FIRST SIKH WAR, PUNJAB, 1845-46

Lieutenant Henry Donnithorne Swettenham, 16th Lancers

St. Mary's, Astbury, Cheshire

Major-General Sir John McCaskill, 3rd Infantry Division

St. Mary Abbot, Kensington

Captain Abel William Dottin Best, 80th Foot

St. Peter's, Leckhampton, Gloucestershire

Lieutenant Octavius Carey, 29th Regiment of Foot

The Town Church, St. Peter Port, Guernsey

Lieutenant James Colebrook Harvey, 39th Foot

St. Mary's, Merton

Lieutenant George C. G. Bythesea, 80th Foot

St. Peter's, Freshford, Somerset

Major-General Sir Robert Henry Dick

Dunkeld Cathedral, Tayside

Lieutenant William Dalgleish Playfair, 33rd Bengal Native Infantry

St. Salvator's Chapel, St. Andrew's

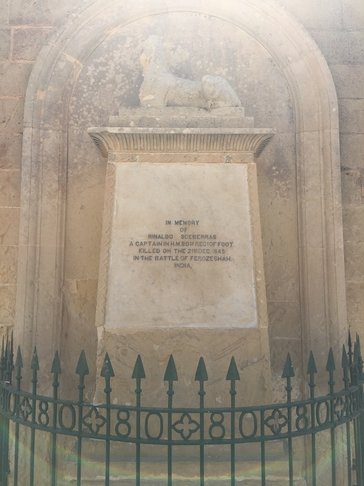

Captain Rinaldo Sceberras, 80th Regiment of Foot

Upper Barrakka Gardens, Valetta, Malta

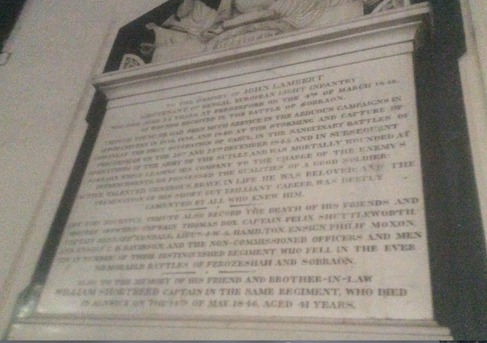

Lieutenant John Lambert, 1st Bengal European Light Infantry

St. Michael's, Alnwick, Northumberland

Captain Charles Clark, 1st Bengal European Light Infantry

St. Peter's, Dorchester, Dorset

The Background

For a tale of duplicity and hypocrisy, brutality and deception, betrayal and sheer bloody-mindedness, it is hard to beat the First Sikh War. Some people somewhere will have behaved with honour and dignity, but they will have been the ones doing the fighting, and even that was accompanied by some stunning savagery. Those responsible for orchestrating the war were outstanding in their cupidity and deceit. Many would say ‘twas ever thus.

The war was against what is known as the Sikh Empire, but the Sikh state as a united military and political entity was a recent phenomenon. In the 18th Century the Sikhs had been under a loose confederation of 12 regions of the Punjab (which covered much of present northern Pakistan, as well as the current Indian Punjab) known as misls, each of which was effectively independent, although they held biennial meetings to discuss legislature and foreign affairs. In the late 1790s things began to change, when Ranjit Singh became Commander of the Sukerchakia misl, and began a campaign to unite them all into a single state, under a single ruler - himself.

Over the following three decades Ranjit successfully extended Sikh rule, control of the Sikh misls being followed by expansion into neighbouring regions, including Kashmir, the areas bordering Afghanistan, and the lands running towards areas controlled by the East India Company, with the River Sutlej functioning as the border with the British. For the latter this was no bad thing. A strong non-hostile state acting as a buffer between them and the instability of Afghanistan was welcomed, and as long as Ranjit Singh was on the throne all was well.

But nobody lives for ever, and when autocrats die they often leave behind a power vacuum ready to be filled with chaos. The Sikh Empire was no exception, not helped by Ranjit having had four wives and eight sons.

The Succession Struggle

Ranjit died in late June 1839, and was succeeded by his fourth son, Kharak Singh. He lasted less than four months. In early October he was dethroned and imprisoned by his own son, Ranjit’s grandson, Nau Nihal Singh. He in turn lasted just over a year.

