HENI TE KIRI KARAMU:

TAURANGA WAR, NEW ZEALAND, 1864

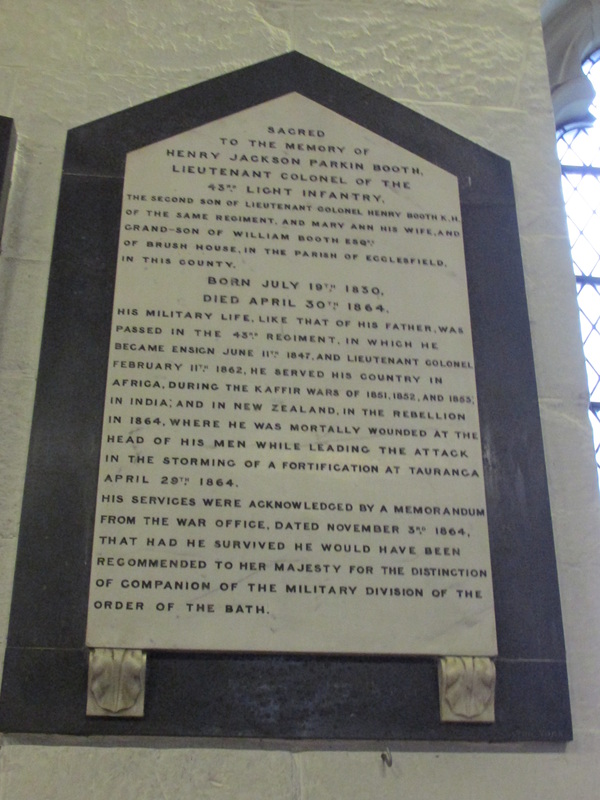

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Jackson Parkin Booth, 43rd Light Infantry

All Saints, Northallerton, Yorkshire

Captain John Fane Charles Hamilton, HMS Esk

Holy Trinity Church, Ryde, Isle of Wight

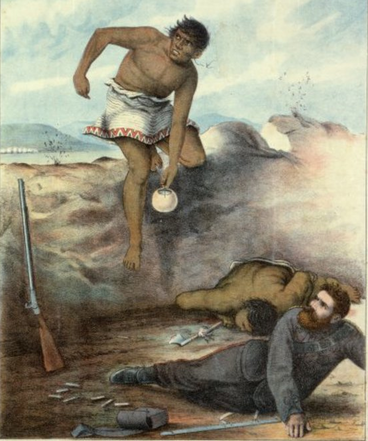

(Wilson & Horton Ltd. Wilson & Horton (Firm) :"For his enemy." - An episode of the Maori War. Wilson & Horton, lith. Auckland, Wilson & Horton, 1895.. Ref: C-034-002-3. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22523898)

A Maori warrior carries water to a wounded British soldier, even though the British are attacking the Maori camp. A dramatic scene, significant to this story because the soldier on the ground is 34 year-old Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Booth, officer commanding the 43rd Light Infantry at what has become known as the Battle of Gate Pa.

The Man

The Booth family of which he was a member came to prominence in the 18th Century as a firm of Rotherham ironfounders, and they soon became an early example of Northern industrialists moving up in the world. The senior partner, John Booth, moved into Brush Hall in Ecclesfield, north of Sheffield (which became Firth Park Grammar School, and is now demolished), while his nephew William was in Mosborough Hall (now a Best Western Hotel) near Rotherham. When John died William inherited Brush Hall and moved there with his wife Sarah to raise his five sons, one of whom, Henry, married Mary Ann Monkhouse, from Romanby near Northallerton, moved to live in that town, and in the course of his military career became Lieutenant-Colonel of the 43rd (Oxford and Buckinghamshire) Light Infantry – the income from his father’s business was clearly large enough to enable him to buy the commission.

He is not our man in the picture, however. That is his second son, born in 1830, christened Henry Jackson Parkin Booth, following Charles in 1828, and followed by William in 1832. As was often the case the three sons, now gentrified, appeared to have scorned the commerce that had made their family fortune. Charles followed the law, and became a barrister, and the other two joined the army; William eventually became a Major-General in the Royal Artillery, while Henry joined his father’s old regiment (Henry senior died in 1841), following in his father’s footsteps by becoming its Lieutenant-Colonel in 1863.

By the time the 43rd were sent to New Zealand in 1863 they, and their recently-appointed commander, were experienced and battle-hardened. In 1851-53 they had been engaged in the Kaffir or Xhosa wars in South Africa, and in 1857-59 they had been heavily involved in the suppression of the Indian Mutiny. Against the Maori they really should have known what they were doing.

The background

The various 19th century New Zealand wars are known collectively to the British as The Maori Wars, but to the Maori they are The Land Wars. The naming of wars is interesting, as the title they are given tends to suggest what the cause is thought to be. The British thought the Maori were the problem, but the Maori think the problem was land, and they are right.

The issue in New Zealand lay, as elsewhere in the world, with the conflict inherent in European settlers appropriating land that native peoples regarded as their own. A series of disputes had blazed over the previous twenty years, and in 1863 another one broke out, in the Waikato region of North Island.

