THE YOUNGHUSBAND EXPEDITION, TIBET, 1904

Captain John Charles Pulleine Craster, 46th Punjabis

Craster Harbour and Holy Trinity Church, Embleton

Captain John Charles Pulleine Craster, 46th Punjabis

Craster Harbour and Holy Trinity Church, Embleton

The Man

When the 14th Century Crasters built a pele tower a mile south of Dunstanburgh Castle on the Northumbrian coast they probably did not think that their ancestors would still be living there six hundred years later, nor that one of their name would die fighting, not Border reivers, but Buddhist monks. Nowadays you can stay in an apartment in the tower if you wish, but visiting the site of Captain Craster’s death might be more difficult.

By 1871 the latest Craster living in the tower was John, who had been born, unlike his Northumbrian-bred ancestors, in Longueville House in County Cork (now a hotel). He and his Scottish-born wife Charlotte had six children: Thomas [born 1860]; Amy [1862]; Edmund [1863]; William [1867]; John [1871]; and Walter [1874]. Two of the children, Thomas and Amy, stayed at home, and lived on in the tower after their father’s death. Edmund, William and Walter left for the colonies; Canada, the USA and Rhodesia respectively. John joined the army.

He joined the county regiment, the Northumberland Fusiliers, receiving his first commission in January 1892, when he was made 2nd-Lieutenant. Three years later he left the regiment for a place on the Indian Army Staff, with whom he saw action at various engagements during the Tirah Campaign on the North-West Frontier in 1898-99. Promoted to Lieutenant in October 1899 he joined the 46th Punjabis when it was raised in October 1900, being made Captain in 1901, and then Adjutant, the position he was holding when Colonel Francis Younghusband was ordered by India’s Governor-General, Lord Curzon, to prepare his ‘Tibetan Frontier Commission' for a ‘trade mission’ to Tibet.

The Background

The inverted commas are mine. The Commission was flagrantly waiting for an opportunity to be transformed into a military operation. Led by Younghusband (who was, although India-born, also a scion of a Northumbrian family, from Bamburgh, just up the coast from Craster), the troops were commanded by Brigadier Sir James Macdonald (who had a distinguished reputation as an explorer and expedition leader),and numbered three thousand Pathan and Gurkha soldiers, with a further seven thousand support personnel. For a mission that was to secure a trade agreement and agree the Sikkim-Tibet border the numbers seem excessive. Curzon wanted far more than a Frontier Commission when he ordered Younghusband’s expedition.

In 1893 Britain had signed a trade agreement with China believing that Chinese authority extended over Tibet, as indeed it once had. By the close of the century, however, with the Qing Dynasty struggling, China's hold had weakened, and Tibet, with a strong political leader in the 13th Dalai Lama, operated as an independent entity. When the Dalai Lama heard of the trade agreement he rejected it, and British suspicions were raised.

They were raised because Curzon had been brought up in the tradition of The Great Game, the power play-off between Russia and Britain along India’s northern borders. His concerns about the rejected trade agreement were exacerbated by the knowledge that one of the Dalai Lama’s closest advisors was a Russian subject, albeit a practising Buddhist monk, and that he was being used as an envoy by Russia. Despite Russia claiming it had no intention of getting involved in Tibet Curzon saw the links as a threat, and was determined to ensure that if China was not to control Tibet, neither was Russia; hence the Younghusband Expedition.

The Campaign

Whatever the ultimate intention, Younghusband could not just march over another country’s border with three thousand troops, and so he awaited an excuse. In early December 1903 he received news that some Nepalese yak-herders, who had drifted over the poorly-defined frontier, had been forcibly returned. Interpreting this as an act of aggression, Younghusband justified his crossing into Tibet.

