THE SINGAPORE MUTINY, 1915

Captain Moira Francis Allan Maclean, Malay State Guides

Holy Trinity, Springfield, Essex and St. Andrew's Cathedral, Singapore

The Man

Moira Maclean was a Texan, born in the mid-state town of Colorado City in November 1883, but by 1891 he was in England, living with his maternal grandmother, Sophia Russell, in Springfield, Essex. She was an insurance agent, picking up the business of her husband Edward after his death. The street, Meadowside, is still there, although number 3 appears to have gone.

Presumably Moira was moved back to England for his education, as he spent the 1890s as a member of School House at Oundle School in Northamptonshire. His obituary in the college magazine says he was a member of the School XV; I wonder how many other rugby-playing Texans were around in the 1890s.

After leaving Oundle in 1900 Maclean joined the Indian Army, and spent over a decade being promoted through the commissioned roles until late 1913, when as Captain he was placed in command of the Mountain Battery of the Malay State Guides. Modelled on the famous Guides Companies of the North-West Frontier this was a regiment comprised of Indian sepoys, principally Sikh, but also with companies of Pathans and Punjabi Muslims. Its job was to maintain the internal defence of the Federated Malay States, an explicitly stated role which was soon to become significant.

Maclean had been in post for a year when, in October, 1914, the Indian Army's 5th Light Infantry arrived in Singapore. This was a regiment which comprised Pathan and Rajput Muslims, with most of its officers British, but it was not a happy regiment, and was to become even more unhappy.

The Background

The major problem, initially, appears to lie with the commander of the regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel E. V. Martin. He was a deeply unpopular man, particularly with his officers, to whom he rarely spoke directly, preferring to use his second-in-command as a conduit. At least two of his senior officers had applied to leave the regiment, and this unrest among the officers was transmitted to the sepoys. They had no faith in their commander, and were losing respect for their squabbling officer body as a whole.

Given the wartime situation such unrest was not good. In India an independence party, the Ghadar (with its headquarters in California) was fomenting trouble in the army, with the ultimate aim of forcing the British out of India. By December 1914 concerns were being expressed about the interception of seditious letters within the regiment, and two anti-British activists in Singapore (a preacher, Nur Alam Shah, and a coffee-shop owner, Kassim Mansur) were suspected of having had contact with the sepoys.

A similar state of unrest existed in the Malay State Guides. Relations between the men and their British officers were poor, and the Indian officers apparently lacked the men's respect. The Guides anticipated being sent abroad, but there were concerns about their willingness and their ability to fight. Maclean's opinion can be gleaned from a report that he considered many of his men to be "too old to be good soldiers".

In December 1914 the orders came for the Guides to be posted to East Africa, but they refused to go, insisting that their terms of service specified only internal action in Malaya. In this refusal the Indian officers sided with the men. A Court of Inquiry into the complaint found that the main reason for the refusal was probably financial, and that many of the officers and men had monetary interests in Malaya that they did not wish to leave. Whatever the cause, the Guides were sent back to Malaya, apart from one Mountain Battery of Sikhs, a hundred men, which remained under the command of Captain Moira Maclean.

The unrest was clearly not confined to Singapore. In January 1915, in Bombay, members of the 130th Baluchi Regiment mutinied. The dissatisfaction in the ranks of the Indian Army was spreading.

The issues were more complicated than just the stirrings of the Ghadar party. Many of the sepoys felt a real unease about being sent to fight abroad, feeling that the war being fought in Europe was not their war, and so should not involve them. Stories of high casualty rates in France were filtering back, and rumours were also circulating that Indian troops would be used to fight against the Turks in the Middle East, thus pitting Muslim sepoys against their co-religionists. Concern about this possibility was enhanced when the Sultan of Turkey issued a fatwa against the British.

So tensions were present, and known about, when, in February 1915, the 5th Light Infantry were advised to ready themselves for an overseas posting. On February 15th the General Officer Commanding Singapore addressed the farewell parade, but omitted to mention, amongst all his fine words, where the regiment was being posted to. In fact they were being sent to Hong Kong, but as the sepoys were not told many thought that their suspicions about being forced to fight the Turks were being realised.

