BAILEY'S GRAVE & AUTA'S CAVE:

EIGHTH XHOSA WAR, SOUTH AFRICA, 1852-53

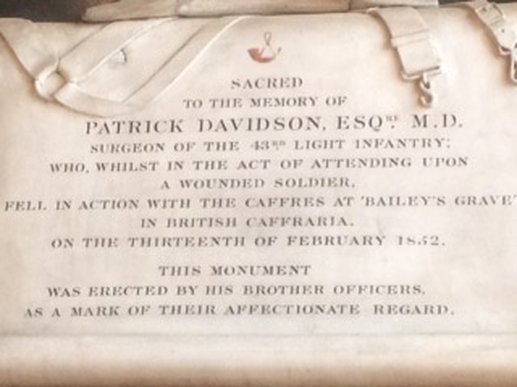

Surgeon Patrick Davidson, 43rd Light Infantry

St. John's Kirk, Perth, Scotland

Captain Owen Arthur Ormsby-Gore, 43rd Light Infantry

St. Oswald's, Oswestry, Shropshire

British Imperial troops attempting to storm the Amatola Fastnesses

British Imperial troops attempting to storm the Amatola Fastnesses

The Man

When 18 year-old Owen Arthur Ormsby-Gore had an ensignship purchased for him in the 43rd Regiment of Foot in 1838 he was going against the family trend. His father, William Ormsby-Gore (plain Gore before his marriage to Mary-Jane Ormsby) was M.P. for North Shropshire, having previously represented Co. Leitrim, and, to complete a trio of countries, Caernarvonshire, which was now represented by Owen’s older brother, John Ralph. Within a few years the other son, William, was to become member for Co. Sligo. Owen, however, clearly preferred the active life, and so joined the 43rd, the Monmouthshire, Regiment.

The regiment was in action in Canada until 1846, with Owen purchasing his lieutenancy in 1841, before returning to England, and then Ireland. In 1851, when he gained his captaincy, it was posted to South Africa, part of the reinforcements requested by the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Harry Smith, as he struggled to subdue a rebellion by the major people of the region, the Xhosa - although I suspect they would not have regarded it as a rebellion. The conflict is now known as the 8th Xhosa War, one of a series known also as the Cape Frontier Wars or, more derogatively, using the contemporary term, the Kaffir Wars.

The Background

The implication that these wars were a series of British-Xhosa struggles is misleading. The first three involved various Xhosa tribes and the Dutch, and later ones also involved settlers, both British and Boer, Khoikoi tribes (at the time also referred to as the Hottentots), and the Fengu people, tribes driven west by the Zulu invasion of what is now Natal. Moreover, at least two of the wars began as civil wars between different Xhosa tribes, throughout some Xhosa remained friendly to the British, and many Khoikoi were members of the Cape Frontier Force. The net result of all the fighting was that over a period of fifty years the Xhosa were driven steadily east and northwards for hundreds of miles, their territory limited by a series of rivers, each more distant than the last – the Fish or Great Vis, the Keiskamma, the Kat, and the Kei. By 1850 many of their former lands were settled and farmed by Boers, British settlers and incoming pro-British Fengu.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the Xhosa became restless when, in June 1850, in the midst of drought and a severe winter, Sir Harry Smith decided to create more land for settlers by displacing those Xhosa living along the Kat River in the north-east of the colony. Smith’s policy imagined the displaced people moving to designated areas or into the towns, where they could provide a ready labour force. Instead, inspired by a preacher named Mianjeni who advocated opposition to the British, they congregated in the frontier tribal areas, and were joined by others who began to leave the colony and the towns. In December Smith, believing, probably correctly, that a leading Xhosa chief, Sandile, was supporting Mianjeni, decided to depose and outlaw him. A few days later a British column was ambushed and put to flight, and settlements and farms throughout the border regions were attacked. The war had begun.

The Action

Initially the Xhosa, who were also joined by many Khoikoi, including deserters from the Frontier Force, had a number of military successes, but gradually the British, having summoned reinforcements, fought back and regained a measure of control. Large groups of Xhosa, however, remained at large, and for the next two years waged an effective guerrilla campaign. Basing themselves in the remote mountain regions and the forested river valleys they severed the main communication routes, making movement between the various settlements dangerous and difficult, and forcing many farmers to abandon their properties.