The force wintered on the border, Macdonald training his troops, before advancing in March. They encountered no opposition until the end of the month, on the 31st, in a pass near a village named as Guru. About three thousand Tibetans (armed with bows, spears, rocks and matchlocks, the latter being firearms which the British army had not used for two centuries) were gathered behind a five-foot high rock wall which stretched across the path, and they refused to let the British force pass. Scuffles broke out, and a Tibetan official shot a Sikh soldier. The British troops, who now flanked the Tibetans on both sides with Maxim Guns, were ordered to open fire.

The outcome was predictable. For a grand total of twelve wounded the British killed between six and seven hundred Tibetans, with Lieutenant Arthur Hadon, who commanded a Maxim Gun detachment, saying afterwards, “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire”.

Nine days later, in a pass named Red Idol Gorge, the Tibetans again tried to block Younghusband’s progress. Again their attempt was futile. Under artillery fire, and with Gurkhas firing down on them from the flanks, the Tibetans withdrew, leaving over two hundred dead.

There was now a pause. The killings near Guru had not gone down well in London, and Younghusband was reluctant to move on to the capital, Lhasa, without clear justification. Fortunately he got this in early May when he was based at a garrison post at Chang Lo, separated from the main force. Some Tibetans attacked, the attack was repulsed, and Younghusband had his excuse.

Assuming that marching on to Lhasa would provoke more opposition than so far encountered, Macdonald sent for reinforcements, which included the 40th Pathans, who had attached to them, following his volunteering for the expedition, Captain John Charles Pulleine Craster.

The reinforcements arrived in June, and the march to Lhasa began. The major obstacle en route was the fort, or dzong, at Gyantse, with two fortified monasteries preceding it, at Naini and Tsechen. Naini was taken on June 26th, and on the 28th Macdonald attacked Tsechen.

The Action

Tsechen consisted of a monastery and fort overlooking a village, and it was raining heavily when two companies of Gurkhas were sent to attack the monastery from above and behind, while four companies of the 40th Pathans, under cover of artillery fire, began to march up the steep hillside to attack the village. A medical officer, Captain Cecil Mainprise, described the action as “a splendid fight, as the village was situated high up, and we could see the effects of the guns beautifully – the shrapnel shells bursting over the tower’s small forts and the enemy dashing about in all directions”.

Despite the steep slope and the pouring rain the 40th Pathans reached the village, which then had to be cleared street by street. The monastery above had a garrison of of twelve hundred monks, who offered resistance with “shots and a heavy volley of stones and rocks”, although their matchlocks were rendered mostly ineffectual by the rain, which made igniting the powder difficult, and also by the steepness of the angle down which they were aiming, as without sufficient wadding the bullets simply rolled out of the barrels.

While the Gurkhas tackled the monastery, the Pathans cleared the village, meeting little resistance other than that “from a band of men in one house”. Even that resistance led to only two casualties, but one of them was Captain John Craster, “killed outright by a musket ball fired at point-blank range” through his head, when “almost the whole place was in the hands of the 40th”.

Aftermath

Craster was the most senior fatality of the expedition. With Tsechen taken, Macdonald successfully attacked Gyantse Dzong on July 6th. For breaching the defences a Victoria Cross was awarded to Lieutenant John Grant, and its Indian Army equivalent, the Indian Order of Merit First Class, awarded to Havildar Pun. On August 3rd the force arrived at Lhasa. Although the Dalai Lama was not present to authorise any treaty Younghusband insisted on one, to be signed by the Dalai Lama’s representatives. This agreement, signed the day after Younghusband’s arrival in the city, recognized Britain’s priority rights to trade with Tibet, formalized the Sikkim frontier, pledged Tibet not to have relationships with other powers, and declared that Tibet would pay a large indemnity for British losses. It did not seem to matter that Tibet had little worthwhile to trade, that China still claimed suzerainty, that the country did not have the financial resources to pay the compensation, nor that the Dalai Lama had not authorized the agreement. Younghusband had got to Lhasa, and Curzon could now feel confident that Russian armies would not come marching over the Himalayas.

