ACCIDENT & AMBUSH:

1ST SOMALILAND CAMPAIGN, 1901

Lieutenant Lionel Wilfred de Sausmarez, 60th King's Royal Rifle Corps

War Memorial Church, Sandhurst, Berkshire

Molesey Cemetery, West Molesey, Surrey

Captain Duncan Alexander Friederichs, Royal Engineers

St. Edith, Eaton-under-Heywood, Shropshire

Look at images of Ogadan and you see vistas of red and brown, sand and rock and scrub, camels and fighters and barren land. There is little to these eyes that can be called attractive, but there must be something, as men have fought and died there for generations: peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea was only declared in 2018, twenty years after their war began; the Ogadan National Liberation Front is active now; the area between war-torn Somalia (one of those countries even tourists avoid) and Somaliland to the west is still demarcated on some maps as a Disputed Zone; and at the turn of the twentieth century men died in the dirt there.

To be fair the British were not really interested in the region's interior. They wanted to secure the coast to ensure safe passage for ships moving between the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean, and so it was on the coast that they were concentrated, apart a few undermanned bases on key supply routes.The rock-strewn hinterland, populated by nomadic tribes tending herds of cattle and camels, was of little interest. It took a Muslim fundamentalist/ freedom-fighter/ brigand (take your pick) called Mohammad Abadullah Hassan to change the British attitude.

Mohammad became known in British lore as 'The Mad Mullah', with his followers famed as 'the whirling Dervishes', but I doubt he was mad. He followed a puritanical ascetic version of Sunni Islam that we would today call fundamentalist, and in the 1890s he began a campaign against Christians in the area. For Christian here we can also read pro-British, or at least not anti-British. Most tribes probably just wanted to get on with their lives as peacefully as possible, and that would involve trading with the British. Even if they were not Christians, trading with the Christian British made them a valid target in Dervish eyes, and so Mohammad began raiding their communities and stealing their livestock. If it continued Britain would have to get involved.

The tipping point was a Dervish raid on a Christian Ethiopian base at a town called Jijiga in July 1900. The attackers were driven off, but the assault prompted Ethiopia to suggest to the British that they coordinate efforts to drive Mohammad and his followers out of the picture, and Britain agreed.

This took time. British forces were already committed to conflicts in South Africa, West Africa and China, which meant there were not many available to send into Somalia. In December 1900 the decision was taken to order an Indian Army colonel, Eric Swayne, to raise a local force from the tribes being targeted by Mohammad, with officers and N.C.O.s drafted from the British and Indian armies. The Indian contingent were delayed, so in the first few months of 1901 Swayne had twenty British officers, and four Indian N.C.O.s posted from Aden, to arm and train a force of fifteen hundred men, mostly infantry, but including horsemen and a camel corps.

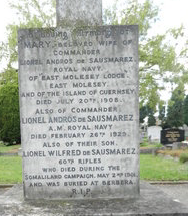

One of those officers was a Lieutenant from the King's Royal Rifle Corps, Lionel Wilfred de Sausmarez. Son of a retired Royal Navy Commander he was part of a long-established Guernsey family, although his immediate family did not settle there. By the time the twenty-one-year-old Lionel had left the Royal Military College as a Gentleman Cadet in 1895 his parents were settled in East Molesey in Surrey.. Lionel was posted to South Africa, and took part in the defence of Ladysmith before volunteering to join Swayne's force in Somalia. He was one of the officers delegated to train the raw Somali tribesmen, training unfamiliar troops with, to them, unfamiliar weapons, in an unfamiliar language, and under pressure of time. In such circumstances accidents are more likely to happen, and one did. The details are unknown, but Lieutenant de Sausmarez succumbed to "an accidental shooting incident" at Burao on May 9th 1901. Just because he was not killed in action does not make him less of a victim.

De Sausmarez just missed out on the action. On May 22nd, less than two weeks after his death, Swayne's expedition set out from Burao. After a series of skirmishes, mostly involving his mounted troops, Swayne was driving Mohammad's men out of British territory. Mohammad's men were concentrating on driving their cattle away and harassing the pursuing British force, whilst avoiding a formal fixed engagement, and it was one such encounter on July 17th that brings Captain Duncan Friederichs into the story.