By early 1852 Smith appeared to be making no progress, stuck in stalemate, and the British Government decided to replace him, suspecting that in many ways his unbending approach had hardly alleviated the situation (he issued a proclamation to settlers urging them to “exterminate these barbarous savages”, and was witnessed “placing his foot on the neck of the Xhosa ruler and proclaiming 'I am your Paramount Chief, and the kaffirs are my dogs'").

He was replaced by General George Cathcart, a Waterloo veteran, who had been Deputy-Lieutenant of the Tower of London until a few months previously. He arrived at the end of March 1852 to find a chaotic situation.

It was shortly before Cathcart's arrival that the 43rd Light Infantry were involved in an action at somewhere known as Bailey's Grave. Several of the regiment's men died, including the surgeon, Patrick Davidson, killed as he was taking dressing from his saddle-bag. He was shot twice through the forehead by two Khoikoi deserters from the Cape Frontier Force. Probably a member of a notable Perth family, in some sources he is mistakenly ranked as Sergeant Davidson. He had clearly made the decision to make his career as an army surgeon; his first appointment as Assistant-Surgeon had been with the 70th Foot, with his promotion to Surgeon coming in October, 1846.

The outlawed chief, Sandile, had avoided capture and was free to be the figurehead of the resistance. The Paramount Chief, Kreili, remained over the Kei River, theoretically uninvolved, although he was in dispute with the Cape Government as they were demanding compensation for all the losses suffered by the settlers from Xhosa raids, and Kreili was refusing to accept responsibility. In the Kroome Mountains, between the towns of Adelaide and Fort Beaufort, the Xhosa chief Macomo and the Khoikoi chief Quasha had joined forces and were raiding incessantly. To the north the tribes under Chief Maphasa were pillaging the areas around Cradock, Albert and North Victoria. In the south tribal chiefs under the strategic command of Seyolo were, with Khoikoi support, raiding the Keiskamma and Fish River lands, and had severed communications between the major settlements of Grahamstown and King William’s Town, while from hideouts in the Amatola Hills a number of minor chiefs were raiding and stealing cattle. It was to this latter area that Lieutenant-Colonel William Eyre was sent, in early April, with a column which included a company of the 45th Foot led by Captain Owen Ormsby-Gore.

The British were now pursuing a scorched-earth policy when patrolling, destroying any villages and crops found, and confiscating as many cattle and horses as possible. One minor chief, Auta, had his base in a mountain cave complex which was discovered by Eyre’s men, who took away 800 cattle and 15 horses. Auta’s men did not just hide away however, and put up what was described as “a desperate fight” during which the British suffered one fatality - Captain Ormsby-Gore. Fighting at the head of his men, the son and brother of three Members of Parliament was killed in what was essentially a fight over stolen cattle, cattle stolen by British forces.

The Aftermath

Cathcart’s strategy was to prove successful in the long term. He laid his initial emphasis on reopening and maintaining communications with Grahamstown, thus placing pressure on Seyolo’s forces in the south, and consequently the chief surrendered, his tribal lands being ceded to the Fengu tribes who had supported the Government forces. In August, with Paramount Chief Krieili still refusing to accede to compensation demands, Cathcart authorized the dispatch of a raid over the Kei which returned with over ten thousand Xhosa cattle.

In September operations were launched in the Kroome Hills, forcing Macomo and Quasha out of their fastness. Macomo fled to the Amatolas, where Satale was also sequestered, only to encounter the operations of Lieutenant-Colonel Eyre. Macomo and Satale fled over the Kei.

In the north the Government forces eventually caught up with Chief Maphasa, who was killed. His tribe were dispersed, his lands redistributed to a friendly tribe, and settlers were reintroduced into the region.

By March 1853 Cathcart could report that the only resistance left was that of Sandile and his followers, who were at large in an unexplored area on the Kei. Despite opposition from within the colony, which wanted Sandile’s head, Cathcart negotiated his surrender and an amnesty, with the stipulation that his people leave their traditional lands and move to a designated area between the Kei and the Amatola Hills. The war was over, and the Xhosa would now live where they were told, defeated.

Afterwards

Kreili remained Paramount Chief, but his people were devastated by a self-induced famine between 1856 and 1858, when a teenage prophetess, supported by Kreili, induced the Xhosa into slaughtering all their own cattle. Kreili went into exile, and died in 1892.