Afterwards

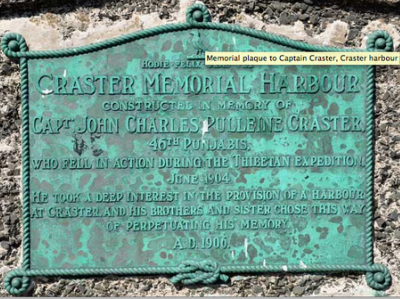

Back in Northumberland Captain Craster’s estate was put to good use. His siblings, Thomas and Amy, put his money towards building a new harbour at Craster, a project John had always advocated, and that is the harbour there now, complete with his memorial. Thomas and Amy lived the rest of their lives at Craster Tower. It then passed to Thomas' son, John, and following him was inherited by his cousins, who divided it into three apartments and own it now. Of the other brothers, William died in Idaho in 1917, but Edmund prospered in British Columbia, where his family still live. Walter founded the wonderfully named Rhodesia Rickshaw Company in Salisbury, which eventually developed into an engineering firm, Craster International.

Captain Cecil Mainprise served throughout the First World War in various theatres, eventually becoming a Major-General and Commandant of the Royal Medical College before retiring in 1926. He died in Aldershot in 1951, aged 77. Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Francis Younghusband eventually retired to England, lived at Westerham in Kent, and died at Lytchett Minster in Dorset in 1942, aged 79. Sir James Macdonald became General Officer Commanding, Mauritius before retiring in 1912. He died in Bournemouth in 1927, aged 65. John Craster has his memorial in the harbour he never saw.

When the 14th Century Crasters built a pele tower a mile south of Dunstanburgh Castle on the Northumbrian coast they probably did not think that their ancestors would still be living there six hundred years later, nor that one of their name would die fighting, not Border reivers, but Buddhist monks. Nowadays you can stay in an apartment in the tower if you wish, but visiting the site of Captain Craster’s death might be more difficult.

By 1871 the latest Craster living in the tower was John, who had been born, unlike his Northumbrian-bred ancestors, in Longueville House in County Cork (now a hotel). He and his Scottish-born wife Charlotte had six children: Thomas [born 1860]; Amy [1862]; Edmund [1863]; William [1867]; John [1871]; and Walter [1874]. Two of the children, Thomas and Amy, stayed at home, and lived on in the tower after their father’s death. Edmund, William and Walter left for the colonies; Canada, the USA and Rhodesia respectively. John joined the army.

He joined the county regiment, the Northumberland Fusiliers, receiving his first commission in January 1892, when he was made 2nd-Lieutenant. Three years later he left the regiment for a place on the Indian Army Staff, with whom he saw action at various engagements during the Tirah Campaign on the North-West Frontier in 1898-99. Promoted to Lieutenant in October 1899 he joined the 46th Punjabis when it was raised in October 1900, being made Captain in 1901, and then Adjutant, the position he was holding when Colonel Francis Younghusband was ordered by India’s Governor-General, Lord Curzon, to prepare his ‘Tibetan Frontier Commission' for a ‘trade mission’ to Tibet.

The Background

The inverted commas are mine. The Commission was flagrantly waiting for an opportunity to be transformed into a military operation. Led by Younghusband (who was, although India-born, also a scion of a Northumbrian family, from Bamburgh, just up the coast from Craster), the troops were commanded by Brigadier Sir James Macdonald (who had a distinguished reputation as an explorer and expedition leader),and numbered three thousand Pathan and Gurkha soldiers, with a further seven thousand support personnel. For a mission that was to secure a trade agreement and agree the Sikkim-Tibet border the numbers seem excessive. Curzon wanted far more than a Frontier Commission when he ordered Younghusband’s expedition.

In 1893 Britain had signed a trade agreement with China believing that Chinese authority extended over Tibet, as indeed it once had. By the close of the century, however, with the Qing Dynasty struggling, China's hold had weakened, and Tibet, with a strong political leader in the 13th Dalai Lama, operated as an independent entity. When the Dalai Lama heard of the trade agreement he rejected it, and British suspicions were raised.