A Royal Engineer, born in 1869, Friederichs was the son of Hugo,from Oldenburg in North-West Germany, who had come to Britain as a banker's clerk. As Duncan rode out in the Ogadan his mother, Isabella, was a widow, living in the rectory at Acton Scott in Shropshire, with his brother, Charles Gustave, the vicar of nearby Eaton-under-Heywood. The contrast could hardly be more stark between St. Ediths, on the wooded lower slopes of Wenlock Edge, and the undulating rocky sandhills Duncan rode towards that day, winding his way between clumps of thorny scrub. Duncan had experienced desert warfare before, having fought at Omdurman, but that was a pitched battle against men carrying swords and spears. This wasn't.

Over the sandhills Mohammad and his men were moving out of British territory, with their families and their herds. On one of those ridges, concealed in the scrub, lay a row of his riflemen, guarding the retreat. As Friederichs and his men drew close the hidden riflemen opened fire, the British turned to move out of range, but an NCO was hit, and fell to the ground. Friederichs turned to help him, but he too was hit, and his wound was fatal. Swayne realised what was happening and sent out more troops, and the riflemen vanished away after their leader. Too late for Friederichs, who was buried where he fell, the last victim of the First Somaliland Campaign. He was the last because Swayne, fearing for his depleted water supplies, decided he could no longer pursue Mohammad. With a sort-of victory secured he returned to Burao. The use of the word "First" gives an idea of how much of a victory it was. The 'Mad' Mullah would be back, and there would be more than one British grave left in the desert.

Colonel Eric Swayne went on to become Governor of British Honduras, retiring to Pucklechurch in Gloucestershire, where he died in 1929, in his mid-sixties. The last de Sausmarez to live at East Molesey Lodge was Lionel's sister, Frances. After she died the house was sold, and then demolished in 1930. The ancestral home on Guernsey is still in the family; at the time of writing, Sausmarez Manor is the only stately home on the island open to visitors. Lionel is commemorated on the family gravestone in Molesey Cemetery, and also on a memorial at Sandhurst. Duncan Friederich's memorial is in the church at Acton Scott in Shropshire, where the only things the local riflemen shoot are game birds.

To be fair the British were not really interested in the region's interior. They wanted to secure the coast to ensure safe passage for ships moving between the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean, and so it was on the coast that they were concentrated, apart a few undermanned bases on key supply routes.The rock-strewn hinterland, populated by nomadic tribes tending herds of cattle and camels, was of little interest. It took a Muslim fundamentalist/ freedom-fighter/ brigand (take your pick) called Mohammad Abadullah Hassan to change the British attitude.

Mohammad became known in British lore as 'The Mad Mullah', with his followers famed as 'the whirling Dervishes', but I doubt he was mad. He followed a puritanical ascetic version of Sunni Islam that we would today call fundamentalist, and in the 1890s he began a campaign against Christians in the area. For Christian here we can also read pro-British, or at least not anti-British. Most tribes probably just wanted to get on with their lives as peacefully as possible, and that would involve trading with the British. Even if they were not Christians, trading with the Christian British made them a valid target in Dervish eyes, and so Mohammad began raiding their communities and stealing their livestock. If it continued Britain would have to get involved.

The tipping point was a Dervish raid on a Christian Ethiopian base at a town called Jijiga in July 1900. The attackers were driven off, but the assault prompted Ethiopia to suggest to the British that they coordinate efforts to drive Mohammad and his followers out of the picture, and Britain agreed.

This took time. British forces were already committed to conflicts in South Africa, West Africa and China, which meant there were not many available to send into Somalia. In December 1900 the decision was taken to order an Indian Army colonel, Eric Swayne, to raise a local force from the tribes being targeted by Mohammad, with officers and N.C.O.s drafted from the British and Indian armies. The Indian contingent were delayed, so in the first few months of 1901 Swayne had twenty British officers, and four Indian N.C.O.s posted from Aden, to arm and train a force of fifteen hundred men, mostly infantry, but including horsemen and a camel corps.