Sandile was eventually killed in a fight with Fengu troops in 1878, during the 9th Xhosa War. His grave is in the Amatola foothills, about 16km from the town of Stutterheim.

Quahsa was captured near the Kei River, but I have not discovered what happened to him subsequently. Macomo was arrested in 1858, following the mass cattle starvation, and was sentenced to death. This was commuted to 20 years imprisonment with hard labour, which probably means he was sent to Robben Island, just as Nelson Mandela, another Xhosa, was a hundred years later.

George Cathcart was killed leading the British 4th Division during the Battle of Inkerman in the Crimea, while Sir Harry Smith died at home in London in 1860. Owen Ormsby-Gore’s brothers became the first two Barons of Harlech, and the 5th Baron founded Harlech Television, the precursor of what is now ITV Wales – maybe that station should tell Owen’s story.

When 18 year-old Owen Arthur Ormsby-Gore had an ensignship purchased for him in the 43rd Regiment of Foot in 1838 he was going against the family trend. His father, William Ormsby-Gore (plain Gore before his marriage to Mary-Jane Ormsby) was M.P. for North Shropshire, having previously represented Co. Leitrim, and, to complete a trio of countries, Caernarvonshire, which was now represented by Owen’s older brother, John Ralph. Within a few years the other son, William, was to become member for Co. Sligo. Owen, however, clearly preferred the active life, and so joined the 43rd, the Monmouthshire, Regiment.

The regiment was in action in Canada until 1846, with Owen purchasing his lieutenancy in 1841, before returning to England, and then Ireland. In 1851, when he gained his captaincy, it was posted to South Africa, part of the reinforcements requested by the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Harry Smith, as he struggled to subdue a rebellion by the major people of the region, the Xhosa - although I suspect they would not have regarded it as a rebellion. The conflict is now known as the 8th Xhosa War, one of a series known also as the Cape Frontier Wars or, more derogatively, using the contemporary term, the Kaffir Wars.

The Background

The implication that these wars were a series of British-Xhosa struggles is misleading. The first three involved various Xhosa tribes and the Dutch, and later ones also involved settlers, both British and Boer, Khoikoi tribes (at the time also referred to as the Hottentots), and the Fengu people, tribes driven west by the Zulu invasion of what is now Natal. Moreover, at least two of the wars began as civil wars between different Xhosa tribes, throughout some Xhosa remained friendly to the British, and many Khoikoi were members of the Cape Frontier Force. The net result of all the fighting was that over a period of fifty years the Xhosa were driven steadily east and northwards for hundreds of miles, their territory limited by a series of rivers, each more distant than the last – the Fish or Great Vis, the Keiskamma, the Kat, and the Kei. By 1850 many of their former lands were settled and farmed by Boers, British settlers and incoming pro-British Fengu.

It is not surprising, therefore, that the Xhosa became restless when, in June 1850, in the midst of drought and a severe winter, Sir Harry Smith decided to create more land for settlers by displacing those Xhosa living along the Kat River in the north-east of the colony. Smith’s policy imagined the displaced people moving to designated areas or into the towns, where they could provide a ready labour force. Instead, inspired by a preacher named Mianjeni who advocated opposition to the British, they congregated in the frontier tribal areas, and were joined by others who began to leave the colony and the towns. In December Smith, believing, probably correctly, that a leading Xhosa chief, Sandile, was supporting Mianjeni, decided to depose and outlaw him. A few days later a British column was ambushed and put to flight, and settlements and farms throughout the border regions were attacked. The war had begun.

The Action

Initially the Xhosa, who were also joined by many Khoikoi, including deserters from the Frontier Force, had a number of military successes, but gradually the British, having summoned reinforcements, fought back and regained a measure of control. Large groups of Xhosa, however, remained at large, and for the next two years waged an effective guerrilla campaign. Basing themselves in the remote mountain regions and the forested river valleys they severed the main communication routes, making movement between the various settlements dangerous and difficult, and forcing many farmers to abandon their properties.

By early 1852 Smith appeared to be making no progress, stuck in stalemate, and the British Government decided to replace him, suspecting that in many ways his unbending approach had hardly alleviated the situation (he issued a proclamation to settlers urging them to “exterminate these barbarous savages”, and was witnessed “placing his foot on the neck of the Xhosa ruler and proclaiming 'I am your Paramount Chief, and the kaffirs are my dogs'").