On 5th November 1840 the deposed Kharak Singh died in his cell in Lahore, probably poisoned. Following his funeral the next day Nau Nihal was passing under one of the city’s gateways when it collapsed on top of him (as gateways do). He died of his injuries, or he may have had them enhanced, and now various power blocs started to maneouvre for position.

When the jockeying for position had ceased the incumbent of the throne was Ranjit’s second son, Sher Singh. He lasted over two years, but he cannot be called successful. His court became known for its extravagant and dissolute lifestyle, and that did not go down well with a major player in the state, in this case an institution, not a person.

The Khalsa was the Sikh army, created by Ranjit along European lines, and honed into an effective and powerful fighting force; hence the success of his campaigns. They were loyal to the crown, whoever wore it, but even loyalty can be stretched too far when soldiers are not being paid; the Khalsa were not, and so felt they were being ignored and insulted by Sher Singh, particularly when so much money was spent so ostentatiously at court. Moreover, they were fighting men, and were used to military success under Ranjit. Since his death the campaigns of conquest had ceased, and the Khalsa were becoming restless, particularly with regard to what they perceived as the growing military threat from the British.

More Complications

In August 1843, after a few months of fighting, the British formally annexed the Province of Sind, which lay to the Punjab’s south. It may just be coincidence that the following month Sher Singh was murdered by one of his cousins, an officer of the Khalsa, and replaced by yet another of Ranjit’s sons, his youngest, Duleep Singh. He was five years old, and his mother, Jind Kaur, became regent, but infants on the throne have never been secure, especially if they have older step-brothers, as Duleep did.

Peshaura Singh was Ranjit’s seventh son, and he developed the backing of dissident elements in the Khalsa and the court. In the summer of 1845 he rebelled and seized the fort at Attock, on the Indus in the north of the Punjab. Duleep’s forces, under the command of the Vizier, Jawahar Singh, who was Jind Kaur’s brother, marched north and put down the rebellion, and on August 30th Peshaura was killed.

With unrest in the Khalsa simmering Jind Kaur and Jawahar arranged a meeting with them. The wisdom of this can be questioned in hindsight, given that as words became heated Jawahar was torn from his mount and hacked to death by the enraged troops, as Jind Kaur and Duleep looked on, unable to intervene. Having killed the man they held responsible for Peshaura Singh’s death the Khalsa’s leaders then quixotically swore their allegiance to Duleep, even though Jind Kaur swore vengeance for the slaying of her brother. She remained as Regent, and two of her faction, Lal Singh and Tej Singh, were appointed Vizier and Commander-in-Chief of the Army respectively.

The stage was now set for conflict. The Khalsa wanted war, and Jind Kaur wanted the Khalsa’s blood, so war it would be, and there was really only one enemy to fight. In anticipation the British sent the Bengal Army under Sir Hugh Gough, accompanied by The Governor-General of Bengal, Sir Henry Hardinge, to the British base at Firozpur (or Ferozepore) on the Sutlej.

On December 11th 1845 the Khalsa crossed the river, and Hardinge declared war. So began what George Macdonald Fraser’s Flashman called “the bloodiest, shortest war ever fought in India”. It was to be a war of battles.

Mudki

The first action was at Mudki (or Moodkee) on the 18th. Having force-marched his troops towards Firozpur, but still eighteen miles short of it, Gough halted in the late afternoon, and his force of just over ten thousand men began to prepare meals. Alerted by the smoke from the fires a Sikh advance guard reported their presence, and the concealed Sikh heavy artillery opened fire. To their credit Gough’s force reacted quickly. He responded with his howitzers (his light guns) and his troops deployed to face Sikh cavalry attacks on both flanks. The Sikh cavalry were of high repute, but in all their campaigns they had never encountered any opposition as experienced and disciplined as the British and East India Army troops, and both attacks were repelled. Gough then sent his light cavalry in to disrupt the Sikh guns, and they did so, albeit taking heavy casualties as they encountered the Sikh infantry. Then Gough sent his infantry in a full-frontal assault.

