BEAU GESTE

MAHDIST WARS, SUDAN, 1893

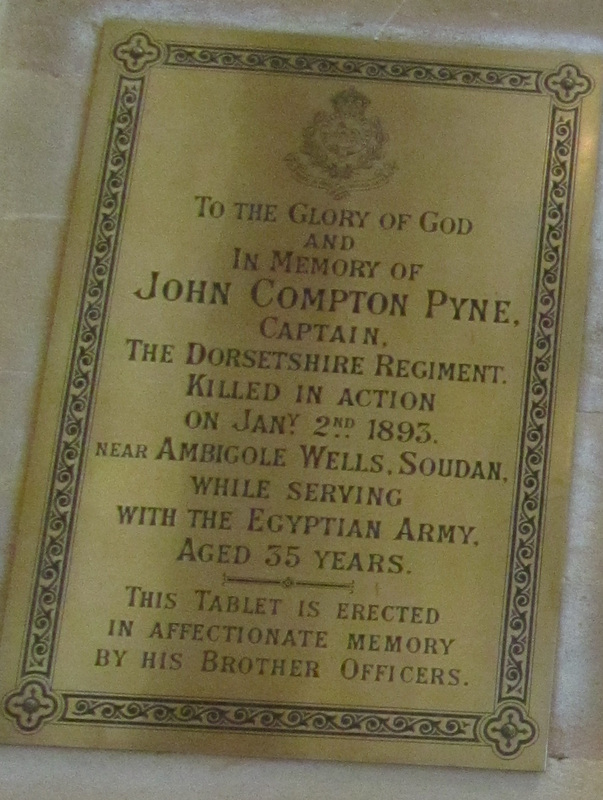

Captain John Compton Pyne, Dorsetshire Regiment

Sherborne Abbey, Sherborne, Dorset

The Man

Ambikol is a town on the banks of the Nile in Northern Sudan. In the late 19th Century it was known as Ambigole Wells, and was the site of a small fort placed there to defend the railway being built by the Egyptians south from Wadi Halfa.

West Acre is a small village in North Norfolk, on a Roman road running to a ford over the River Nar. The village is the site of a ruined Augustinian priory, and it is probable that its only connection with Ambikol lies with Captain John Compton Pyne, who was born in West Acre, but killed at the fort in Ambigole Wells.

Like many of those whose stories are told on this site John Compton Pyne was the son of a Church of England vicar, but from a military background – Lord Kitchener was his cousin.

His father, Edward Manners Dillman Pyne, appears to have been rector of a number of Norfolk parishes, and had enough income to send his son to Uppingham School, and thence to Sandhurst, from where he passed out First in his year, destined for great things. He joined the 54th Regiment as a lieutenant in 1881, the year that the regiment was renamed as the Dorsetshire Regiment. He was clearly both adventurous and talented; in 1884 he persuaded his superiors to grant him leave to travel through Persia on foot, earning money from his violin as he went (echoes of Laurie Lee in Spain fifty years later, as told in ‘As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning’). He was also an artist, and a number of his sketches can be viewed today in the Devonshire & Dorset Museum in Dorchester.

Promoted to Captain in 1885 Pyne saw action in Afghanistan, and then in 1892 was attached to the Egyptian Army Intelligence Unit, with the rank of Bimbashi, the equivalent of Major.

This needs explaining.

The Background

In 1821 Egypt, under its Khedive, Muhammad Ali, invaded Sudan. Although nominally under Ottoman rule Egypt was governed as a virtually independent entity (see The Oriental Crisis of 1840), and Sudan was just part of the Khedive’s expansionist policy, which was continued by his successors. The Egyptians imposed taxes on the Sudanese, but did not interfere with the main money-making activities, especially the slave trade.

From 1869 however the situation changed. In that year the Suez Canal opened, and its importance for Britain as a quick route to India and Australia led to Britain becoming increasingly involved in Egyptian affairs. This culminated in 1879 with a revolt inside Egypt against the corruption of the then-ruler, Tewfik, and against the growing European influence in internal affairs. The revolt was put down with British and French military assistance, but a weakened Egyptian government continued to fail, and in 1882 the British assumed control in everything but name, leaving Tewfik in place but with Britain in charge.

