THE KACHIN HILLS, BURMA, 1893

Captain Boyce William Morton, 12th Bengal Infantry

Shrewsbury School Chapel

Cantonment Cemetery, Rangoon, Myanmar

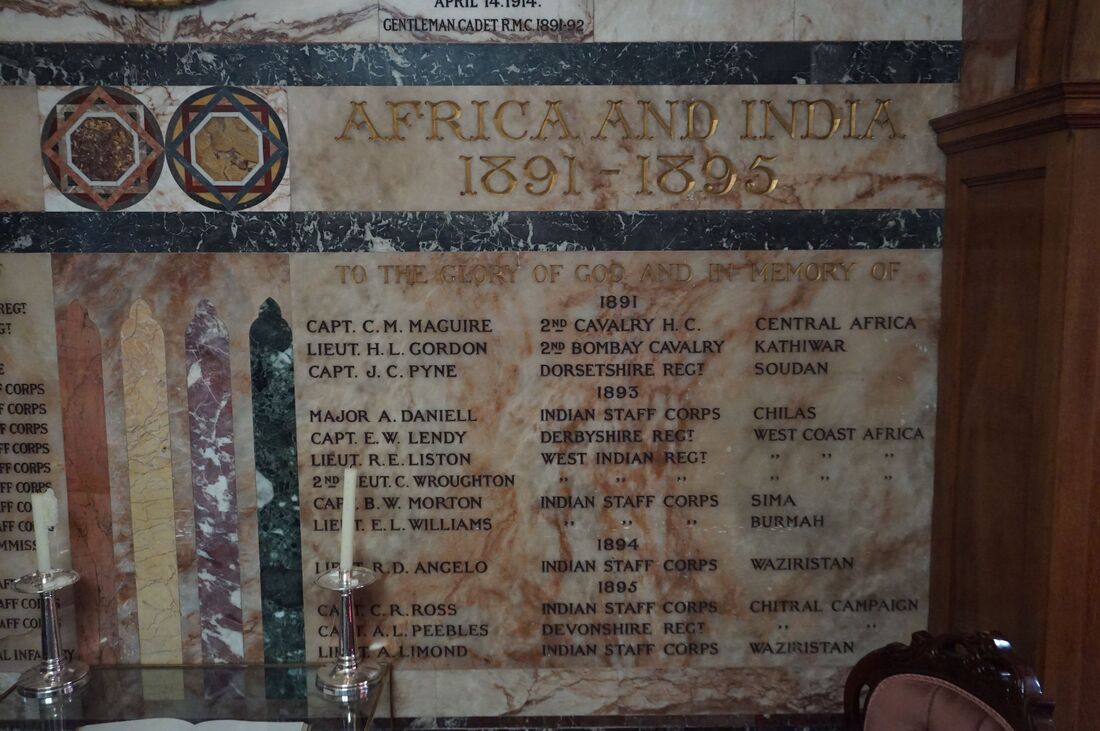

Royal Memorial Chapel, Sandhurst

Delve into the internet and search for “Myanmar”, “rebels” and “Kachin”. There, among the minor news stories swallowed by celebrity gossip, football results and political briefings can be found stories about a state of civil war in Norther Myanmar, where Kachin tribal fighters battle against the military. The Kachin tribes do not like being told what to do, and it was no different towards the close of the 19th Century, which is when a Scots-born member of the Bengal Infantry found himself heading out into the Burmese hills on a mission to bring the tribes east of the Irrawaddy under firmer British control.

Boyce William Morton was born in Edinburgh on Christmas Day, 1858, the son of Boyce William Dunlop Morton and Borders-born Helen Tulloh. Presumably they were in Scotland to be near Helen’s family at the birth of their firstborn, but they did not stay there. In 1861 Helen and the two boys, Boyce and younger brother Robert, were in Torquay, at Heber House in Tormoham. The house appears to be long gone, replaced by residential terraced streets. The Mortons then followed the father of the family to India – son Edward, and daughters Lillie and Amy, were born there in the late 1860s. Boyce senior was working in the Bengal Commissariat at the time, though in 1874 he transferred to the Bengal Staff Corps, with the rank of Lieutenant-General.

Presumably this did not disadvantage his son, as in June 1884 Boyce junior became a lieutenant in the Bengal Staff Corp, joining it from the Norfolk Regiment, with rank backdated three years. He had not been idle since he left Shrewsbury School. He had gone to Sandhurst, then fought in Afghanistan between 1878 and 1880, before being posted to Egypt, where he qualified to receive the Egypt Medal.