The division on the right of the attack was of two British regiments, the 9th and 80th Foot, and two regiments of the Bengal Native Infantry, the 26th and the 73rd. Its commander was one of India's more renowned fighting soldiers, a veteran of Indian campaigns since 1806, Sir John McCaskill. When he led his division into the murk of Mudki he was in his sixties, renowned for his part in the retaking of Kabul after the debacle of the First Afghan War, and proud of his reputation for being in front when leading his men into battle. This time he paid for his bravery, as he received a volley of grapeshot in the chest, and was killed instantly, ironically the only officer of his division to die at Mudki. At his death he was already a grandfather and one of his grandchildren was to leave a permanent mark on the sub-continent. Henry Mortimer Durand was the man who negotiated the Durand Line, which still demarcates the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Lieutenant Octavius Carey shouldn’t even have been there. His regiment, the 29th Foot, were not involved, but he had been attached to the 50th, and they were. He was the scion of two established and important Guernsey family, the Careys and the Le Marchants. His father, also Octavius, had reached the rank of Major-General, and was in command of the Cork district in Ireland at his death in 1844. His mother, Dame Harriott Hirzel Carey, lived on in Guernsey until her death in 1877. Octavius was unlucky enough to be one of the officers sent in by Gough to tackle the Sikh infantry at Mudki.

By this stage it was dark, and the battle carries the epithet ‘Midnight Mudki’. The fighting was apparently chaotic, as one can expect when soldiers cannot see what they are doing. After two hours of fighting, with friendly fire a constant threat, the Sikh infantry were eventually driven from the field, fleeing into the jungle. The Sikh casualties were unknown, though estimated to be up to a thousand dead. The British lost just over two hundred, including Octavius Carey. Their corpses were buried on the battlefield.

SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF LIEUT. OCTAVIUS CAREY, OF HER MAJESTY'S 29TH REGT OF FOOT, ELDEST SON OF MAJOR GENERAL SIR OCTAVIUS CAREY, OF THIS ISLAND, HE WAS KILLED ON THE 18TH DECEMBER 1845, IN THE GLORIOUS ACTION OF MOODKEE, ON THE RIVER SUTLEJ, IN THE 26TH YEAR OF HIS AGE. HIS MORTAL REMAINS WERE INTERRED BY HIS BROTHER OFFICERS IN THE MEMORABLE FIELD WHERE HE FELL.

IN MEMORIAM MAJOR-GENERAL SIR JOHN McCASKILL KCB KH. BORN 1781. JOINED THE 3RD SHROPSHIRE REGIMENT 1797. LIEUTENANT-COLONEL 89TH REGIMENT IN 1826. SERVED THROUGHOUT THE MAHRATTA WAR 1817-18 AND THROUGH THE AFGHAN CAMPAIGN OF 1842.COMMANDED THE DETACHED COLUMN WHICH ASSAULTED AND CAPTURED ISTALIF, SEPTEMBER 1842. FELL AT MOODKEE 18TH DECEMBER 1845. THIS TABLET IS ERECTED BY HIS DAUGHTER JESSIE MITCHELL

Ferozeshah

Gough’s troops needed time to recuperate, so he rested for a couple of days, which allowed Lal Singh the opportunity to regroup his forces and fortify his encampment at a village named Ferozeshah. Gough followed him there, and wanted to attack immediately, as he knew Tej Singh was not far away with an even greater force, but Governor Hardinge overruled him, and insisted he wait for the reinforcements that were coming from Ferozipur under General Littler.

When the reinforcements arrived Gough ordered an immediate attack, his artillery beginning firing at half-past three in the afternoon. This was followed up by infantry advances under Littler on the left and General Gilbert on the right flank. Coming under heavy artillery fire Littler charged, but was driven back, with one regiment, the 62nd Foot, losing half its men. It is likely that it was at this point that Littler lost one of his aide-de-camps, Lieutenant James Colebrooke Harvey of the 39th Foot. Harvey was Littler's wife's cousin, member of a Indian army dynasty, the Colebrookes, that produced many colonels and higher ranks. Harvey would probably have joined them had luck been with him. On the right Gilbert’s men broke through, only to be attacked by Sikh cavalry, who were then dramatically dispersed by a much smaller force of the 3rd Light Dragoons. As darkness drew down a reserve division under Sir Harry Smith penetrated the centre of the Sikh lines, but then withdrew as night fell. It was during one of those actions that Captain Rinaldo Sceberras was killed. Men of the 62nd and 80th Foot broke through the Sikh lines, Sceberras seizing the black Sikh standard. He was immediately struck down, as were the two men who followed him. Taking the enemy's standard clearly was not a safe thing to do.