The action

At 3.30 p.m. that day the four Rajput companies of the regiment rebelled, and were joined by some of the Sikhs of the Mountain Battery (the Light Infantry Pathan companies did not mutiny, but nor did they fight the mutineers). Two British officers present attempted to quell the rising, and were shot and killed by two of the sepoys. Thus did Captain Moira Maclean, late of Colorado City, Texas, become one of the first casualties of the Singapore Mutiny.

The mutineers then headed for the Tanglin barracks, which housed the ammunition store as well as three hundred and nine German internees, mostly sailors from ships trapped in the harbour when war was declared. Resistance from the British and Indian troops there was overcome (ten British and three loyal Indians killed, as well as one German caught in cross-fire). As they looted the ammunition the rebels invited the internees to join them but the Germans refused, although thirty-five took advantage of the confusion to escape, eventually arriving in the Dutch East Indies.

Moving through the city the mutineers killed a number of Chinese civilians at Keppel Harbour and Pasir Panjang, while a large force attacked Lieutenant-Colonel Martin's bungalow. Fortunately for Martin and the three men with him at the time a detachment of eighty men of the Malay States Volunteer Rifles had been training nearby, and they joined in the defence of the bungalow. The siege lasted through the night, but when morning came the defenders were still there, and already the mutiny was almost over.

On the evening of the 15th Royal Marines from HMS Cadmus had landed, and the next day they and local forces moved against the rebels. The regimental barracks were retaken, and the mutineers scattered.

On the 17th four foreign warships (French, Russian and Japanese) steamed into the harbour and landed marines. Now outnumbered the mutineers' cause was lost. Some died in firefights, many surrendered, and a few escaped into the jungle. Forty-seven British nationals, military and civilian had been killed, and thirteen Chinese-Singaporean civilians. An estimated two hundred mutineers had died.

The Aftermath

That latter number was to rise as the court martial ran their course. Over the following three months two hundred sepoys were tried, and of those sixty-four were transported for life, and forty-seven were executed at Outran Prison, by firing squad before a public audience of thousands. The coffee-house owner, Kassim Munsoor, was also executed, and the preacher, Nur Alam Shah, deported.

The remnants of the 5th Light Infantry were eventually sent to Africa in July 1915, fighting in the Cameroons and German East Africa. There they fought well alongside the Malay State Guides, who, having quelled a tribal uprising in Malaya, found themselves posted to Africa.

Colonel E. V. Martin, despite the defence of his bungalow, was heavily criticised by the subsequent Court of Inquiry, and retired. The only action he saw in the Great War was the defence of his own house against his own men.

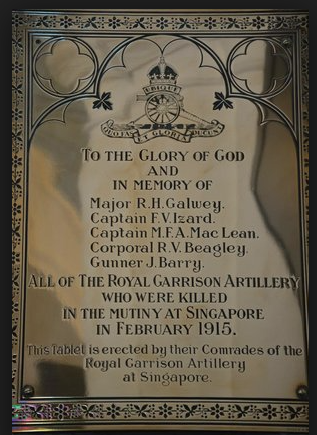

Moira Maclean has two memorials: one in St. Andrew's, Singapore, alongside the names of the other British casualties; the other in Holy Trinity Church, Springfield, near Chelmsford, the town to where he was sent from the Wild West to gain his education on the playing fields of Oundle.

Moira Maclean was a Texan, born in the mid-state town of Colorado City in November 1883, but by 1891 he was in England, living with his maternal grandmother, Sophia Russell, in Springfield, Essex. She was an insurance agent, picking up the business of her husband Edward after his death. The street, Meadowside, is still there, although number 3 appears to have gone.

Presumably Moira was moved back to England for his education, as he spent the 1890s as a member of School House at Oundle School in Northamptonshire. His obituary in the college magazine says he was a member of the School XV; I wonder how many other rugby-playing Texans were around in the 1890s.

After leaving Oundle in 1900 Maclean joined the Indian Army, and spent over a decade being promoted through the commissioned roles until late 1913, when as Captain he was placed in command of the Mountain Battery of the Malay State Guides. Modelled on the famous Guides Companies of the North-West Frontier this was a regiment comprised of Indian sepoys, principally Sikh, but also with companies of Pathans and Punjabi Muslims. Its job was to maintain the internal defence of the Federated Malay States, an explicitly stated role which was soon to become significant.