However, to gain promotion he must have had to move on, as by 1892 he was in Burma, a Captain in the Military Police, and in June of that year was given military command of a Military Police force to be sent into the Kachin Hills to subjugate the troublesome tribes (elsewhere in these tales is the story of Lieutenant Francis Foster, involved in a similar mission in the Chin Hills in 1890). As with previous expeditions the aim was to disarm the tribesmen and exact a tribute or taxes from them, aims to be facilitated by the construction of roads and the building of stockade camps.

Morton’s force, five hundred and fifty Military Police under Morton’s military command, but also under the civil authority of a Police Superintendent, a Dane called Henry Felix Hertz, was ordered to occupy a village called Sima, in the hills east of the Irrawaddy, and build a camp there. On the 14th of December they began their work, but it was not easy; the camp was fired on every night, with attacks increasing in intensity daily. It must have been a frightening experience – even now a satellite view of Sima shows an open space surrounded by thick forest stretching for miles in each direction. Despite their numbers the force must have felt isolated and under siege – then on January 6th the tribes attempted to turn their siege into a victory.

At dawn they mounted a major attack, from three sides, with over five hundred men, reaching within fifteen metres of the camp’s defences, and surrounding the outlying pickets Morton had established. One picket was especially beleaguered, and Morton left the shelter of the stockade in an effort to organise the picket’s withdrawal. However, like all officers he would have instantly become the full focus of enemy fire, and he was shot in the abdomen, lying wounded and incapacitated on the ground.

At this point Surgeon-Major Owen Edward Pennyfather Lloyd, of the British Army Medical Service, enters the story. He and a bugler, Puna Singh, along with the surviving members of the retreating picket, tried to rescue Morton. They succeeded, but also failed; as they got Morton back, he was shot a second time, and died as they returned. Unfortunately, so did three members of the picket, and Bugler Puna Singh.

With Morton’s death Lloyd found himself the senior military officer and so took command of the defence of the fort, which continued to be besieged for another two weeks, for as late as January 18th Hertz was reporting that the garrison was acting defensively only. The initiative was only regained with the arrival of over one thousand Military Police reinforcements. The numbers proved decisive, and by February 3rd active resistance had been quelled and the Sima camp firmly established. The road builders and tax collectors could now begin.

The three surviving picket members who had attempted to rescue Morton were awarded the Indian Order of Merit, then the highest gallantry award available to native troops – Bugler Singh could not qualify as posthumous awards were not made. Surgeon Lloyd received the Victoria Cross. He went on to become Prinicipal Medical Officer for India, and then South Africa, before becoming Commandant of the Royal Army Medical Corps. Knighted in 1923, he died at St. Leonard’s on the Sussex coast in 1941 in the midst of another, much more complicated, war.

Henry Hertz, born in 1863 in Ribo, Denmark, grandson of a bishop, was educated at St. Xavier’s College in Calcutta. He spent his working life in the Burmese Police, became recognised as an expert in the Kachin language, and died in Burma in 1932.

Boyd Morton’s mother, Helen, probably died in India before the century’s end, and apart from Boyce was the only member of the family to die abroad, despite their long service in India. Father Boyd senior died in Cheltenham (at 2 Priory Parade, part of a splendid still-extant Georgian terrace), a year after Boyd’s sister Lillie. Sister Amy died there in 1932, and brother Robert, a tea-planter, passed away, also in Cheltenham, in 1943. The exception was brother Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Ross Morton, who died at Knightsbridge in Devon in 1938. It was through his daughter, Mabel, that the military connection stretched into the next generation. She married Air-Chief Marshall Sir Roderic Maxwell Hill, C-in-C Fighter Command from 1943 to 1945, a strange contrast to his wife’s uncle dying in a Burmese jungle clearing only fifty years earlier.

Sources

Military

'The Problem of the Kachin Hills' - chapter online at shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in

Genealogy

London Gazette 15th July 1887

ibid., 2nd July 1875

www.findagrave.com

www.ancestry.co.uk

The India List & Indian Office List (India Office, London)

Edinburgh Gazette, 15th March 1870

Military

'The Problem of the Kachin Hills' - chapter online at shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in

Genealogy

London Gazette 15th July 1887

ibid., 2nd July 1875

www.findagrave.com

www.ancestry.co.uk

The India List & Indian Office List (India Office, London)

Edinburgh Gazette, 15th March 1870