Rinaldo Sceberras was Maltese, the son of a French count who had fought for Napoleon in Egypt and Italy before retiring to Malta. The 80th Foot were the garrison troops on the island in the 1820s, and as soon as Rinaldo was eighteen he persuaded his parents to buy him an ensign's commission in the regiment. The 80th left the Mediterranean in 1830, and Rinaldo was never to see the island or his family again. In 1837 the regiment were posted to Australia, where he married Jane Platt of Morpeth, Sydney. A year later he was sent to India, leaving his wife to become a widow.

When the next day dawned it became evident that the British forces had managed to occupy most of the Sikh camp, including capturing seventy guns, and Gough ordered his troops to press on. By noon Lal Singh’s army had fled, leaving Gough’s troops victorious, but also exhausted, with depleted stocks of food, water and ammunition. Not a good time for Tej Singh to arrive with his fresh troops.

Then the bizarre happened. The Quartermaster, Captain Lumley, apparently suffering from heatstroke and exhaustion, and without seeking permission from Gough, ordered the artillery to go to Ferozipur to seek fresh ammunition, and also sent half the cavalry with it. What was clearly an aberration was apparently taken by Tej Singh as a cunning ploy, an attempt to outflank him, and so, despite the pleadings of his officers, who thought Gough’s force was there for the taking, Tej Singh withdrew, taking his army back over the Sutlej.

Gough came under some criticism for his conduct of these battle. The full-frontal assaults had been successful, but the losses had been great. At Ferozeshah he lost seven hundred men killed and seventeen hundred wounded, losses that many deemed unnecessary. The 9th and 62nd Foot both suffered nearly three hundred casualties, over a quarter of their strength. Of the British regiments even the one which got off the most lightly, the 80th, had eighty-nine casualties, including Captain Abel Best and Lieutenant George Bythesea.

Abel Best was one of six children of a member of a much-maligned section of society, the slave-owning sugar-growers of the Caribbean, in this case Barbados. Despite their wealth (which was large enough to pay for the purchase of Abel's Captaincy in 1841) the family were not blessed with long life. Abel's older brothers, Thomas and John, had both died before the age of forty. Father John Rycroft Best drowned in the RMS Amazon disaster of 1852, mother Catherine (née Devins or de Vins) died at Leckhampton in 1855, and sister Frances Maria Wybault died in London in her fifties in 1857. One sister, Helen, outlived all her siblings by half a century. She married Binny Colvin in 1841, gave birth to six children in India (and all survived), and died in London in 1910. The line and name continued through her children; a Sydney radio-show host today is called Binny Colvin.

George Bythesea was the eldest of five sons of a Somerset clergyman, another George. Four joined the army, and one the navy. Unlike the Best family the Bythesea lived relatively long lives and were relatively successful: Samuel lived in the family home, Freshford Hall near Bath, until 1904; Francis became a Major-General in the 1st Royal Dragoons; John, the naval officer, retired as a Rear-Admiral but has more distinction from being the second person to be awarded the Victoria Cross, gained for bravery in the Baltic Sea during the Crimean War. George did not live to see his brother's glory.

TO THE MEMORY OF LIEUTENANT JAMES COLEBROOKE HARVEY, HM 39th REGIMENT AND AIDE DE CAMP TO MAJOR GENERAL SIR JOHN LITTLER, KCB, WHO WAS KILLED AT THE BATTLE OF FEROZESHAH ON 21st DECEMBER 1845 IN THE 24th YEAR OF HIS AGE

IN MEMORY OF HER YOUNGEST SON, OUR DEAR BROTHER ABEL WILLIAM DOTTIN BEST, CAPTAIN IN HER MAJESTY'S 80th REGIMENT, WHO FELL AT THE BATTLE OF FEROZESHAH ON THE NIGHT OF DECEMBER 21st 1845