Maclean had been in post for a year when, in October, 1914, the Indian Army's 5th Light Infantry arrived in Singapore. This was a regiment which comprised Pathan and Rajput Muslims, with most of its officers British, but it was not a happy regiment, and was to become even more unhappy.

The Background

The major problem, initially, appears to lie with the commander of the regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel E. V. Martin. He was a deeply unpopular man, particularly with his officers, to whom he rarely spoke directly, preferring to use his second-in-command as a conduit. At least two of his senior officers had applied to leave the regiment, and this unrest among the officers was transmitted to the sepoys. They had no faith in their commander, and were losing respect for their squabbling officer body as a whole.

Given the wartime situation such unrest was not good. In India an independence party, the Ghadar (with its headquarters in California) was fomenting trouble in the army, with the ultimate aim of forcing the British out of India. By December 1914 concerns were being expressed about the interception of seditious letters within the regiment, and two anti-British activists in Singapore (a preacher, Nur Alam Shah, and a coffee-shop owner, Kassim Mansur) were suspected of having had contact with the sepoys.

A similar state of unrest existed in the Malay State Guides. Relations between the men and their British officers were poor, and the Indian officers apparently lacked the men's respect. The Guides anticipated being sent abroad, but there were concerns about their willingness and their ability to fight. Maclean's opinion can be gleaned from a report that he considered many of his men to be "too old to be good soldiers".

In December 1914 the orders came for the Guides to be posted to East Africa, but they refused to go, insisting that their terms of service specified only internal action in Malaya. In this refusal the Indian officers sided with the men. A Court of Inquiry into the complaint found that the main reason for the refusal was probably financial, and that many of the officers and men had monetary interests in Malaya that they did not wish to leave. Whatever the cause, the Guides were sent back to Malaya, apart from one Mountain Battery of Sikhs, a hundred men, which remained under the command of Captain Moira Maclean.

The unrest was clearly not confined to Singapore. In January 1915, in Bombay, members of the 130th Baluchi Regiment mutinied. The dissatisfaction in the ranks of the Indian Army was spreading.

The issues were more complicated than just the stirrings of the Ghadar party. Many of the sepoys felt a real unease about being sent to fight abroad, feeling that the war being fought in Europe was not their war, and so should not involve them. Stories of high casualty rates in France were filtering back, and rumours were also circulating that Indian troops would be used to fight against the Turks in the Middle East, thus pitting Muslim sepoys against their co-religionists. Concern about this possibility was enhanced when the Sultan of Turkey issued a fatwa against the British.

So tensions were present, and known about, when, in February 1915, the 5th Light Infantry were advised to ready themselves for an overseas posting. On February 15th the General Officer Commanding Singapore addressed the farewell parade, but omitted to mention, amongst all his fine words, where the regiment was being posted to. In fact they were being sent to Hong Kong, but as the sepoys were not told many thought that their suspicions about being forced to fight the Turks were being realised.

The action

At 3.30 p.m. that day the four Rajput companies of the regiment rebelled, and were joined by some of the Sikhs of the Mountain Battery (the Light Infantry Pathan companies did not mutiny, but nor did they fight the mutineers). Two British officers present attempted to quell the rising, and were shot and killed by two of the sepoys. Thus did Captain Moira Maclean, late of Colorado City, Texas, become one of the first casualties of the Singapore Mutiny.

The mutineers then headed for the Tanglin barracks, which housed the ammunition store as well as three hundred and nine German internees, mostly sailors from ships trapped in the harbour when war was declared. Resistance from the British and Indian troops there was overcome (ten British and three loyal Indians killed, as well as one German caught in cross-fire). As they looted the ammunition the rebels invited the internees to join them but the Germans refused, although thirty-five took advantage of the confusion to escape, eventually arriving in the Dutch East Indies.

Moving through the city the mutineers killed a number of Chinese civilians at Keppel Harbour and Pasir Panjang, while a large force attacked Lieutenant-Colonel Martin's bungalow. Fortunately for Martin and the three men with him at the time a detachment of eighty men of the Malay States Volunteer Rifles had been training nearby, and they joined in the defence of the bungalow. The siege lasted through the night, but when morning came the defenders were still there, and already the mutiny was almost over.