As can be seen elsewhere (Gambia and East Africa) the British could not leave the slave trade unmolested, and so under pressure the Egyptian officials and troops in Sudan began to harass the region’s slave traders, who were the country’s richest and most influential people; most influential apart from Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, an Islamic preacher known as The Mahdi (translated as 'Guided One'). His appearance was a predictable reaction to the oppressive and interfering Egyptian presence in the country, and to the growing Christian influence, and with the backing of the slavers he led a nationalist Islamic backlash, with massive popular support. In 1881 he announced the Mahddiya, a jihad aimed at ejecting the Egyptians and Europeans out of Sudan and creating a Sharia law state.

In 1882 a British-led Egyptian army force of nine thousand men was defeated by the Mahdi’s forces at the Battle of Al Ubbayid. The Mahdists captured other important towns, and in 1883 another large Egyptian force, led by a former Indian Army officer named William Hickes, was obliterated at the Battle of El Obeid. The British viewed Sudan as a sideshow to the main concerns in Egypt, and so ordered the removal of all Egyptian troops from the country, retaining control only of key ports on the coast and on the Nile. This is where Gordon of Khartoum comes in. He was sent to Khartoum to organise the evacuations, and it was his failure to do so that led to his iconic death there in January 1885.

Although the Mahdi himself died in June of that year the Mahdist control of the country, under the three Caliphs who together succeeded the Mahdi, continued to spread, and by the end of 1885 only Sawakin on the coast and Wadi Halfa on the Nile in the north remained in Egyptian hands, both garrison towns too strong for the Mahdists to take.

And that was the way things stayed for the rest of the decade. The Mahdist rebellion against the occupying Egyptian forces had been successful, and they even attempted to expand their influence. In 1887 Mahdist forces invaded Ethiopia, in 1889 they invaded Egypt until being defeated at the Battle of Tushkah, and in 1893 they attempted to take part of Italian-controlled Eritrea.

The Action

1893 brings us back to John Compton Pyne. By the early 1890s Sudan had become more important to the British, mainly because the British were wary of encroachments into the region by other European powers: Germany and Belgium to the south; Italy to the east; France to the west. Egyptian army units were sent back into Sudan, particularly along the railway that was being built beside the Nile south-west from Wadi Halfa, where a series of forts were erected to safeguard the line. One of those forts was at Ambigole Wells.

In January 1893 Pyne was stationed at the fort with a small contingement of men when they were attacked by a large force of Mahdists. The fort’s defences proved inadequate, and the defenders were soon overwhelmed. All were killed. Pyne’s head was severed from his body and taken to Khartoum, where it was placed over one of the city gates.

When mourning his untimely death Kitchener wrote, 'Captain Pyne was one of the most valuable and excellent officers in the Egyptian Army, and there is no doubt that had he been spared his career would have been a brilliant one.' Unfortunately, he wasn’t spared.

Ambikol is a town on the banks of the Nile in Northern Sudan. In the late 19th Century it was known as Ambigole Wells, and was the site of a small fort placed there to defend the railway being built by the Egyptians south from Wadi Halfa.

West Acre is a small village in North Norfolk, on a Roman road running to a ford over the River Nar. The village is the site of a ruined Augustinian priory, and it is probable that its only connection with Ambikol lies with Captain John Compton Pyne, who was born in West Acre, but killed at the fort in Ambigole Wells.

Like many of those whose stories are told on this site John Compton Pyne was the son of a Church of England vicar, but from a military background – Lord Kitchener was his cousin.

His father, Edward Manners Dillman Pyne, appears to have been rector of a number of Norfolk parishes, and had enough income to send his son to Uppingham School, and thence to Sandhurst, from where he passed out First in his year, destined for great things. He joined the 54th Regiment as a lieutenant in 1881, the year that the regiment was renamed as the Dorsetshire Regiment. He was clearly both adventurous and talented; in 1884 he persuaded his superiors to grant him leave to travel through Persia on foot, earning money from his violin as he went (echoes of Laurie Lee in Spain fifty years later, as told in ‘As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning’). He was also an artist, and a number of his sketches can be viewed today in the Devonshire & Dorset Museum in Dorchester.