IN MEMORY OF GEORGE CHARLES GLOSSOP BYTHESEA OF HER MAJESTY'S 80th REGIMENT KILLED IN ACTION AT FEROZESHAH 1845

ALSO OF THEIR SON CHARLES CLARK CAPTAIN IN THE 1ST BENGAL EUROPEAN REGIMENT WHO DIED OCTOBER 13TH 1846 AGED 37 AFTER PROTRACTED SUFFERING FROM A SEVERE WOUND RECEIVED AT THE BATTLE OF FEROZESHAH. HIS MATERIAL REMAINS ARE DEPOSITED AT SOOBATHOO WHERE OFFICERS OF HIS REGIMENT IN TESTIMONY OF THEIR FRIENDSHIUP AND REGRET HAVE ERECTED A TOMB IN HIS MEMORY

IN MEMORY OF RINALDO SCEBERRAS. A CAPTAIN IN H.M. 80TH REGT OF FOOT. KILLED ON THE 21ST DECEMBER 1845 IN THE BATTHE OF FEROZESHAH, INDIA

Aliwal

No rest for the wicked though. The Khalsa’s main forces may now have been back on their side of the Sutlej, but in the New Year a threat came from a different direction.

Ludhiana lies about 120 miles west of Firozpur, and was an important stopping point for the British supply trains. Word came that a Khalsa force of seven thousand under Ranjodh Singh was moving towards the city, so Sir Harry Smith was sent to intercept him. When Smith arrived at Ludhiana Ranjodh withdrew to Aliwal on the Sutlej, where he established a base to await reinforcements. His force was drawn up along a ridge, with the Sutlej behind them, when Smith attacked on January 28th.

The initial British breakthrough was on their left, where they captured the village of Aliwal and threatened the Sikh centre. As they advanced they exposed their left flank, which was attacked by the enemy cavalry, but the Sikhs were dispersed by the British and Indian horse, including the 16th Lancers. The 16th were to distinguish themselves that day, for as the Sikh infantry looked likely to repulse the British assault the 16th charged them. Infantry formed in squares, as the Sikhs were, are designed to repel cavalry charges, but in this case the 16th broke the squares, allowing the British infantry the opportunity to push through, and turning the Sikh army into a disorderly rout.

Sir Harry Smith regarded the victory as “one of the most glorious battles ever fought in India”, as he vanquished a superior force with very few casualties, other than in the 16th Lancers. They lost one hundred and forty-four out of three hundred men, and one of them was Lieutenant Henry Swetenham. He was from a Cheshire family with an ancestral home at Somerford Booths Hall near Congleton in Cheshire, but many of the previous generation had moved to, and died in, India. Henry himself was born in Fatehgarh, and it is possible that he never actually saw the church in Astbury that contains his memorial, nor visit the house that remained in his family until the 1930s. The early 17th century building is still there, Grade II Listed.

No rest for the wicked though. The Khalsa’s main forces may now have been back on their side of the Sutlej, but in the New Year a threat came from a different direction.

Ludhiana lies about 120 miles west of Firozpur, and was an important stopping point for the British supply trains. Word came that a Khalsa force of seven thousand under Ranjodh Singh was moving towards the city, so Sir Harry Smith was sent to intercept him. When Smith arrived at Ludhiana Ranjodh withdrew to Aliwal on the Sutlej, where he established a base to await reinforcements. His force was drawn up along a ridge, with the Sutlej behind them, when Smith attacked on January 28th.

The initial British breakthrough was on their left, where they captured the village of Aliwal and threatened the Sikh centre. As they advanced they exposed their left flank, which was attacked by the enemy cavalry, but the Sikhs were dispersed by the British and Indian horse, including the 16th Lancers. The 16th were to distinguish themselves that day, for as the Sikh infantry looked likely to repulse the British assault the 16th charged them. Infantry formed in squares, as the Sikhs were, are designed to repel cavalry charges, but in this case the 16th broke the squares, allowing the British infantry the opportunity to push through, and turning the Sikh army into a disorderly rout.