He was replaced by General George Cathcart, a Waterloo veteran, who had been Deputy-Lieutenant of the Tower of London until a few months previously. He arrived at the end of March 1852 to find a chaotic situation.

It was shortly before Cathcart's arrival that the 43rd Light Infantry were involved in an action at somewhere known as Bailey's Grave. Several of the regiment's men died, including the surgeon, Patrick Davidson, killed as he was taking dressing from his saddle-bag. He was shot twice through the forehead by two Khoikoi deserters from the Cape Frontier Force. Probably a member of a notable Perth family, in some sources he is mistakenly ranked as Sergeant Davidson. He had clearly made the decision to make his career as an army surgeon; his first appointment as Assistant-Surgeon had been with the 70th Foot, with his promotion to Surgeon coming in October, 1846.

The outlawed chief, Sandile, had avoided capture and was free to be the figurehead of the resistance. The Paramount Chief, Kreili, remained over the Kei River, theoretically uninvolved, although he was in dispute with the Cape Government as they were demanding compensation for all the losses suffered by the settlers from Xhosa raids, and Kreili was refusing to accept responsibility. In the Kroome Mountains, between the towns of Adelaide and Fort Beaufort, the Xhosa chief Macomo and the Khoikoi chief Quasha had joined forces and were raiding incessantly. To the north the tribes under Chief Maphasa were pillaging the areas around Cradock, Albert and North Victoria. In the south tribal chiefs under the strategic command of Seyolo were, with Khoikoi support, raiding the Keiskamma and Fish River lands, and had severed communications between the major settlements of Grahamstown and King William’s Town, while from hideouts in the Amatola Hills a number of minor chiefs were raiding and stealing cattle. It was to this latter area that Lieutenant-Colonel William Eyre was sent, in early April, with a column which included a company of the 45th Foot led by Captain Owen Ormsby-Gore.

The British were now pursuing a scorched-earth policy when patrolling, destroying any villages and crops found, and confiscating as many cattle and horses as possible. One minor chief, Auta, had his base in a mountain cave complex which was discovered by Eyre’s men, who took away 800 cattle and 15 horses. Auta’s men did not just hide away however, and put up what was described as “a desperate fight” during which the British suffered one fatality - Captain Ormsby-Gore. Fighting at the head of his men, the son and brother of three Members of Parliament was killed in what was essentially a fight over stolen cattle, cattle stolen by British forces.

The Aftermath

Cathcart’s strategy was to prove successful in the long term. He laid his initial emphasis on reopening and maintaining communications with Grahamstown, thus placing pressure on Seyolo’s forces in the south, and consequently the chief surrendered, his tribal lands being ceded to the Fengu tribes who had supported the Government forces. In August, with Paramount Chief Krieili still refusing to accede to compensation demands, Cathcart authorized the dispatch of a raid over the Kei which returned with over ten thousand Xhosa cattle.

In September operations were launched in the Kroome Hills, forcing Macomo and Quasha out of their fastness. Macomo fled to the Amatolas, where Satale was also sequestered, only to encounter the operations of Lieutenant-Colonel Eyre. Macomo and Satale fled over the Kei.

In the north the Government forces eventually caught up with Chief Maphasa, who was killed. His tribe were dispersed, his lands redistributed to a friendly tribe, and settlers were reintroduced into the region.

By March 1853 Cathcart could report that the only resistance left was that of Sandile and his followers, who were at large in an unexplored area on the Kei. Despite opposition from within the colony, which wanted Sandile’s head, Cathcart negotiated his surrender and an amnesty, with the stipulation that his people leave their traditional lands and move to a designated area between the Kei and the Amatola Hills. The war was over, and the Xhosa would now live where they were told, defeated.

Afterwards

Kreili remained Paramount Chief, but his people were devastated by a self-induced famine between 1856 and 1858, when a teenage prophetess, supported by Kreili, induced the Xhosa into slaughtering all their own cattle. Kreili went into exile, and died in 1892.

Sandile was eventually killed in a fight with Fengu troops in 1878, during the 9th Xhosa War. His grave is in the Amatola foothills, about 16km from the town of Stutterheim.