On the evening of the 15th Royal Marines from HMS Cadmus had landed, and the next day they and local forces moved against the rebels. The regimental barracks were retaken, and the mutineers scattered.

On the 17th four foreign warships (French, Russian and Japanese) steamed into the harbour and landed marines. Now outnumbered the mutineers' cause was lost. Some died in firefights, many surrendered, and a few escaped into the jungle. Forty-seven British nationals, military and civilian had been killed, and thirteen Chinese-Singaporean civilians. An estimated two hundred mutineers had died.

The Aftermath

That latter number was to rise as the court martial ran their course. Over the following three months two hundred sepoys were tried, and of those sixty-four were transported for life, and forty-seven were executed at Outran Prison, by firing squad before a public audience of thousands. The coffee-house owner, Kassim Munsoor, was also executed, and the preacher, Nur Alam Shah, deported.

The remnants of the 5th Light Infantry were eventually sent to Africa in July 1915, fighting in the Cameroons and German East Africa. There they fought well alongside the Malay State Guides, who, having quelled a tribal uprising in Malaya, found themselves posted to Africa.

Colonel E. V. Martin, despite the defence of his bungalow, was heavily criticised by the subsequent Court of Inquiry, and retired. The only action he saw in the Great War was the defence of his own house against his own men.

Moira Maclean has two memorials: one in St. Andrew's, Singapore, alongside the names of the other British casualties; the other in Holy Trinity Church, Springfield, near Chelmsford, the town to where he was sent from the Wild West to gain his education on the playing fields of Oundle.

Sources

Photos

Moira Francis Allan Maclean - from Maclean's obituary on www.oundleschool.org.uk

Holy Trinity Church - holytrinityspringfield.org.uk

The public executions of convicted sepoy mutineers at Outram Road, Singapore

Memorial at St. Andrew's, Singapore - from www.isard.one-name.net

Military

www.wfadublin.webs.com - an Irish organisation with a focus on World War One, and a site with some interesting pages

The Adelaide Advertiser, 25th february 1915 - online at www.trove.nla.gov.au

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMSEmden

Times of Malaya 11th August 2011 - from timesofmalaya.blogspot.co.uk

Report of the Malay State Guides for the Year 1913 - commoner.um.edu.my

www.livelb.nationalarchives.co.uk

B'etween Two Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971', Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun (Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte. Ltd, 2011)

www.roll-of-honour.com

'Indian Mutiny in Singapore 1915: people who observed the scene and people who heard the news', Sho Kuwajima, Osaka University of Foreign Studies - paper on www.nzasia.org.nz

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.connectedhistories.org

www.seax.essexcc.gov.uk

www.oundleschool.org.uk - Maclean's obituary can be found in the World War 1 Memorials section

Photos

Moira Francis Allan Maclean - from Maclean's obituary on www.oundleschool.org.uk

Holy Trinity Church - holytrinityspringfield.org.uk

The public executions of convicted sepoy mutineers at Outram Road, Singapore

Memorial at St. Andrew's, Singapore - from www.isard.one-name.net

Military

www.wfadublin.webs.com - an Irish organisation with a focus on World War One, and a site with some interesting pages

The Adelaide Advertiser, 25th february 1915 - online at www.trove.nla.gov.au

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMSEmden

Times of Malaya 11th August 2011 - from timesofmalaya.blogspot.co.uk

Report of the Malay State Guides for the Year 1913 - commoner.um.edu.my

www.livelb.nationalarchives.co.uk

B'etween Two Oceans (2nd Edn): A Military History of Singapore from 1275 to 1971', Malcolm H. Murfett, John Miksic, Brian Farell, Chiang Ming Shun (Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte. Ltd, 2011)

www.roll-of-honour.com

'Indian Mutiny in Singapore 1915: people who observed the scene and people who heard the news', Sho Kuwajima, Osaka University of Foreign Studies - paper on www.nzasia.org.nz

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.connectedhistories.org

www.seax.essexcc.gov.uk

www.oundleschool.org.uk - Maclean's obituary can be found in the World War 1 Memorials section