Sir Harry Smith regarded the victory as “one of the most glorious battles ever fought in India”, as he vanquished a superior force with very few casualties, other than in the 16th Lancers. They lost one hundred and forty-four out of three hundred men, and one of them was Lieutenant Henry Swetenham. He was from a Cheshire family with an ancestral home at Somerford Booths Hall near Congleton in Cheshire, but many of the previous generation had moved to, and died in, India. Henry himself was born in Fatehgarh, and it is possible that he never actually saw the church in Astbury that contains his memorial, nor visit the house that remained in his family until the 1930s. The early 17th century building is still there, Grade II Listed.

IN MEMORY OF HENRY DONNITHORNE SWETENHAM, A LIEUT IN H.M. XVITH LANCERS, SON OF HENRY SWETENHAM OF THE BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE AND OF AGNES DONNITHORNE HIS WIFE, GRANDSON OF ROGER SWETENHAM ESQ. OF SOMERFORD BOOTHS IN THE COUNTY OF CHESTER. HE WAS KILLED IN A CHARGE AT THE BATTLE OF ALEEWAL ACTING THE PART OF A GOOD SOLDIER IN FRONT OF A SQUADRON OF HIS REGIMENT ON THE 28TH JANUARY IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1846 AGED 27 YEARS. "IF I FALL, I FALL, I TRUST AS A CHRISTIAN SOLDIER IN THE FULL HOPE OF A RESURRECTION TO A HAPPY LIFE, THROUGH JESUS CHRIST MY SAVIOUR."

St. Mary's, Astbury

Sobraon

The final, decisive, battle, the fourth in under two months, took place on February 10th at Sobraon. The Sikhs had again crossed the Sutlej, and had entrenched their forces in fortifications, with one pontoon bridge connecting the two banks. Following the pattern of the previous engagements the battle started with exchanges of artillery fire, before the British attacked with cavalry on the flanks and infantry in the centre. Again the Sikhs defended stubbornly, but yet again the British broke through and forced their enemy back. That one pontoon bridge now proved insufficient. With the river swollen by three days of heavy rain, the bridge, bearing the unexpected weight of a retreating army, collapsed, leaving almost twenty thousand Khalsa trapped between the river and the advancing British. What followed was a slaughter. Despite their fighting resistance and determined counter-attacks, with very few surrendering, the Sikhs were overwhelmed. Those that tried to swim across were either swept away by the current or shot in the water as the British turned their guns on the river. Few of the trapped Khalsa troops survived; following the savagery of the previous battles, the British troops were unwilling to take prisoners.

During those attacks Major-General Robert Dick, Lieutenant William Playfair and Lieutenant John Lambert were all killed. General Dick had only just succeeded General McCaskill in charge of the 3rd Infantry Brigade following the latter's death at Mudki. He had already led one division of his brigade on the charge, and was leading the second when he was shot down. He was in his sixties, a landowner from Tullimet in Perthshire. Lieutenant Playfair was also from a Perthshire family, his father an East India Company army officer (the plaque in St. Andrew's is because his mother was from Scotscraig in that town). John Lambert was the son of an Alnwick solicitor, and his brother George was also at Sobraon. John was yet another officer to be killed leading his men in a charge; these officers certainly can't be accused of not leading from the front. George went on to be made a General in 1869. Another brother was to die at the Storming of Namtow in 1858.

To the Memory of John Lambert, Lieutenant, 1st Bengal European Light Infantry,

who died aged 24 years at Ferozepore on the 4th March, 1846, of wounds received

in the Battle of Sobraon

Sacred to the memory of Major-General Sir Robert Henry Dick KCB KCH who after distinguished service in the Peninsula in the command of a Light Battalion and at Waterloo with the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment fell mortally wounded whilst leading the 3rd Division of the Army of the Sutledge to the attack on the Seikh entrenched camp at Sobraon on 10 February 1846. The officers who had the honour of serving under him in his last battle and other friends in Her Majesty's and the Honourable East India Company's Service in Bengal have caused this monument to be placed in his parish church