They were raised because Curzon had been brought up in the tradition of The Great Game, the power play-off between Russia and Britain along India’s northern borders. His concerns about the rejected trade agreement were exacerbated by the knowledge that one of the Dalai Lama’s closest advisors was a Russian subject, albeit a practising Buddhist monk, and that he was being used as an envoy by Russia. Despite Russia claiming it had no intention of getting involved in Tibet Curzon saw the links as a threat, and was determined to ensure that if China was not to control Tibet, neither was Russia; hence the Younghusband Expedition.

The Campaign

Whatever the ultimate intention, Younghusband could not just march over another country’s border with three thousand troops, and so he awaited an excuse. In early December 1903 he received news that some Nepalese yak-herders, who had drifted over the poorly-defined frontier, had been forcibly returned. Interpreting this as an act of aggression, Younghusband justified his crossing into Tibet.

The force wintered on the border, Macdonald training his troops, before advancing in March. They encountered no opposition until the end of the month, on the 31st, in a pass near a village named as Guru. About three thousand Tibetans (armed with bows, spears, rocks and matchlocks, the latter being firearms which the British army had not used for two centuries) were gathered behind a five-foot high rock wall which stretched across the path, and they refused to let the British force pass. Scuffles broke out, and a Tibetan official shot a Sikh soldier. The British troops, who now flanked the Tibetans on both sides with Maxim Guns, were ordered to open fire.

The outcome was predictable. For a grand total of twelve wounded the British killed between six and seven hundred Tibetans, with Lieutenant Arthur Hadon, who commanded a Maxim Gun detachment, saying afterwards, “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire”.

Nine days later, in a pass named Red Idol Gorge, the Tibetans again tried to block Younghusband’s progress. Again their attempt was futile. Under artillery fire, and with Gurkhas firing down on them from the flanks, the Tibetans withdrew, leaving over two hundred dead.

There was now a pause. The killings near Guru had not gone down well in London, and Younghusband was reluctant to move on to the capital, Lhasa, without clear justification. Fortunately he got this in early May when he was based at a garrison post at Chang Lo, separated from the main force. Some Tibetans attacked, the attack was repulsed, and Younghusband had his excuse.

Assuming that marching on to Lhasa would provoke more opposition than so far encountered, Macdonald sent for reinforcements, which included the 40th Pathans, who had attached to them, following his volunteering for the expedition, Captain John Charles Pulleine Craster.

The reinforcements arrived in June, and the march to Lhasa began. The major obstacle en route was the fort, or dzong, at Gyantse, with two fortified monasteries preceding it, at Naini and Tsechen. Naini was taken on June 26th, and on the 28th Macdonald attacked Tsechen.

The Action

Tsechen consisted of a monastery and fort overlooking a village, and it was raining heavily when two companies of Gurkhas were sent to attack the monastery from above and behind, while four companies of the 40th Pathans, under cover of artillery fire, began to march up the steep hillside to attack the village. A medical officer, Captain Cecil Mainprise, described the action as “a splendid fight, as the village was situated high up, and we could see the effects of the guns beautifully – the shrapnel shells bursting over the tower’s small forts and the enemy dashing about in all directions”.

Despite the steep slope and the pouring rain the 40th Pathans reached the village, which then had to be cleared street by street. The monastery above had a garrison of of twelve hundred monks, who offered resistance with “shots and a heavy volley of stones and rocks”, although their matchlocks were rendered mostly ineffectual by the rain, which made igniting the powder difficult, and also by the steepness of the angle down which they were aiming, as without sufficient wadding the bullets simply rolled out of the barrels.