Promoted to Captain in 1885 Pyne saw action in Afghanistan, and then in 1892 was attached to the Egyptian Army Intelligence Unit, with the rank of Bimbashi, the equivalent of Major.

This needs explaining.

The Background

In 1821 Egypt, under its Khedive, Muhammad Ali, invaded Sudan. Although nominally under Ottoman rule Egypt was governed as a virtually independent entity (see The Oriental Crisis of 1840), and Sudan was just part of the Khedive’s expansionist policy, which was continued by his successors. The Egyptians imposed taxes on the Sudanese, but did not interfere with the main money-making activities, especially the slave trade.

From 1869 however the situation changed. In that year the Suez Canal opened, and its importance for Britain as a quick route to India and Australia led to Britain becoming increasingly involved in Egyptian affairs. This culminated in 1879 with a revolt inside Egypt against the corruption of the then-ruler, Tewfik, and against the growing European influence in internal affairs. The revolt was put down with British and French military assistance, but a weakened Egyptian government continued to fail, and in 1882 the British assumed control in everything but name, leaving Tewfik in place but with Britain in charge.

As can be seen elsewhere (Gambia and East Africa) the British could not leave the slave trade unmolested, and so under pressure the Egyptian officials and troops in Sudan began to harass the region’s slave traders, who were the country’s richest and most influential people; most influential apart from Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, an Islamic preacher known as The Mahdi (translated as 'Guided One'). His appearance was a predictable reaction to the oppressive and interfering Egyptian presence in the country, and to the growing Christian influence, and with the backing of the slavers he led a nationalist Islamic backlash, with massive popular support. In 1881 he announced the Mahddiya, a jihad aimed at ejecting the Egyptians and Europeans out of Sudan and creating a Sharia law state.

In 1882 a British-led Egyptian army force of nine thousand men was defeated by the Mahdi’s forces at the Battle of Al Ubbayid. The Mahdists captured other important towns, and in 1883 another large Egyptian force, led by a former Indian Army officer named William Hickes, was obliterated at the Battle of El Obeid. The British viewed Sudan as a sideshow to the main concerns in Egypt, and so ordered the removal of all Egyptian troops from the country, retaining control only of key ports on the coast and on the Nile. This is where Gordon of Khartoum comes in. He was sent to Khartoum to organise the evacuations, and it was his failure to do so that led to his iconic death there in January 1885.

Although the Mahdi himself died in June of that year the Mahdist control of the country, under the three Caliphs who together succeeded the Mahdi, continued to spread, and by the end of 1885 only Sawakin on the coast and Wadi Halfa on the Nile in the north remained in Egyptian hands, both garrison towns too strong for the Mahdists to take.

And that was the way things stayed for the rest of the decade. The Mahdist rebellion against the occupying Egyptian forces had been successful, and they even attempted to expand their influence. In 1887 Mahdist forces invaded Ethiopia, in 1889 they invaded Egypt until being defeated at the Battle of Tushkah, and in 1893 they attempted to take part of Italian-controlled Eritrea.

The Action

1893 brings us back to John Compton Pyne. By the early 1890s Sudan had become more important to the British, mainly because the British were wary of encroachments into the region by other European powers: Germany and Belgium to the south; Italy to the east; France to the west. Egyptian army units were sent back into Sudan, particularly along the railway that was being built beside the Nile south-west from Wadi Halfa, where a series of forts were erected to safeguard the line. One of those forts was at Ambigole Wells.

In January 1893 Pyne was stationed at the fort with a small contingement of men when they were attacked by a large force of Mahdists. The fort’s defences proved inadequate, and the defenders were soon overwhelmed. All were killed. Pyne’s head was severed from his body and taken to Khartoum, where it was placed over one of the city gates.

When mourning his untimely death Kitchener wrote, 'Captain Pyne was one of the most valuable and excellent officers in the Egyptian Army, and there is no doubt that had he been spared his career would have been a brilliant one.' Unfortunately, he wasn’t spared.

Sources

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2013