially contentious, their subjects being imprisoned and enslaved.

As a consequence between 1801 and 1805 America waged a stop-start naval war against the states, raiding and blockading various ports, until a peace was declared after the Battle of Derna, near Tripoli, in 1805. This battle saw the American flag raised in victory on foreign soil for the first time, and features in the opening lines of the Marines’ Hymn:

From the halls of Montezuma

To the shores of Tripoli.

Sweden allied itself to the USA in this conflict, but Britain did not, as those supply bases were too important. Unfortunately the piracy did not cease for long, and by 1807 the raids had recommenced, and over the next few years increased towards previous levels. The USA, however, had been drawn into its own war with Britain, and so could not afford the time and ships to spare in North Africa. Then in December 1814 the war with the British ended. In March 1815 the US Congress ratified the use of naval forces against Algiers, and in May a fleet left New York. Faced with forces far superior in terms of the technology he could apply the Bey of Algiers, the most awkward of the Barbary chiefs, quickly capitulated, and by early July all American terms had been agreed and all American prisoners released.

The American terms did not, however, include European Christian prisoners, and so, at last, Napoleon having been defeated, Britain became involved. In early 1816 a diplomatic mission under Lord Exmouth was sent to negotiate the freeing of all Christian prisoners and slaves. The Beys of Tunis and Tripoli agreed, but the Bey of Algiers, Mohammad Chakar, was more recalcitrant. The success of the negotiations can be assessed from the subsequent killing of around 200 Sicilian, Corsican and Sardinian fishermen. Clearly only the threat and use of force worked.

In late July 1816 a fleet left Plymouth for Gibraltar. A few days after its arrival at the base HMS Prometheus appeared, carrying the wife and children of the British Consul in Algiers, and bearing the news that the Bey had taken prisoner the Consul and 21 members of the Prometheus' crew.

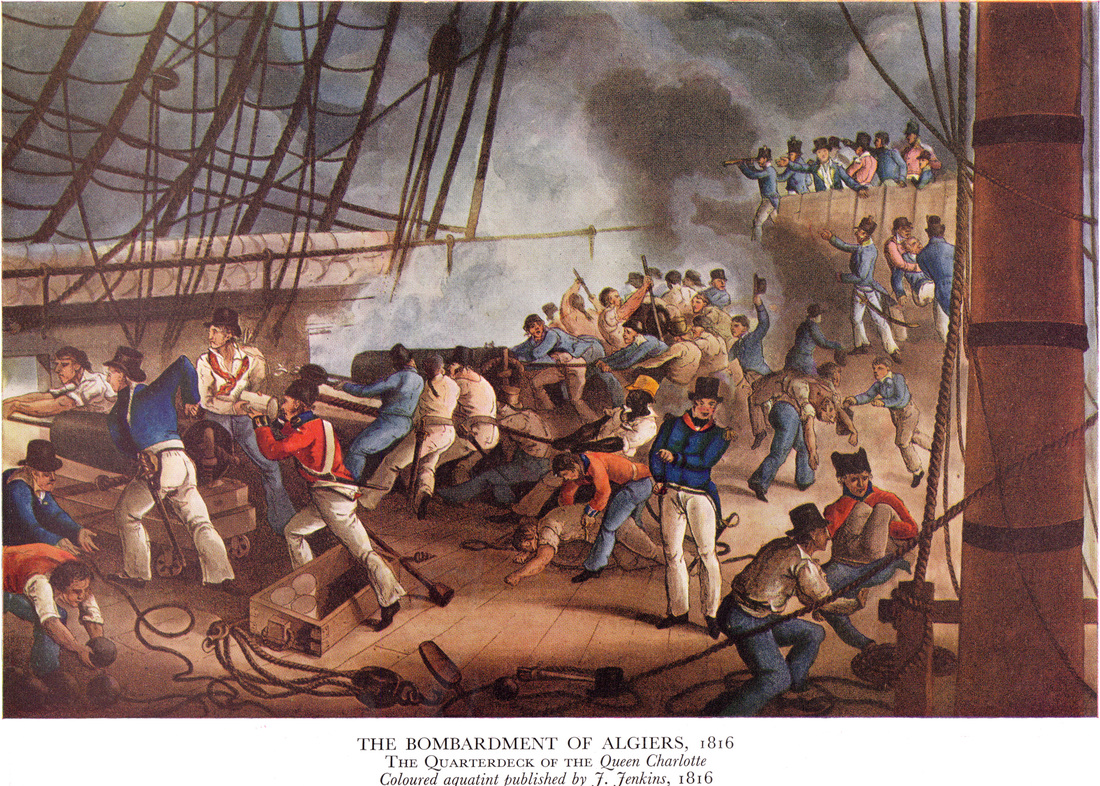

By the 28th August the fleet had taken up position in the bay at Algiers, demanding the release of all prisoners and Christian slaves. No response was forthcoming, and HMS Leander and HMS Queen Charlotte were sent into the harbour, with the Leander being “barely half a pistol shot” distant from the stone jetty. At 14.47 the defenders opened fire, and tried to board the two ships, and at 15.15 the fleet commenced bombardment of the port. At such close range the two Royal Navy ships caused great damage, but also suffered themselves. The Queen Charlotte was stood further out, but the Leander, being closest, had sails, rigging and mast destroyed by the close range guns, and was unable to steer to safety. Help was sent for, but the jolly boats carrying the messages were sunk.