TO THE MEMORY OF WILLIAM DALGLEISH PLAYFAIR, LIEUTENANT IN THE THIRTY-THIRD REGIMENT BENGAL NATIVE INFANTRY, WHO, ON THE 16TH FEBRUARY, 1846, IN THE MEMORABLE BATTLE OF SOBRAON, WHILE GALLANTLY LEADING HIS COMPANY IN THE ATTACK MADE BY SIR ROBERT DICK'S DIVISION ON THE RIGHT OF THE SIKH INTRENCHMENTS, FELL MORTALLY WOUNDED, IN THE 25TH YEAR OF HIS AGE. THIS TABLET WAS ERECTED BY HIS BROTHER OFFICERS, TO WHOM HE WAS ENDEARED BY HIS AMIABLE DISPOSITION AND STERLING CHARACTER. HIS MORTAL REMAINS LIE NEAR THE FIELD OF BATTLE, IN A SOLDIER'S GRAVE UNMARKED AND NOW UNKNOWN.

Aftermath

With their army shattered the Sikhs now had to sue for peace. Duleep Singh retained the throne, and Jind Kaur her regency, but the British now held the influence. The land between the Sutlej and the Chenab rivers was ceded to the East India Company, and a British Resident was placed in Lahore, with subordinates in other Punjab cities. The Sikh kingdom was still nominally independent, but in reality the British were in command.

The British took the victory but the campaign left a number of questions:

· Why did Tej Singh and Lal Singh divide their forces before the battle of Mookjee?

· Once they had split why did Tej not attack an outnumbered Littler in Firozpur, instead of just staying

inactive?

· Why did Tej Singh so eagerly refuse to attack after Ferozeshah, despite his officers’ pleadings?

· Why was there just the one pontoon bridge at Sobraon, when the Sikhs had enough time to build more?

· Were the Khalsa betrayed by their own leaders?

The suspicion has to be that Jind had had her vengeance.

Sources

Photos

Battle of Mudki, by Henry Martens, 1849

The Charge of the 16th Lancers at Aliwal - from Wikimedia Commons, from Donald Featherstone, Victorian colonial warfare - India, Blandford, 1993

St. Peter Port Church - by Alan Ford, from Wikimedia Commons

Memorial to Rinaldo Sceberras - many thanks to Mike Freel

Photo of Astbury Church and Astbury Village - by Dan Carter, from Wikimedia Commons

Military

Online

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Anglo-Sikh_War

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranjit_Singh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mudki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ferozeshah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_aliwal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_sobraon

http://www.indianetzone.com/50/battle_mudki.htm

www.thepeerage.com

Times of Malta 14th December 2014 'A Maltese Officer's death in India' - article by Dennis Darmanin

Flashman and the Mountain of Light - George Macdonald Fraser (Harvill, 1990)

Special Forces Heroes (Michael Ashcroft, Hashette UK, 2012)

Geneology

www.ancestry.co.uk

http://www.qlinks.net/FamilyHistory/swetenham.html

http://www.careyroots.com/e43.html

www.freepages.family.rootsweb.ancestry.com

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2013

St. Mary's, Astbury

Sobraon

The final, decisive, battle, the fourth in under two months, took place on February 10th at Sobraon. The Sikhs had again crossed the Sutlej, and had entrenched their forces in fortifications, with one pontoon bridge connecting the two banks. Following the pattern of the previous engagements the battle started with exchanges of artillery fire, before the British attacked with cavalry on the flanks and infantry in the centre. Again the Sikhs defended stubbornly, but yet again the British broke through and forced their enemy back. That one pontoon bridge now proved insufficient. With the river swollen by three days of heavy rain, the bridge, bearing the unexpected weight of a retreating army, collapsed, leaving almost twenty thousand Khalsa trapped between the river and the advancing British. What followed was a slaughter. Despite their fighting resistance and determined counter-attacks, with very few surrendering, the Sikhs were overwhelmed. Those that tried to swim across were either swept away by the current or shot in the water as the British turned their guns on the river. Few of the trapped Khalsa troops survived; following the savagery of the previous battles, the British troops were unwilling to take prisoners.