To prevent arms, supplies and reinforcements reaching the Waikato Maori the British attempted to control the sea routes to the area, and in January 1864 that included building a military base at the Te Papa Mission station in the Tauranga region on the island’s east coast. They did not, however, consult Rawiri Puhirake, the chief of the local tribe.

The Action

In March 1864 Rawiri issued a challenge to the British, including rules of engagement, and commenced the building of a pa, or fortified stockade, at a place called Pukahinahina, only 5 miles from the British base, to control access into the region.

Obviously the British could not allow such opposition, and gathered troops. On the 21st April General Sir Duncan Cameron arrived in Tauranga Bay to take overall command of the campaign. In all he had seventeen hundred men: the 43rd under Lieutenant-Colonel Booth; the 68th (Durham) Light Infantry under Lieutenant-Colonel Greer; and six hundred marines and sailors from the ships in the bay (Esk, Curacoa, Harrier, Falcon and Miranda). The number of Maori in the pa has been estimated at around two hundred and fifty (reinforcements expected from Waikato failed to arrive), so it should have been easy.

The engagement has gained the name of Gate Pa from the appearance of the fortification. The raised mound was surrounded by a fence, with a central section that looked like a gate. Cameron sent Freer and the 68th to the rear of the pa, to prevent any escapees, and then at daybreak commenced a bombardment of the wooden fortification, using artillery pieces and gunners from the naval ships.

The bombardment lasted for eight hours, being called off when the pa appeared to have been destroyed. Then Booth went in with three hundred men of his 43rd, aiming for the shattered gate.

Unfortunately for the 43rd the pa was not as it appeared. It looked like a mound with a fence around it, with a gate as an entrance. In fact it was two mounds, divided by a deep ditch or trench which the apparent gate led into. Moreover, the two mounds had been tunnelled by the defenders, and turned into redoubts, providing protection against the bombardment, so the majority of the defenders had escaped the artillery unscathed, and awaited the British charge into the ditch they did not expect to find.

Within ten minutes the attack had failed. Over one hundred troops lay dead, dying or wounded in the ditch. The surviving British pulled back, and overnight the Maori left the pa, leaving twenty-five dead. They were pursued by Greer and the 68th, who prevented them erecting another pa, and defeated them at Tauranga to end the conflict, but Gate Pa was still perceived to be a shattering defeat for the British.

Lieutenant-Colonel Booth had been fatally wounded in the right arm and spine, but before he died told how an English-speaking Maori had given him water as he lay wounded, and thirty years later that was still remembered, and the image printed in an Auckland magazine. The picture shows a male warrior, but the story goes that it was in fact a woman, Heni Te Kiri Karamu, who took water to the wounded and dying who had been abandoned by the retreating troops (and that did not go down well). One only hopes that Greer and his soldiers treated the defeated at Tauranga as nobly and compassionately.

[Captain Hamilton's story will be added later]

Afterwards

And Henry's brothers? Charles eventually died in 1915, having retired to Bournemouth, and William also retired to the south-west, dying at Rose Duryard near Exeter in 1921. Both had sons named Henry.

General Duncan Cameron returned to England and was Governor of the Royal Military College at Sandhurst between 1868 and 1875, He died at Blackheath in 1888, aged eighty, and is buried in Brompton Cemetery.

Hene Te Kiri Keramu became a noted teacher and interpreter. She survived the longest of our main protagonists, dying in 1933, at the age of ninety-three.

A Maori warrior carries water to a wounded British soldier, even though the British are attacking the Maori camp. A dramatic scene, significant to this story because the soldier on the ground is 34 year-old Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Booth, officer commanding the 43rd Light Infantry at what has become known as the Battle of Gate Pa.

The Man

The Booth family of which he was a member came to prominence in the 18th Century as a firm of Rotherham ironfounders, and they soon became an early example of Northern industrialists moving up in the world. The senior partner, John Booth, moved into Brush Hall in Ecclesfield, north of Sheffield (which became Firth Park Grammar School, and is now demolished), while his nephew William was in Mosborough Hall (now a Best Western Hotel) near Rotherham. When John died William inherited Brush Hall and moved there with his wife Sarah to raise his five sons, one of whom, Henry, married Mary Ann Monkhouse, from Romanby near Northallerton, moved to live in that town, and in the course of his military career became Lieutenant-Colonel of the 43rd (Oxford and Buckinghamshire) Light Infantry – the income from his father’s business was clearly large enough to enable him to buy the commission.

He is not our man in the picture, however. That is his second son, born in 1830, christened Henry Jackson Parkin Booth, following Charles in 1828, and followed by William in 1832. As was often the case the three sons, now gentrified, appeared to have scorned the commerce that had made their family fortune. Charles followed the law, and became a barrister, and the other two joined the army; William eventually became a Major-General in the Royal Artillery, while Henry joined his father’s old regiment (Henry senior died in 1841), following in his father’s footsteps by becoming its Lieutenant-Colonel in 1863.

By the time the 43rd were sent to New Zealand in 1863 they, and their recently-appointed commander, were experienced and battle-hardened. In 1851-53 they had been engaged in the Kaffir or Xhosa wars in South Africa, and in 1857-59 they had been heavily involved in the suppression of the Indian Mutiny. Against the Maori they really should have known what they were doing.