It must have been during this stage of the battle that Midshipman Calthrop was killed. According to his monument he was in charge of the small arms party on the Leander, and that, “when it [the battle] raged with its utmost fury . . . a fatal ball severed his head from his body”. One can only imagine the nature of that stage of the conflict. All the shipping in the harbour had been destroyed, but the defenders on the mole could still access some guns and direct fire onto the crippled Leander. It was not until half-past ten at night that a Lieutenant George Mitford Monk managed to secure a hawser between the Leander and HMS Severn that allowed, with the assistance of a slight breeze, her to be towed out of the harbour, with 17 killed and 118 wounded, altogether nearly a third of her crew. In September the treaty was signed which released the Consul, the crew members of the Prometheus, and over a thousand Christian slaves, so it all seemed worthwhile.

The raid did not stop the pirates though. The British went back in 1819 and 1824, but it was not until the French actually invaded and conquered Algiers in 1830 that the piracy finally ceased.

Lieutenant Monk’s efforts seem to have been of mixed value, as the 1851 Census finds him still a Lieutenant, aged 60, in Greenwich Hospital, where he was Superintendent, and he died in 1858, leaving effects of under £300. His life-saving genes seem to have been passed on though; one son was a medical student, his son-in-law was a naval surgeon and then Inspector-General of Hospitals, and a grandson also became a naval surgeon. Even his eldest son, who became a stockbroker, can be found in 1891 living in Great Ormond Street, then as now the site of the famous children's hospital.

The raid did not stop the pirates though. The British went back in 1819 and 1824, but it was not until the French actually invaded and conquered Algiers in 1830 that the piracy finally ceased.

Lieutenant Monk’s efforts seem to have been of mixed value, as the 1851 Census finds him still a Lieutenant, aged 60, in Greenwich Hospital, where he was Superintendent, and he died in 1858, leaving effects of under £300. His life-saving genes seem to have been passed on though; one son was a medical student, his son-in-law was a naval surgeon and then Inspector-General of Hospitals, and a grandson also became a naval surgeon. Even his eldest son, who became a stockbroker, can be found in 1891 living in Great Ormond Street, then as now the site of the famous children's hospital.

The Bombardment of Algiers by George Chambers Sr. (1803-1840). Commissioned for Lord Exmouth in 1836. The centre background depicts the Queen Charlotte, with the Leander beyond her.

The Bombardment of Algiers by George Chambers Sr. (1803-1840). Commissioned for Lord Exmouth in 1836. The centre background depicts the Queen Charlotte, with the Leander beyond her.

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF RICHARD CALTHROP WHO GALLANTLY FOUGHT AND FELL IN DEFENCE OF CHRISTIAN LIBERTY IN THE DREADFUL BUT EVER MEMORABLE ATTACK UPON ALGIERS ON THE 27TH DAY OF AUGUST 1816 AGED 23 YEARS. HE WENT TO SEA AT THE EARLY AGE OF THIRTEEN AND AFTER EIGHT YEARS SPENT IN THE MOST ACTIVE SERVICE DURING WHICH PERIOD HE HAD BEEN IN SEVERAL PARTIAL BUT SEVERE ENGAGEMENTS WENT OUT UPON PROMOTION AS AN ADMIRALTY MIDSHIPMAN ABOARD THE LEANDER IN THE ABOVE EXPEDITION. IN THIS SHIP CARRYING 56 GUNS HE HAD THE COMMAND OF THE SMALL ARM PARTY AND ALMOST AT THE CONCLUSION OF THAT TREMENDOUS ENGAGEMENT AND WHEN IT RAGED WITH ITS UTMOST FURY AS HE WAS ANIMATING SEAMEN TO EXERTIONS AGAINST THE MOST FEROCIOUS ENEMIES OF MANKIND A FATAL BALL SEVERED HIS HEAD FROM HIS BODY AND THUS PERISHED IN RELIGOUS, HOLY CAUSE THIS PROMISING AND INTREPID YOUTH, WITHOUT A PANG AND IN THE VERY GLOWING MOMENT OF VICTORY. FROM A RESPECT TO HIS MANLY VIRTUES, THIS SACRED STONE IS HERE ERECTED BY AN AFFECTIONATE MOTHER AND TEN SURVIVING BROTHERS AND SISTERS

Sources

Picture credits

All Saints Church, West Ashby - Dave Hitchborne, from geograph.org.uk

het Bombardement van Algiers by Martinus Schouman (1770-1848) - Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Quarterdeck of the Queen Charlotte - published by J. Jenkins, 1816; on Wikimedia Commons

Bombardment of Algiers 1816 by George Chambers (1803-40) - National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Genealogy Sites

http://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/en-435221-church-of-all-saints-west-ashby-lincolns

http://stanhoe.org/history/notes/estate-sale-1932

www.ancestry.co.uk

Military Sites

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Leander_(1813)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Barbary_War

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Barbary_War

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombardment_of_Algiers_(1816)

http://www.ageofnelson.org/MichaelPhillips/info.php?ref=1310

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~pbtyc/Naval_History/Vol_VI/P_406.html

Paper-based

C. S. Forester, 'Mr. Midshipman Hornblower' (1950)

Philip J. Haythornthwaite, 'The Colonial Wars Source Book' (BCA, London, 1995)

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2013