One of those officers was a Lieutenant from the King's Royal Rifle Corps, Lionel Wilfred de Sausmarez. Son of a retired Royal Navy Commander he was part of a long-established Guernsey family, although his immediate family did not settle there. By the time the twenty-one-year-old Lionel had left the Royal Military College as a Gentleman Cadet in 1895 his parents were settled in East Molesey in Surrey.. Lionel was posted to South Africa, and took part in the defence of Ladysmith before volunteering to join Swayne's force in Somalia. He was one of the officers delegated to train the raw Somali tribesmen, training unfamiliar troops with, to them, unfamiliar weapons, in an unfamiliar language, and under pressure of time. In such circumstances accidents are more likely to happen, and one did. The details are unknown, but Lieutenant de Sausmarez succumbed to "an accidental shooting incident" at Burao on May 9th 1901. Just because he was not killed in action does not make him less of a victim.

De Sausmarez just missed out on the action. On May 22nd, less than two weeks after his death, Swayne's expedition set out from Burao. After a series of skirmishes, mostly involving his mounted troops, Swayne was driving Mohammad's men out of British territory. Mohammad's men were concentrating on driving their cattle away and harassing the pursuing British force, whilst avoiding a formal fixed engagement, and it was one such encounter on July 17th that brings Captain Duncan Friederichs into the story.

A Royal Engineer, born in 1869, Friederichs was the son of Hugo,from Oldenburg in North-West Germany, who had come to Britain as a banker's clerk. As Duncan rode out in the Ogadan his mother, Isabella, was a widow, living in the rectory at Acton Scott in Shropshire, with his brother, Charles Gustave, the vicar of nearby Eaton-under-Heywood. The contrast could hardly be more stark between St. Ediths, on the wooded lower slopes of Wenlock Edge, and the undulating rocky sandhills Duncan rode towards that day, winding his way between clumps of thorny scrub. Duncan had experienced desert warfare before, having fought at Omdurman, but that was a pitched battle against men carrying swords and spears. This wasn't.

Over the sandhills Mohammad and his men were moving out of British territory, with their families and their herds. On one of those ridges, concealed in the scrub, lay a row of his riflemen, guarding the retreat. As Friederichs and his men drew close the hidden riflemen opened fire, the British turned to move out of range, but an NCO was hit, and fell to the ground. Friederichs turned to help him, but he too was hit, and his wound was fatal. Swayne realised what was happening and sent out more troops, and the riflemen vanished away after their leader. Too late for Friederichs, who was buried where he fell, the last victim of the First Somaliland Campaign. He was the last because Swayne, fearing for his depleted water supplies, decided he could no longer pursue Mohammad. With a sort-of victory secured he returned to Burao. The use of the word "First" gives an idea of how much of a victory it was. The 'Mad' Mullah would be back, and there would be more than one British grave left in the desert.

Colonel Eric Swayne went on to become Governor of British Honduras, retiring to Pucklechurch in Gloucestershire, where he died in 1929, in his mid-sixties. The last de Sausmarez to live at East Molesey Lodge was Lionel's sister, Frances. After she died the house was sold, and then demolished in 1930. The ancestral home on Guernsey is still in the family; at the time of writing, Sausmarez Manor is the only stately home on the island open to visitors. Lionel is commemorated on the family gravestone in Molesey Cemetery, and also on a memorial at Sandhurst. Duncan Friederich's memorial is in the church at Acton Scott in Shropshire, where the only things the local riflemen shoot are game birds.

Sources

Photo

Ogadan Desert - Gennady Shkliar

de Sausmarez Grave - by Julia&keld from www.findagrave.com

Memorial to Captain Duncan Friederichs - courtesy of Suzanne Stirke

Military

glosters.tripod.com/somali.htm

www.somalinet.com

www.kaiserscross.com

In Pursuit of the Mad Mullah: Service and Sport in the Somali Protectorate - Captain Malcolm McNeill, DSO, C. Arthur Pearson, London, 1902

Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland: Betrayal and Redemption - Roy Irons, Pen and Sword, 2013

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

moleseyhistory.co.uk

© Jon Dewhirst 2019

Photo

Ogadan Desert - Gennady Shkliar

de Sausmarez Grave - by Julia&keld from www.findagrave.com

Memorial to Captain Duncan Friederichs - courtesy of Suzanne Stirke

Military

glosters.tripod.com/somali.htm

www.somalinet.com

www.kaiserscross.com

In Pursuit of the Mad Mullah: Service and Sport in the Somali Protectorate - Captain Malcolm McNeill, DSO, C. Arthur Pearson, London, 1902

Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland: Betrayal and Redemption - Roy Irons, Pen and Sword, 2013

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

moleseyhistory.co.uk

© Jon Dewhirst 2019