While the Gurkhas tackled the monastery, the Pathans cleared the village, meeting little resistance other than that “from a band of men in one house”. Even that resistance led to only two casualties, but one of them was Captain John Craster, “killed outright by a musket ball fired at point-blank range” through his head, when “almost the whole place was in the hands of the 40th”.

Aftermath

Craster was the most senior fatality of the expedition. With Tsechen taken, Macdonald successfully attacked Gyantse Dzong on July 6th. For breaching the defences a Victoria Cross was awarded to Lieutenant John Grant, and its Indian Army equivalent, the Indian Order of Merit First Class, awarded to Havildar Pun. On August 3rd the force arrived at Lhasa. Although the Dalai Lama was not present to authorise any treaty Younghusband insisted on one, to be signed by the Dalai Lama’s representatives. This agreement, signed the day after Younghusband’s arrival in the city, recognized Britain’s priority rights to trade with Tibet, formalized the Sikkim frontier, pledged Tibet not to have relationships with other powers, and declared that Tibet would pay a large indemnity for British losses. It did not seem to matter that Tibet had little worthwhile to trade, that China still claimed suzerainty, that the country did not have the financial resources to pay the compensation, nor that the Dalai Lama had not authorized the agreement. Younghusband had got to Lhasa, and Curzon could now feel confident that Russian armies would not come marching over the Himalayas.

Afterwards

Back in Northumberland Captain Craster’s estate was put to good use. His siblings, Thomas and Amy, put his money towards building a new harbour at Craster, a project John had always advocated, and that is the harbour there now, complete with his memorial. Thomas and Amy lived the rest of their lives at Craster Tower. It then passed to Thomas' son, John, and following him was inherited by his cousins, who divided it into three apartments and own it now. Of the other brothers, William died in Idaho in 1917, but Edmund prospered in British Columbia, where his family still live. Walter founded the wonderfully named Rhodesia Rickshaw Company in Salisbury, which eventually developed into an engineering firm, Craster International.

Captain Cecil Mainprise served throughout the First World War in various theatres, eventually becoming a Major-General and Commandant of the Royal Medical College before retiring in 1926. He died in Aldershot in 1951, aged 77. Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Francis Younghusband eventually retired to England, lived at Westerham in Kent, and died at Lytchett Minster in Dorset in 1942, aged 79. Sir James Macdonald became General Officer Commanding, Mauritius before retiring in 1912. He died in Bournemouth in 1927, aged 65. John Craster has his memorial in the harbour he never saw.

Sources

Photos

Captain John Craster - St. George's Gazette 30th July, 1904; www.crasterhistory.org

Craster Harbour, Northumberland - en:user:Jeandunston, Wikimedia Commons

The town Gyantse in Tiber with Dzong in the background - Thilo Schön, Wikimedia Commons

Memorial plaque to Captain Craster - Ruth Dewhirst

Military

achive.spectator.co.uk - extract from The Spectator 2nd July 1904

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Younghusbanden.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Macdonald_(engineer)

intotibet1903-04.blogspot.co.uk -

www.newspapers.com - extract from The Times 16/8/1904

'The Encyclopedia of Warfare' (Amber, London, 2014)

'India and Tibet' by Francis Edward Younghusband (Asian Educational Services, 1993)

'Into Tibet: the Early British Explorers' by George Woodcock (Faber & Faber, London, 1971)

'Lhasa and its Mysteries; with a record of the British Tibetan Expedition of 1903-04' by Laurence Austine Waddell (Courier Dover Publication, 1988)

'Tibet: The Road Ahead' by Dawa Norbu (Rider, London, 1998)

'The Unveiling of Lhasa' by Edmund Candler (Edward Arnold, London, 1905)

'With Mounted Infantry in Tibet' by Brevet-Major William John Ottley (Smith, Elder & Co., London, 1906)

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.crastercommunity.org.uk

www.crasterhistory.org.uk

'The Anglo-African Who's Who and Biographical Sketchbook', edited by Walter H. Wills (Jeppestown Press, 2006)