Quahsa was captured near the Kei River, but I have not discovered what happened to him subsequently. Macomo was arrested in 1858, following the mass cattle starvation, and was sentenced to death. This was commuted to 20 years imprisonment with hard labour, which probably means he was sent to Robben Island, just as Nelson Mandela, another Xhosa, was a hundred years later.

George Cathcart was killed leading the British 4th Division during the Battle of Inkerman in the Crimea, while Sir Harry Smith died at home in London in 1860. Owen Ormsby-Gore’s brothers became the first two Barons of Harlech, and the 5th Baron founded Harlech Television, the precursor of what is now ITV Wales – maybe that station should tell Owen’s story.

Sacred to the memory of Captain Owen Arthur Ormsby Gore of the 43rd Light Infantry third son of William Ormsby Gore Esq. MP of Porkington, who fell in action with the Caffres at the head of his Company on the sixth of April 1852 at "Atna's Cave" British Caffraria. This monument was erected by his brother officers as a mark of their affectionate regard.

Holy Trinity Church, Oswestry

Holy Trinity Church, Oswestry

Sources

Photos

Mgolombone Sandile, Xhosa Chief - Wikimedia Commons, Cape Colony Archive Project

Portico at Castell Brogyntyn - by Row17, geography.org.uk

Great Chief and military leader Maqoma - Wikimedia Commons, Cape Archives

sketch of British Imperial troops attempting to storm the Amatola Fastness, 16th June 1851 - by Captain W. R. King, from the Cape Colony Archives

St. Oswald's Church, Oswestry - by Alan Myers, www.flickr.com

Memorial to Captain Owen Arthur Ormsby Gore - by Martin Nicholson, from his website Martin Nicholson's Cemetery Project (www.martin-nicholson.info)

Memorial to Surgeon Patrick Davidson - by Peter Jones

Military

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaffir_Wartrove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/12937615

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mgolombane_Sandilehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Harry_Smith

'The United Service Journal, Volume 35', Arthur William Alsager Pollock - available online on googlebooks

'Campaigning in Kaffirland, or Scenes and Adventures in the Kaffir War of 1851-52', William Ross King (London, 1865)

'The Colonial Wars Source Book', Philip J. Haythornthwaite (BCA, London, 1995)

A letter from Hon. Henry William Crosbie, 43rd L.I., quoted in 'Letter from Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. Jarvis, editor of 1st Royal Greenjackets (43rd & 52nd) Chronicle' - Wellcome Library, ref. RAMC/1030/2

'The London Gazette, part 4' (page 3766_ - (T. Neuman, London, 1846)

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.search.knightfrank.co.uk

www.thepeerage.com/p43219.htm

© Jon Dewhirst 2014

Photos

Mgolombone Sandile, Xhosa Chief - Wikimedia Commons, Cape Colony Archive Project

Portico at Castell Brogyntyn - by Row17, geography.org.uk

Great Chief and military leader Maqoma - Wikimedia Commons, Cape Archives

sketch of British Imperial troops attempting to storm the Amatola Fastness, 16th June 1851 - by Captain W. R. King, from the Cape Colony Archives

St. Oswald's Church, Oswestry - by Alan Myers, www.flickr.com

Memorial to Captain Owen Arthur Ormsby Gore - by Martin Nicholson, from his website Martin Nicholson's Cemetery Project (www.martin-nicholson.info)

Memorial to Surgeon Patrick Davidson - by Peter Jones

Military

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaffir_Wartrove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/12937615

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mgolombane_Sandilehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Harry_Smith

'The United Service Journal, Volume 35', Arthur William Alsager Pollock - available online on googlebooks

'Campaigning in Kaffirland, or Scenes and Adventures in the Kaffir War of 1851-52', William Ross King (London, 1865)

'The Colonial Wars Source Book', Philip J. Haythornthwaite (BCA, London, 1995)

A letter from Hon. Henry William Crosbie, 43rd L.I., quoted in 'Letter from Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. Jarvis, editor of 1st Royal Greenjackets (43rd & 52nd) Chronicle' - Wellcome Library, ref. RAMC/1030/2

'The London Gazette, part 4' (page 3766_ - (T. Neuman, London, 1846)

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

www.search.knightfrank.co.uk

www.thepeerage.com/p43219.htm

© Jon Dewhirst 2014