Battle of Deeg, India, 1804

Major-General John Henry Fraser

East India Company

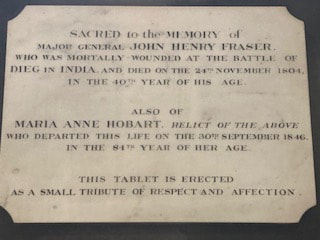

Chichester Cathedral, West Sussex

It is safe to say I had never heard of Deeg before Peter Jones send me the photo of General Fraser's tablet, never mind knowing where it is. In fact it is a small town sixty miles north-west of Agra and one hundred and twenty miles south of Delhi. What on earth was Major-General John Fraser doing dying there?

I have written elsewhere of how the campaigns of Wellesley and Lake successfully defeated the forces of the Maratha Confederacy and sealed the East India Company's control of India. There was not, however, a total capitulation to the Company's demands; one of the leading Maratha princes, Yashwantrao Holkar of Indore, refused to accept the treaties signed by the other Maratha leaders, and so continued to oppose the Company's forces, following a form of guerrilla warfare. He was not alone in this, with, among others, Maharajah Ranjit Singh of Bhuratpore supporting him.

On 13th November 1804, after over a year of guerrilla skirmishes, the British eventually managed to force the Marathas into a formal battle - at Deeg.

Deeg was one of Ranjit Singh's possessions, the site of a splendid palace surrounded by a moated and multi-towered fort. In front of the fort, between a body swamp and a lake, Holkar set two lines of artillery, with a fortified village in front of them. General Fraser decided on a frontal attack, and at first all went well for the British. The village was taken, as was the first line of guns. However, under heavy fire from the second line of artillery the attack faltered. Fraser went forward to rally the troops, and moved to the front to lead the attack. A mistake, although a brave one admittedly. He was shot down, severely injured in the leg. With their general gone the attack faltered and failed. Fraser was carried from the field, and died twelve days after the battle, following the amputation of the shattered limb. Back in Funtington, Sussex, he left his wife, Maria, and six children aged seven to seventeen.

That his decision to attack, although it suited the tenor of the times, may not have been wise may be judged from what happened when General Lake arrived to take command after the abortive battle. Lake decided on a siege of the fort, which began on the 20th, followed on 11th December by artillery shelling, and then finally an assault on a breach in the walls on the 24th. Sensing defeat, the Holkar and Ranjit Singh retreated to the even more formidable defensive fortress of Bharatpore. There they withstood four assaults, which cost thousands of British casualties, until eventually agreeing non-punitive terms.

The British now had peace of a sort, although Holkar remained restless, and would continue to be a threat until his death at the age of thirty-five in 1811. He stands as an example of how difficult it would be for the East India Company to totally subjugate India, and as an example of how people conquered against their will, without their compliance, always find the subsequent occupation difficult to accept. Unless, of course, they can be bought off. Then it is principle against cupidity, and that is a dispiriting thought, for me at least. Holkar was fighting against an occupying force, but his fellow leaders, admittedly after having been defeated in battle, chose not to join him in continuing the struggle. Instead they made deals, which allowed them to keep their wealth, albeit not their power, which went to the East India Company.

And that for me is where the death of General Fraser leaves a bitter taste. If he had been fighting for his country, albeit leading an occupying force, I would find it acceptable, but he was not. He was fighting for a profit-making enterprise, a private company, which in essence makes him mercenary. The more I study the exploits of the East India Company, the more distasteful an enterprise it seems.

I have written elsewhere of how the campaigns of Wellesley and Lake successfully defeated the forces of the Maratha Confederacy and sealed the East India Company's control of India. There was not, however, a total capitulation to the Company's demands; one of the leading Maratha princes, Yashwantrao Holkar of Indore, refused to accept the treaties signed by the other Maratha leaders, and so continued to oppose the Company's forces, following a form of guerrilla warfare. He was not alone in this, with, among others, Maharajah Ranjit Singh of Bhuratpore supporting him.

On 13th November 1804, after over a year of guerrilla skirmishes, the British eventually managed to force the Marathas into a formal battle - at Deeg.

Deeg was one of Ranjit Singh's possessions, the site of a splendid palace surrounded by a moated and multi-towered fort. In front of the fort, between a body swamp and a lake, Holkar set two lines of artillery, with a fortified village in front of them. General Fraser decided on a frontal attack, and at first all went well for the British. The village was taken, as was the first line of guns. However, under heavy fire from the second line of artillery the attack faltered. Fraser went forward to rally the troops, and moved to the front to lead the attack. A mistake, although a brave one admittedly. He was shot down, severely injured in the leg. With their general gone the attack faltered and failed. Fraser was carried from the field, and died twelve days after the battle, following the amputation of the shattered limb. Back in Funtington, Sussex, he left his wife, Maria, and six children aged seven to seventeen.

That his decision to attack, although it suited the tenor of the times, may not have been wise may be judged from what happened when General Lake arrived to take command after the abortive battle. Lake decided on a siege of the fort, which began on the 20th, followed on 11th December by artillery shelling, and then finally an assault on a breach in the walls on the 24th. Sensing defeat, the Holkar and Ranjit Singh retreated to the even more formidable defensive fortress of Bharatpore. There they withstood four assaults, which cost thousands of British casualties, until eventually agreeing non-punitive terms.

The British now had peace of a sort, although Holkar remained restless, and would continue to be a threat until his death at the age of thirty-five in 1811. He stands as an example of how difficult it would be for the East India Company to totally subjugate India, and as an example of how people conquered against their will, without their compliance, always find the subsequent occupation difficult to accept. Unless, of course, they can be bought off. Then it is principle against cupidity, and that is a dispiriting thought, for me at least. Holkar was fighting against an occupying force, but his fellow leaders, admittedly after having been defeated in battle, chose not to join him in continuing the struggle. Instead they made deals, which allowed them to keep their wealth, albeit not their power, which went to the East India Company.

And that for me is where the death of General Fraser leaves a bitter taste. If he had been fighting for his country, albeit leading an occupying force, I would find it acceptable, but he was not. He was fighting for a profit-making enterprise, a private company, which in essence makes him mercenary. The more I study the exploits of the East India Company, the more distasteful an enterprise it seems.

Sources

Tablet from Chichester Cathedral - Peter Jones

Wikipedia

'At the Point of the Bayonet: a Tale of the Mahratta War' - G. A. Henty, Black & Son, London, 1901

'A History of the Mahrattas' - James Grant Duff, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, London, 1826

'The Despatches, Minutes and Correspondence of the Marquess of Wellesley KG during his administration of India Vo. 5' - Marquess Richard Wellesley, Murray, India, 1837

Tablet from Chichester Cathedral - Peter Jones

Wikipedia

'At the Point of the Bayonet: a Tale of the Mahratta War' - G. A. Henty, Black & Son, London, 1901

'A History of the Mahrattas' - James Grant Duff, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, London, 1826

'The Despatches, Minutes and Correspondence of the Marquess of Wellesley KG during his administration of India Vo. 5' - Marquess Richard Wellesley, Murray, India, 1837