During those attacks Major-General Robert Dick, Lieutenant William Playfair and Lieutenant John Lambert were all killed. General Dick had only just succeeded General McCaskill in charge of the 3rd Infantry Brigade following the latter's death at Mudki. He had already led one division of his brigade on the charge, and was leading the second when he was shot down. He was in his sixties, a landowner from Tullimet in Perthshire. Lieutenant Playfair was also from a Perthshire family, his father an East India Company army officer (the plaque in St. Andrew's is because his mother was from Scotscraig in that town). John Lambert was the son of an Alnwick solicitor, and his brother George was also at Sobraon. John was yet another officer to be killed leading his men in a charge; these officers certainly can't be accused of not leading from the front. George went on to be made a General in 1869. Another brother was to die at the Storming of Namtow in 1858.

To the Memory of John Lambert, Lieutenant, 1st Bengal European Light Infantry,

who died aged 24 years at Ferozepore on the 4th March, 1846, of wounds received

in the Battle of Sobraon

Sacred to the memory of Major-General Sir Robert Henry Dick KCB KCH who after distinguished service in the Peninsula in the command of a Light Battalion and at Waterloo with the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment fell mortally wounded whilst leading the 3rd Division of the Army of the Sutledge to the attack on the Seikh entrenched camp at Sobraon on 10 February 1846. The officers who had the honour of serving under him in his last battle and other friends in Her Majesty's and the Honourable East India Company's Service in Bengal have caused this monument to be placed in his parish church

TO THE MEMORY OF WILLIAM DALGLEISH PLAYFAIR, LIEUTENANT IN THE THIRTY-THIRD REGIMENT BENGAL NATIVE INFANTRY, WHO, ON THE 16TH FEBRUARY, 1846, IN THE MEMORABLE BATTLE OF SOBRAON, WHILE GALLANTLY LEADING HIS COMPANY IN THE ATTACK MADE BY SIR ROBERT DICK'S DIVISION ON THE RIGHT OF THE SIKH INTRENCHMENTS, FELL MORTALLY WOUNDED, IN THE 25TH YEAR OF HIS AGE. THIS TABLET WAS ERECTED BY HIS BROTHER OFFICERS, TO WHOM HE WAS ENDEARED BY HIS AMIABLE DISPOSITION AND STERLING CHARACTER. HIS MORTAL REMAINS LIE NEAR THE FIELD OF BATTLE, IN A SOLDIER'S GRAVE UNMARKED AND NOW UNKNOWN.

Aftermath

With their army shattered the Sikhs now had to sue for peace. Duleep Singh retained the throne, and Jind Kaur her regency, but the British now held the influence. The land between the Sutlej and the Chenab rivers was ceded to the East India Company, and a British Resident was placed in Lahore, with subordinates in other Punjab cities. The Sikh kingdom was still nominally independent, but in reality the British were in command.

The British took the victory but the campaign left a number of questions:

· Why did Tej Singh and Lal Singh divide their forces before the battle of Mookjee?

· Once they had split why did Tej not attack an outnumbered Littler in Firozpur, instead of just staying

inactive?

· Why did Tej Singh so eagerly refuse to attack after Ferozeshah, despite his officers’ pleadings?

· Why was there just the one pontoon bridge at Sobraon, when the Sikhs had enough time to build more?

· Were the Khalsa betrayed by their own leaders?

The suspicion has to be that Jind had had her vengeance.

Sources

Photos

Battle of Mudki, by Henry Martens, 1849

The Charge of the 16th Lancers at Aliwal - from Wikimedia Commons, from Donald Featherstone, Victorian colonial warfare - India, Blandford, 1993

St. Peter Port Church - by Alan Ford, from Wikimedia Commons

Memorial to Rinaldo Sceberras - many thanks to Mike Freel

Photo of Astbury Church and Astbury Village - by Dan Carter, from Wikimedia Commons

Military

Online

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Anglo-Sikh_War

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranjit_Singh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mudki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ferozeshah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_aliwal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_sobraon

http://www.indianetzone.com/50/battle_mudki.htm

www.thepeerage.com

Times of Malta 14th December 2014 'A Maltese Officer's death in India' - article by Dennis Darmanin

Flashman and the Mountain of Light - George Macdonald Fraser (Harvill, 1990)

Special Forces Heroes (Michael Ashcroft, Hashette UK, 2012)

Geneology

www.ancestry.co.uk

http://www.qlinks.net/FamilyHistory/swetenham.html

http://www.careyroots.com/e43.html

www.freepages.family.rootsweb.ancestry.com

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2013