The background

The various 19th century New Zealand wars are known collectively to the British as The Maori Wars, but to the Maori they are The Land Wars. The naming of wars is interesting, as the title they are given tends to suggest what the cause is thought to be. The British thought the Maori were the problem, but the Maori think the problem was land, and they are right.

The issue in New Zealand lay, as elsewhere in the world, with the conflict inherent in European settlers appropriating land that native peoples regarded as their own. A series of disputes had blazed over the previous twenty years, and in 1863 another one broke out, in the Waikato region of North Island.

To prevent arms, supplies and reinforcements reaching the Waikato Maori the British attempted to control the sea routes to the area, and in January 1864 that included building a military base at the Te Papa Mission station in the Tauranga region on the island’s east coast. They did not, however, consult Rawiri Puhirake, the chief of the local tribe.

The Action

In March 1864 Rawiri issued a challenge to the British, including rules of engagement, and commenced the building of a pa, or fortified stockade, at a place called Pukahinahina, only 5 miles from the British base, to control access into the region.

Obviously the British could not allow such opposition, and gathered troops. On the 21st April General Sir Duncan Cameron arrived in Tauranga Bay to take overall command of the campaign. In all he had seventeen hundred men: the 43rd under Lieutenant-Colonel Booth; the 68th (Durham) Light Infantry under Lieutenant-Colonel Greer; and six hundred marines and sailors from the ships in the bay (Esk, Curacoa, Harrier, Falcon and Miranda). The number of Maori in the pa has been estimated at around two hundred and fifty (reinforcements expected from Waikato failed to arrive), so it should have been easy.

The engagement has gained the name of Gate Pa from the appearance of the fortification. The raised mound was surrounded by a fence, with a central section that looked like a gate. Cameron sent Freer and the 68th to the rear of the pa, to prevent any escapees, and then at daybreak commenced a bombardment of the wooden fortification, using artillery pieces and gunners from the naval ships.

The bombardment lasted for eight hours, being called off when the pa appeared to have been destroyed. Then Booth went in with three hundred men of his 43rd, aiming for the shattered gate.

Unfortunately for the 43rd the pa was not as it appeared. It looked like a mound with a fence around it, with a gate as an entrance. In fact it was two mounds, divided by a deep ditch or trench which the apparent gate led into. Moreover, the two mounds had been tunnelled by the defenders, and turned into redoubts, providing protection against the bombardment, so the majority of the defenders had escaped the artillery unscathed, and awaited the British charge into the ditch they did not expect to find.

Within ten minutes the attack had failed. Over one hundred troops lay dead, dying or wounded in the ditch. The surviving British pulled back, and overnight the Maori left the pa, leaving twenty-five dead. They were pursued by Greer and the 68th, who prevented them erecting another pa, and defeated them at Tauranga to end the conflict, but Gate Pa was still perceived to be a shattering defeat for the British.

Lieutenant-Colonel Booth had been fatally wounded in the right arm and spine, but before he died told how an English-speaking Maori had given him water as he lay wounded, and thirty years later that was still remembered, and the image printed in an Auckland magazine. The picture shows a male warrior, but the story goes that it was in fact a woman, Heni Te Kiri Karamu, who took water to the wounded and dying who had been abandoned by the retreating troops (and that did not go down well). One only hopes that Greer and his soldiers treated the defeated at Tauranga as nobly and compassionately.

[Captain Hamilton's story will be added later]

Afterwards

And Henry's brothers? Charles eventually died in 1915, having retired to Bournemouth, and William also retired to the south-west, dying at Rose Duryard near Exeter in 1921. Both had sons named Henry.

General Duncan Cameron returned to England and was Governor of the Royal Military College at Sandhurst between 1868 and 1875, He died at Blackheath in 1888, aged eighty, and is buried in Brompton Cemetery.

Hene Te Kiri Keramu became a noted teacher and interpreter. She survived the longest of our main protagonists, dying in 1933, at the age of ninety-three.

COMMENT ON THIS STORY ON FACEBOOK

Sources

Photos

English forces before Gate Pa - Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand (Gate Pa, Pukehinahina ridge, during the New Zealand Wars / Reference Number : PA1-f-046-13-3 /

Display Dates : [ca 1864] / Nicholl, Spencer Perceval Talbot, 1841-1908 Photograph albums)

All Saints, Northallerton - Chrisloader, from Wikimedia Commons

Memorial to Henry Parkin Booth - courtesy of Vince Rutland

Military

http://tauranga.kete.net.nz/battle_of_gate_pa_1864/topics/show/926-henry-jackson-parkin-booth-1830-1864

http://www.lightinfantry.org.uk/regiments/obli/ox_co.htm http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=TH18640507.2.18&l=mi&e=-------10--1----0-all

http://history-nz.org/wars4.html

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/war-in-tauranga/gate-pa

Genealogy

www.ancestry.co.uk

http://www.thepeerage.com

http://firthparkgrammarschool.wordpress.com

© Jonathan Dewhirst 2013